PESSOA: A Biography

PESSOA: A Biography

by Richard Zenith

Liveright. 1,055 pages, $40.

A NEW BIOGRAPHY of Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa (1888–1935) runs over a thousand pages, which sounds extreme. However, explains the author, it is really the biography of multiple figures. Readers of Pessoa’s poetry already know in what sense this is true, but others may not be familiar with the poet who was called “the writer of a hundred selves.”

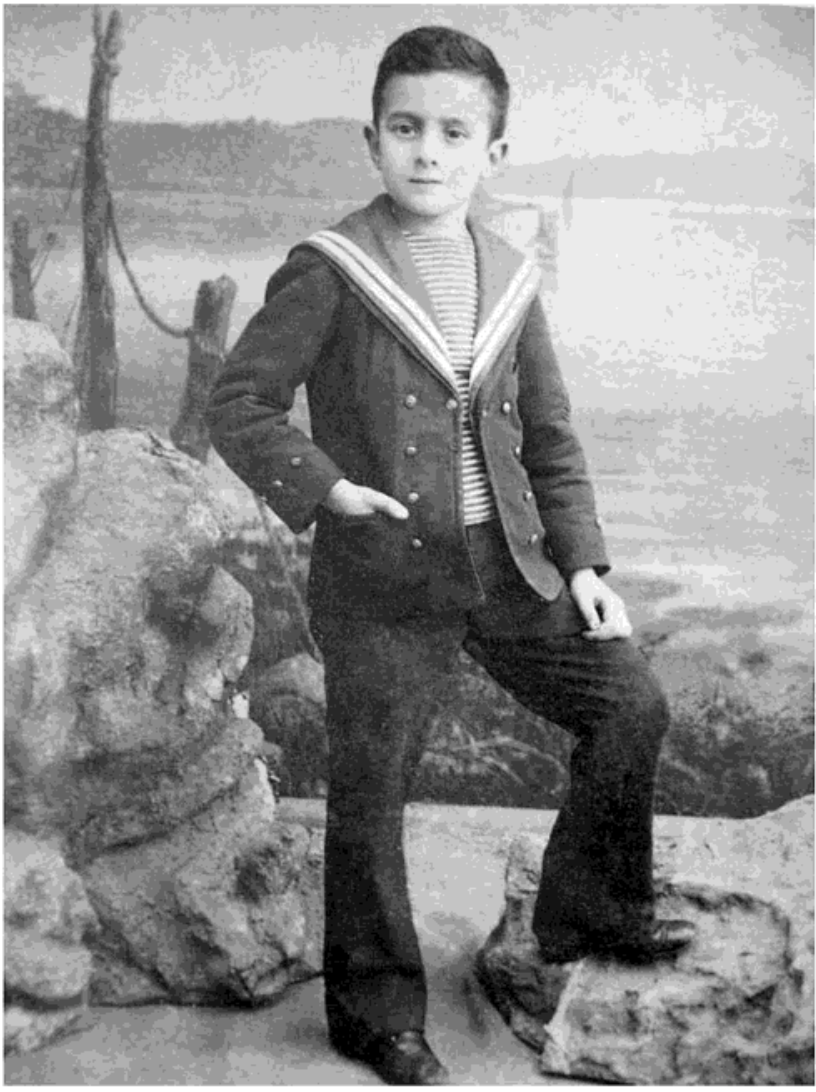

In the opening pages of Richard Zenith’s life of Pessoa, we’re shown an uncaptioned and undated photograph of its subject, whom I would guess to be nine or ten years old. The picture, carefully staged and showing a sweet-faced boy wearing a smart midshipman-style outfit, was taken in 1897, a few years after the boy and his widowed mother had gone to Durban, Natal (the British colony that’s now part of South Africa), where her second husband, formerly a sea captain, had been appointed Portuguese Consul. Nothing in the boy’s appearance suggests that he would grow up to be Portugal’s most acclaimed 20th-century poet. Nor would anyone have predicted that as an adult he would live a life of both whimsy and dejection as an insolvent alcoholic, a man psychologically but not in practice gay, a passionate person who never fell in love, a martyr to art constantly writing but seldom publishing what he wrote under his own name.

