ONE of the many consequences of the fall of Rome and the rise of Christian civilization was that the depiction of the nude human body became taboo, as did virtually all expressions of sexual desire, especially same-sex desire. Artists found various ways to circumvent these prohibitions, including gay artists, who had to choose between complete secrecy and finding a way to sublimate their homoerotic desires in socially permissible ways.

One of the most popular strategies for expressing, and disguising, their passion for the male body was to create images of healthy, virile young bathers in everyday, wholesome settings. This ruse allowed artists from every century to get around taboos on nudity in a way that was understood by the cognoscenti but not by the enforcers of strict moral codes. An article in these pages titled “The Great Cover-Up” (Nov.-Dec. 2019) showed that public bathing in the nude was a common practice for men going back to the Middle Ages, as revealed in artwork from various eras.

The annals of artists who “bathed the gay away” in their paintings of bathers include four landmark works that are discussed in this essay, two pairs of paintings separated by a span of 350 years, all connected by their use of the bathing trope as an acceptable means to convey their homoerotic feelings. It can probably be assumed that all four artists had sexual relations with men. We can apply the label “homosexual” to them, recognizing that this is a relatively recent term, or we might use today’s word “queer,” which can include anyone not conforming to the sex or gender norms of their society.

§

Emerging from the strictures of medieval Christianity, some Renaissance artists found ways to circumvent these constraints by turning to classical and secular themes of mythology and everyday life. Michelangelo (1475–1564) used every trick in the book to justify his passion for the male physique in his art. Indeed he struggled with a lifelong conflict between a deep religious faith and an unbridled attraction to men. He accepted the Sistine Chapel commission to have his soul saved by the Church, but he couldn’t resist expressing his true desires in his work.

Days before the unveiling of his history-changing sculpture of David (1504), the 29-year-old Michelangelo was chosen to paint an image of The Battle of Cascina on a wall of the Palazzo de la Signoria in Florence. This battle was fought between Florence and Pisa on a scorching July day in 1364. Instead of showing a traditional, heroic image of Florence’s triumph, Michelangelo depicted the moment when eighteen Florentine soldiers were caught by surprise while cooling off naked in the Arno River. This choice allowed him to depict his two favorite subjects: the muscular nude male figure and occasions for male bonding.

Michelangelo’s homosocial scene mirrors the environment in which it would be displayed, the Great Council Hall, where only men were allowed. In his creation, Michelangelo shrewdly connected ideas of virility, patriotism, and virtue, represented by his idealized male bodies arranged in a way that allowed the viewer to stare freely at these naked soldiers without fear of disapprobation.

This project brought Michelangelo face-to-face with his rival Leonardo Da Vinci (1452–1519), who was to paint another battle scene in the same room. Leonardo, who wrote unabashedly in his diaries that he “went to the bath houses to see naked men,” criticized the younger artist for “drawing nudes without grace, with a sack of walnuts for muscles.” Neither artist finished his project. With the return of the Medicis to power, the battle subjects, which were conceived to glorify the Florentine Republic, lost their purpose as propaganda.

Michelangelo did finish many studies and a full-sized drawing titled The Battle of Cascina, which we only know from copies. According to legend, the original disappeared after being cut in pieces by a contemporary artist who also specialized in erotic male imagery, Baccio Bandinelli, who was jealous of Michelangelo and aligned himself with Leonardo. Nevertheless, the torn pieces, which seem to have been distributed among various artists, made such a splash that they were used as study material for years to come, becoming, in art historian Michael Rocke’s words, “the fountain source for all painters who picked up a brush thereafter.” The physicality and overt eroticism in the Master’s drawing provided an alibi for the portrayal of sexy male bathers for hundreds of subsequent artists.