The boy’s midshipman’s costume was no doubt a small-scale allusion to Portugal’s history, both glorious and infamous, in maritime exploration and colonization. Figures like Prince Henry the Navigator and Vasco da Gama began sailing to Africa in the 15th century. The story of da Gama’s voyages is the celebratory substance of Os Lusíadas (The Lusiads), the Portuguese national epic, which was written in the 16th century by Luís Vaz de Camões. This astonishing work is regarded as the fountainhead for all subsequent Portuguese literature and can still be sincerely admired so long as we ignore the negative outcomes of those expeditions—colonialism and the slave trade.

The boy’s midshipman’s costume was no doubt a small-scale allusion to Portugal’s history, both glorious and infamous, in maritime exploration and colonization. Figures like Prince Henry the Navigator and Vasco da Gama began sailing to Africa in the 15th century. The story of da Gama’s voyages is the celebratory substance of Os Lusíadas (The Lusiads), the Portuguese national epic, which was written in the 16th century by Luís Vaz de Camões. This astonishing work is regarded as the fountainhead for all subsequent Portuguese literature and can still be sincerely admired so long as we ignore the negative outcomes of those expeditions—colonialism and the slave trade.

Given Africa’s prominence in Portuguese history, Pessoa may have felt it was fully plausible for him to live there. But administration and education in Durban were conducted in English, so the geographical displacement was followed by a linguistic one. Still, the boy became fluent in English and even began composing texts in it; and, because French was part of the curriculum, he soon gained proficiency in that language as well. It was in this period that he began inventing alternate selves: fictional beings who peopled his imaginary universe and manifested their identities by producing letters, stories, and poems. They were forerunners of the fictive authors whose works Pessoa would go on to write and publish under their names rather than his own. He began designating these characters as “heteronyms.” The word was his own coinage, but possibly it was suggested to him by the new adjectives “homosexual” and “heterosexual,” which had only recently come into circulation.

§

If we ask why Pessoa began to invent nonexistent people, several hypotheses come to mind. His father’s death was a shock, made more intense when his younger brother died a few months later. His mother then remarried, bringing a new person into the family, a nucleus soon expanded by five half-siblings. Living in Durban, Pessoa was immersed in English language and culture but was also aware of the city’s large immigrant Indian community and the indigenous Zulu population. How could an intelligent, creative boy not come to see that human possibility was manifold, and to embody that insight in his writings? Expatriation ended in 1905 when he sailed to Lisbon, after which he hardly left the city again. But the seagoing theme reappeared later in the guise of his poems and his only play, The Mariner.

Judging by what he wrote and his bachelor status, Pessoa was most likely a gay man who lived his entire life without having any sexual experience with another person, male or female. “To possess a body is to be banal in the extreme,” he claimed. Meanwhile, his literary self-multiplication can be understood within the framework of queer studies. Some theorists have commented on the mutability of identity in gay people, who grow up without a strong grounding in the “gender binary” and are forced into secrecy and play-acting to conceal their orientation. To suit this intermediate psychology, gay men often attempt to reproduce women’s self-presentation, even if the result is sometimes humorously exaggerated. But then, to avoid exposure (or to attract other men who are excited by masculinity), gay men often fashion a “masculine” persona—again, exaggerated—by adopting macho drag and a tough-guy manner. Many of us will identify with Pessoa’s loneliness as a queer child who was bookish and uninterested in sports. Like most nerds, he ended up without close friends. The solution was to invent his own social circle, an array of articulate personalities always available and interested. One way to do this was to begin an active exchange of letters with many imaginary friends—writing both sides of the correspondence himself.

And then there’s his family name, “Pessoa,” which in Portuguese means “person.” The word is from the Latin persona. Its earliest meaning was “a mask, a false face,” like those covering the heads of actors in Greek and Roman theater. Some dictionaries propose that persona can be traced to Latin personare, which means ”to sound through,” just as actors’ voices had to carry through their masks. Even if this derivation were false, Pessoa might have thought it was accurate. And there were precedents closer to hand. Pessoa knew English poetry very well and would have been aware of Robert Browning’s monologues, which include the famously grim “My Last Duchess.” In “Pauline, the Fragment of a Confession,” the very first poem Browning published, he wrote: “I will tell/ My state as though ‘twere none of mine—despair/ Cannot come near us—this it is, my state.” The implication is that the poet can create fictional people and stage a version of his life through them.

Zenith’s biography does not mention Browning, but it does bring in Wilde’s famous statement from The Critic as Artist: “Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask and he’ll tell you the truth.” Pessoa discovered the works of Wilde in 1907. He endorsed Wilde’s view of the mask, but in reverse. About his characters, he said: “They are beings with a sort-of-life-of-their-own, with feelings I do not have, and opinions I do not accept. While their writings are not mine, they do also happen to be mine.” It’s probable, too, that Pessoa was aware of his slightly older Spanish contemporary Antonio Machado, who developed two poetic alter egos, Juan de Mairena and Abel Martín. Several other poets are noted for their dramatic monologues, pre-eminently Richard Howard, who once acknowledged his debt to Browning with the quote from “Pauline” given above.

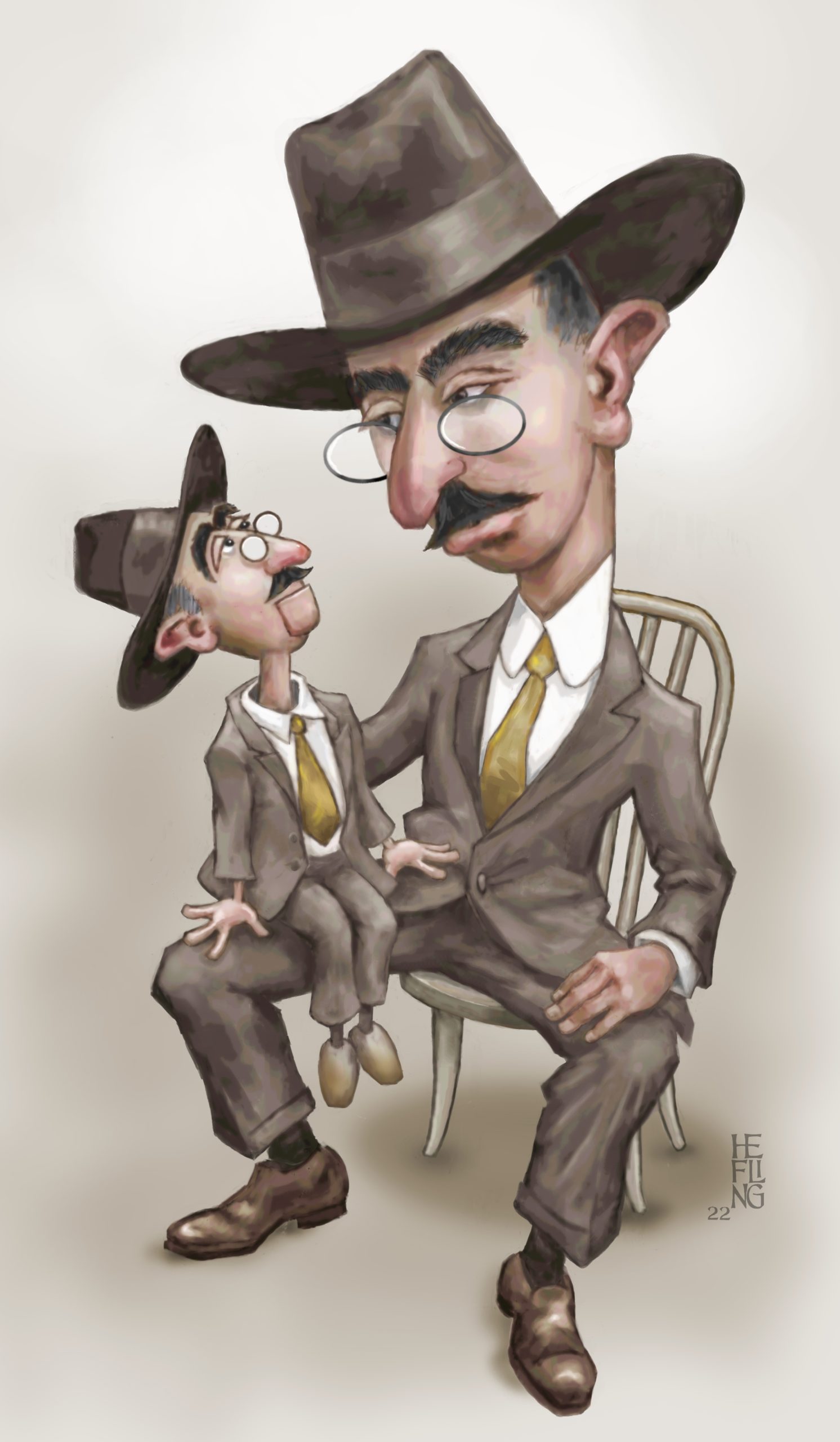

What’s different about Pessoa is how many alter egos he invented, and the fact that he published the poems of his personæ under their names rather than his own. He seems almost to have believed that they existed independently. To back up this belief, he invented brief biographies for them, detailed accounts confirming that these invented personages knew about each other—knew each other as actual, not fictional, people. In a 1935 letter discussing their status, Pessoa offers a typical equivocation: “It has been my tendency to create around me a fictitious world, to surround myself with friends and acquaintances who never existed. (I cannot be sure, of course, if they really never existed, or if it is me who does not exist. In this matter, as in any other, we should not be dogmatic.)” In short, Pessoa promoted his heteronymic creations, but did so with a disclaimer. They helped him feel (if only temporarily) that he existed—because they existed. Even if they produced works that he couldn’t fully endorse, they provided him with a tenuous hold on what Germans call Dasein (existence).

Scholars have catalogued over a hundred Pessoan heteronyms, but the bulk of his published poems are attributed to only three. To the first one, who assumed control of his writing consciousness in 1914, he gave the name Alberto Caeiro. In addition to writing poetry, we’re told that Caeiro was a shepherd, a role that connects him to the pastoral tradition in poetry. This persona quickly produced a spate of poems introducing their author as an anti-metaphysical writer, concerned only with concrete reality and not at all with philosophy. His program leads us to expect a poetry relieved of abstractions, content to record sensory data, perhaps in the manner of the “Imagistes” or Objectivists in English. In fact, only the sketchiest descriptions of things appear in Caeiro’s poems. Instead, he constantly and thoughtfully reiterates his philosophy of not being a thinker or having a philosophy, someone concerned only with the things of this world. Caeiro doesn’t seem to be aware of the paradox, but Pessoa later points it out in the criticism he devised to promote the work of Caeiro. Yes, criticism: pretending to be an outside commenter on his heteronym was one more way to firm up the existence of Caeiro and, for that matter, himself.