§

A prominent example of this is The Bathers at San Niccolò (1600) by Domenico Cresti (1559–1638). This stunning and monumental (56” x 71”) painting shows dozens of young men skinny-dipping and frolicking in Florence’s Arno River, one of the city’s favorite areas for same-sex encounters at that time. The focal point is a male couple locked in an ardent gaze, their hands touching, in the foreground. The sitting man points toward a bathhouse with towels hanging, where perhaps they will go after the swim. Next to the bathhouse is the Porta San Niccoló, erected in 1324, which still stands today. This painting shows an idealized vision of friendship and possibly love, while demonstrating a deep admiration for the beauty of the male body. A number of studies have been found, suggesting that Cresti captured these images from his daily life.

To put this elaborate scene in context, it helps to know that Florentine men rarely married before they were thirty. But given that males reach sexual maturity at around the age of fourteen, a lot of them resorted to same-sex relations, to the point that homosexuality was widely known as “the Florentine vice.” It was so widespread that the city established an organization called the Office of the Night, which placed boxes in churches inviting citizens to denounce anonymously any local male who was engaging in “sodomy.” In his book Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence, Michael Rocke estimates that, in a city of about 40,000 people, as many as 17,000 were incriminated at least once, and the sodomy court’s records include virtually every important Florentine family. It seems that in this age of fierce competition among the ruling families, this accusation provided a golden opportunity to bring a rival down a notch.

What’s extraordinary is that Cresti didn’t use a religious or mythological excuse to portray his male nudes. Instead, his pretext was that the painting was inspired by The Battle of Cascina. The central man pointing upward echoes one of the men in Michelangelo’s drawing. His rippled back is a replica of the classical Belvedere Torso sculpture, adding a layer of classicism as an additional appeal to legitimacy. The painting’s scale proves that it was a significant commission. When it recently sold at auction for $732,500, it was described as “the most important example of homoerotic art of the period.”