Pessoa’s second prominent heteronym is Ricardo Reis, a teacher of Latin somewhere in South America. His concise and chastened output is modeled on the classical poets, especially Horace. Reading them, you get the impression that they are good Portuguese translations of some unknown Latin or Greek author. Many are hortatory, urging the author and his dutiful readers to adopt something like the philosophy of the Stoics when confronting life’s difficulties and disappointments. Reis professes great admiration for Alberto Caeiro, a confirmation of that heteronym’s material existence and artistic value, but one that seems improbable given the incompatibility of their views. Reis’ work is finely composed but seems soberly removed from modern experience and, to that degree, rather bloodless.

Pessoa’s second prominent heteronym is Ricardo Reis, a teacher of Latin somewhere in South America. His concise and chastened output is modeled on the classical poets, especially Horace. Reading them, you get the impression that they are good Portuguese translations of some unknown Latin or Greek author. Many are hortatory, urging the author and his dutiful readers to adopt something like the philosophy of the Stoics when confronting life’s difficulties and disappointments. Reis professes great admiration for Alberto Caeiro, a confirmation of that heteronym’s material existence and artistic value, but one that seems improbable given the incompatibility of their views. Reis’ work is finely composed but seems soberly removed from modern experience and, to that degree, rather bloodless.

The third and most exuberant of the heteronyms is Álvaro de Campos, a cheerful dandy and stroller of the Lisbon streets, volubly celebrating what he sees and knows. His encomiums are directed not just to people and their occupations, but also glorify (as did Marinetti’s Italian Futurism) machines, trains, dynamos, suspension bridges—industrial modernity at large. In his “Triumphal Ode,” he lists all the phenomena, material and otherwise, that he finds wonderful, for example: “the falsely feminine grace of sauntering homosexuals” and “the dazzling beauty of graft and corruption,” as well as “Fraudulent reports in the newspapers.” Whatever exists, all that can be done or thought, inspires his ecstatic approval. This is a turbocharged Whitman who doesn’t care if anyone titters at his trumpeted rhapsodies.