§

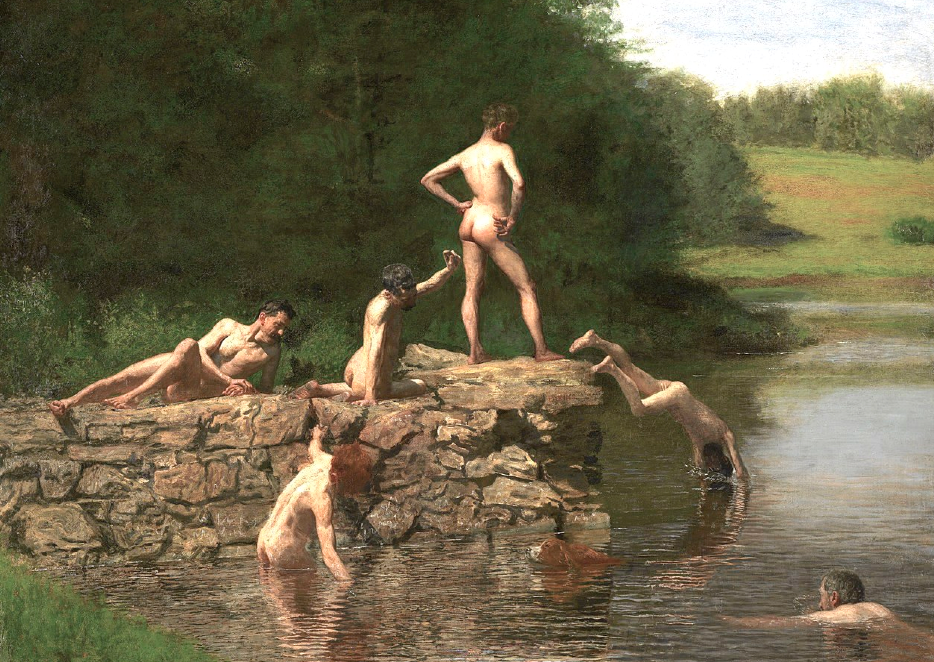

Flash forward 300 years and a direct through-line can be drawn from Cresti’s painting and 1885’s The Swimming Hole, by Thomas Eakins (1844–1916), which portrays five young, naked men in close proximity, while an older man swims toward them with his dog. A crucial commission for Eakins and now one of America’s most beloved paintings, it is universally recognized as a visual poem to male youth. But beneath this bucolic image runs a homoerotic undercurrent that was hitherto unknown in American art. Eakins engaged several of his students to pose nude outdoors in keeping with classical ideas of fitness and comradeship from the Greek gymnasium. To disarm any would-be critics, Eakins loaded his painting with classical references designed to cover its transgressions with a patina of respectability. The pose of the standing youth at the top mimics Donatello’s iconic sculpture David (circa 1440), and the model on the left is posing like the Hellenistic statue The Dying Gaul.

Despite the camouflage, the patron who commissioned the painting was shocked when he received it and politely sent it back, requesting “a painting that he could donate to an art museum someday.” Eakins had broken too many conventions. Instead of creating an Arcadian image of a faraway time and land, he displayed male nudity with no narrative justification, and he used identifiable young men in a recognizable local setting.

There was another explosive reason for the rejection. The Swimming Hole is a thinly-veiled tribute to a poem about loving young males by Walt Whitman, who invented a coded language to express erotic intimacy between men, talking about “threads of many friendships, fond and loving, pure and sweet, strong and lifelong, carried to degrees hitherto unknown.” Whitman envisioned a future in which love between men would be invincible, not invisible, a love that would become the glue that would keep America intact during the Civil War. In Song of Myself, included in the first edition of Leaves of Grass (1855), Whitman describes a bathing scene:

Twenty-eight young men bathe by the shore,

Twenty-eight young men and all so friendly…

Dancing and laughing along the beach came the twenty-ninth

bather…

The beards of the young men glisten’d with wet, it ran from

their long hair,

Little streams pass’d all over their bodies.

Look carefully and you’ll find how Eakins painted himself in The Swimming Hole as “the twenty-ninth bather,” swimming toward the young men. From then on, colleagues referred to Eakins and his male students as “Whitman fellows.” This was the first of several scandals that ended with Eakins getting expelled from the Pennsylvania Academy. Another had occurred when he removed the loincloth from a male model in a class in which female students were present.

Eakins’ sexuality is still being debated, with major scholars remaining silent on the matter. But no one can deny that Eakins hated the prudish Victorian standards and the flattering portraits that were the trademark of artists such as John Singer Sargent. His obsession was with capturing the human body in all its truth and glory. He wrote to his parents: “A female body is the most beautiful thing in the world, except for a naked man.”

Eakins took many photographs of male nudes, including a series of an old man who appears to be Whitman. These photos justified his questionable outdoor trips “to see how sunlight bleached out the unclothed bodies.” His major paintings feature sexually charged images of rowers, wrestlers, and, in Salutat (1898), a boxer, not in action but as the passive object of desire of the male crowd, with his buttocks as the centerpiece.

At age forty, Eakins married Susan Macdowell. In a portrait he did of her during their childless marriage, Eakins’ dog, the one featured in The Swimming Hole, is portrayed with more warmth than is his wife. His dashing studio partner and constant companion was the sculptor Samuel Murray (1869–1941), who was 25 years younger than Eakins. This was by all accounts the most important relationship in Eakins’ life. The two men went on extended camping trips, took frontal nude photos of each other, and forged a close friendship with Walt Whitman, whose subversive work was rejected during his lifetime, as was Eakins’.

§

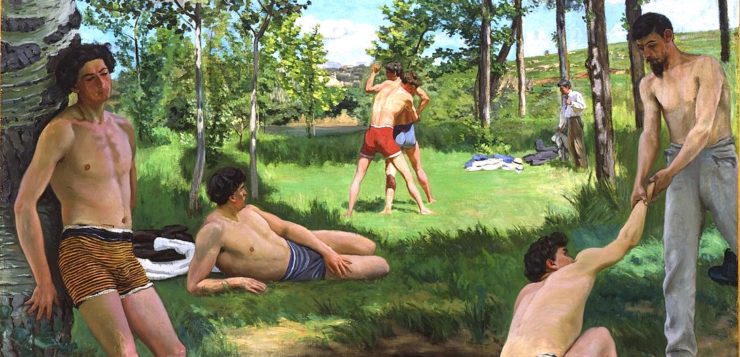

An important inspiration for Eakins’ work was actually a painting from a few years earlier, Summer Scene (1869), by Frédéric Bazille, which Eakins saw at the 1870 Paris Salon. A member of the circle of young Impressionists that included Monet and Renoir, Bazille created this titillating scene of male bathers a year before his death. Summer Scene was the first major painting in centuries to showcase nearly nude male bodies in a contemporary setting. Paintings of frolicking naked women were a staple of the French Salons, while images of naked men in casual settings were nonexistent.

Summer Scene depicts eight young men in different stages of undress enjoying a leisurely day at the Lez River near his hometown of Montpellier, France. Like many artists before him, Bazille covered his large and sensual painting with codes to cloak its affronting homoeroticism. The man leaning against the tree poses like a popular Saint Sebastian by Jacopo Bassano. Next to him, a man who’s looking at another man undressing poses like an odalisque. A shirtless man helping another one to get out of the water evokes traditional images of Christ helping the damned out of purgatory. In the back we see two wrestlers, another popular trope used by artists to legitimize same-sex desire.

His provocative Fisherman with a Net (1868), which included a male nude from behind, was rejected by the Salon the year before. This is probably why Bazille, who initially sketched all the men in Summer Scene to be nude, ended up adding swimming trunks. Despite this cover-up, his mixture of classicism and modernity was too audacious for the general public. When he exhibited it at the Paris Salon, many viewers were shocked and amused, and the press spoofed it with disparaging caricatures. One latter-day critic referred to it as “an ode to homoerotic hedonism” and “a personal fantasy purporting to be external fact.”

Bazille was a member of a prominent family and also a presence in Paris’ homosocial society. He avoided marriage under the excuse “of an early heartbreak with a woman.” When asked about why he painted nude men, his response was that “females were horribly difficult to paint.” He created several loving portraits of his intimate friend Edmond Maître, a dandy like himself, with whom he spent most of his spare time, playing piano for four hands until dawn.

A sign that Bazille may have been tormented by his sexuality is that he was prone to melancholy and complained about “having constant migraines while he was painting his nude men.” It has also been suggested that he enlisted in the Franco-Prussian War—which he could have avoided since his father had paid for a substitute—as a way to escape his sexual urges.

Maître, who had begged Bazille not to go to war, was devastated by Bazille’s death in battle at age 28, the year that Summer Scene debuted. In a letter, Maître said: “I have lost half of myself; he was the most lovable of all young men. No one will ever fill the empty place he leaves in my soul.” Because of Bazille’s short life and career, we can only surmise how far he might have taken his queerness in his work.

§

Postscript: The use of bathers as a façade was shattered by the openly gay artist Paul Cadmus (1904–1999), who portrayed a matter-of-fact scene of gay domesticity in his groundbreaking painting The Bath (1951), which, after years of being in storage, is finally displayed at the Whitney Museum. The lineage of bathers’ images culminates in the openly erotic, sun-drenched swimming pools of David Hockney (b. 1937), the first Western artist to use his work to come out. A packed room in a recent New York auction broke into applause when his Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) (1972) sold for over $90 million, a record for a living artist. I’d like to believe they were also applauding the end of centuries of repression and the unfettered embrace of openly queer bathers in art.

Ignacio Darnaude is an art historian and film producer. He is currently developing the docuseries Hiding in Plain Sight—Breaking the Queer Code in Art.

Discussion1 Comment

Great article Ignacio!!