The heteronymic Caeiro and Reis were presented as unmarried, as was the case for Campos, but he at least fantasizes about sexual encounters, some of them not at all heterosexual. In his “Salutation to Walt Whitman” he characterizes his precursor as “Great homosexual who rubs against the diversity of things.” Fair enough, and then, in his “Maritime Ode,” Campos carries Whitman’s “barbaric yawp” much farther than the Kosmos ever did. After an exhaustive catalog of all things nautical and a delirious pæan to the hardy breed of seamen, he turns to pirates, rejoicing in their savagery and carnage. He imagines becoming their “woman” or, more accurately, their masochist slave: “Make me kneel down before you!/ Beat and humiliate me!/ Make me your slave and your plaything!/ And don’t ever deprive me of your contempt!/ O my masters! O my lords!” I wonder how many modern readers find the work of Pessoa’s heteronyms to be fully achieved and persuasive. Portuguese is a mellifluous language, so the poems offer pleasure for the ear, but the content is often didactic in a plodding way, or pumped-up, or even absurd.

§

Pessoa’s heteronymic enterprise is best appreciated as conceptual art—clever, ingenious, even satiric, but not altogether sincere. It’s possible to applaud the multiple-identity brilliance even as we withdraw full assent from its products. The personæ’s bridged distance from the author permits him to evoke them with empathy but also with satirical touches based on exaggeration. When authors record extremes of their thoughts and feelings, they risk being silly or even ludicrous. Attributing one’s personal outliers to a fictional character enables the expression of bizarre psychological states and faulty thinking that are normally concealed to avoid ridicule. Without authorial masks, many ideas that it’s possible for the human mind to entertain would never be recorded.

Pessoa’s masks, made of papier mâché or (sometimes) gold, have a few features in common with his own psychological physiognomy. Through the eyeholes, we can observe his naked gaze, a remarkably attentive gaze, and, for just that reason, wounded. There is no way to understand Pessoa except as a consciousness in torment, if we take seriously statements such as: “I want what I don’t want and renounce what I don’t have. I can’t be nothing nor be everything; I’m the bridge between what I don’t have and what I don’t want.” These negations recall the apophatic method of theology, which arrives at the essence of divinity by listing all the things God is not. Tying himself in these medusan knots, Pessoa manages to convey his own self-contradictory being and its readiness to become nonbeing.

Pessoa did of course publish some works under his own name: poems that are well-wrought and moving. (I’m not referring to those written in English, which, though sincere, are awkwardly expressed in an archaic, often Shakespearean, diction.) For me, his best work is not his poetry but a prose fiction he titled The Book of Disquiet. It was begun as a heteronymic work ostensibly written by a rather colorless figure named Alberto Guedes, but eventually Guedes is replaced by an accountant named Bernardo Soares, who, apart from Pessoan concerns like dreams, illusion, and nonexistence, records his impressions of daily life in Lisbon. The work was written (haphazardly, over a period of many years) by dashing off passages of uncanny observations and reflections. Pessoa never bothered to assemble these passages into any coherent order or to get them into print. The work reaches today’s public as partly the work of various editors. It doesn’t matter which version is read, because the strength of the book resides more in its individual pages than in plot sequence or character development. We might even apply to it this recommendation from Pessoa himself: “Never read a book to the end, nor even in sequence and without skipping.” The randomness of its composition is an analogue for the author’s many struggles with the concept of authentic existence.

The philosophical perspectives outlined by Pessoa are so divergent, so multiple, that as we try to understand his work we find ourselves confronted with a ship built entirely of gangplanks. There are so many ways to clamber aboard that we are stopped short, stymied, no matter how eager we are to accompany its enigmatic captain in his exploration of human nature’s uncharted seas.

Alfred Corn is the author of eleven books of poems, two novels, and three collections of essays. His new version of Rilke’s Duino Elegies was published last year by Norton.