SOMETIMES YOU HAVE TO LIE

SOMETIMES YOU HAVE TO LIE

The Life and Times of Louise Fitzhugh,

Renegade Author of Harriet the Spy

by Leslie Brody

Seal Press. 335 pages, $30.

BEST KNOWN for her novel Harriet the Spy (1964), Louise Fitzhugh (1928–1974) was a lesbian writer who worked at a time when LGBT people were stereotyped as criminals and corrupters of youth. For this reason, she had to maintain a low profile to get her work published, especially because she wrote novels for children and young adults.

A new biography by Leslie Brody, Sometimes You Have to Lie, is an exploration of Fitzhugh’s life in its social and historical context. One of Brody’s projects is to reveal the central conflicts in the life and fiction of her subject, who struggled with truth and falsehood, coming out versus staying in the closet, committing to work versus relationships, and other either/or dualities that arose in the course of her short life.

Born in Memphis in 1928, her family was wealthy and eccentric. She had an uncle who lived in his parent’s attic and whose primary occupation appeared to be spending time with paper dolls. Her father, Millsaps Fitzhugh, was a lawyer, and her mother, Mary Louise Perkins, was a former ballet teacher. They went through a horrible divorce in which her father retained custody of Louise, who was told that her mother had died. Years later, she discovered that this was a lie and that her mother was very much alive. This discovery formed the psychological backdrop for her relentless pursuit of truth, whatever the cost.

She left home and attended Bard College in upstate New York, and also took lessons at the Art Students League in New York City, as she aspired to be a painter. While at Bard, she studied writing with the gay poet James Merrill, with whom she remained lifelong friends. In the City she found her way to Greenwich Village, where she attended gatherings with other lesbian artists and writers, including the pulp fiction writer, Marijane Meaker (aka M. E. Kerr, among other pennames), photographer Gina Jackson, and playwright Lorraine Hansberry. In 1961, she collaborated with Sandra Scoppettone on the story Suzuki Beane, a spoof of the children’s book Eloise. During this time, she came into her own, went to gay bars, and swore off dresses, instead donning trousers and her signature cape. Brody discusses the creative conflicts and difficulties that Fitzhugh encountered throughout her career. She wanted to be recognized as a painter, but did not find validation in this pursuit. This was a time when male artists were center stage and there was little room for women, much less lesbian, artists. She did not take her writing as seriously as her art and was conflicted, at times quite lost, about her creative work. She suffered from bouts of depression and resorted to drugs and drinking. After many fits and starts, she managed to write the children’s novel, Harriet the Spy. The story revolves around Harriet, eleven years old, who lives in Manhattan’s Upper East Side and aspires to be a writer. She’s encouraged in her efforts by her nanny, “Ole Golly.” Harriet has a notebook in which she writes her perceptions of people and places in her neighborhood. She avoids doing “girlie things,” wearing jeans and a sweatshirt and carrying a flashlight and sneakers. She has two friends who are also nonconforming: Janie wants to be a scientist, and Sport takes care of his writer father and wants to be a CPA. Harriet gets into trouble when the other kids, including her friends Janie and Sport, get hold of her notebook and read what she wrote about them. She loses her friends and is horribly bullied, and doesn’t understand what all the fury is about, as she was only speaking her truth. She becomes increasingly withdrawn. Her former nanny (Ole Golly) is summoned and offers this bit of advice: “Sometimes you have to lie.” In time, Harriet makes amends, wins back her friends, and becomes editor of the class paper. In many ways Harriet The Spy is reminiscent of other coming-of-age stories of the postwar era that deal with young people confronting the hypocrisy of the adult world. Examples would include Salinger’s Catcher In The Rye (1951), Carson McCullers’ The Member of the Wedding (1946), and Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960). Holden Caulfield, Frankie, and Scout are all attempting to discover where they belong in this world, and to understand what’s lost when they succumb to its demands. Similarly, Harriet’s life lesson is about how much truth can be told before one is exiled from the group. She’s finding her way through this complicated challenge: how to remain true to herself while in harmony with others. The wisdom of Ole Golly was recognized long ago by Emily Dickinson (in Poem #1129): “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant.” In Harriet the Spy, Fitzhugh brilliantly portrayed the struggle we all face concerning maintaining our individuality while wanting to belong to a group. For Fitzhugh, this struggle played out within the context of truth and lies. Given her family’s aversion to the truth, she learned early on to tread carefully with what is revealed and what is hidden. All this was compounded by her position as a woman and a lesbian during the repressive pre-feminist, pre-Stonewall years. Brody has written a fascinating and insightful biography of a complex and fascinating personality who has inspired many living writers, including Alison Bechdel (Fun Home). Harriet the Spy ranks #12 on the Fifty Best Children’s Books list. A film adaptation was made in 1996 and a TV version in 2010, and Apple TV is planning an animated version with Jane Lynch as Ole Golly.

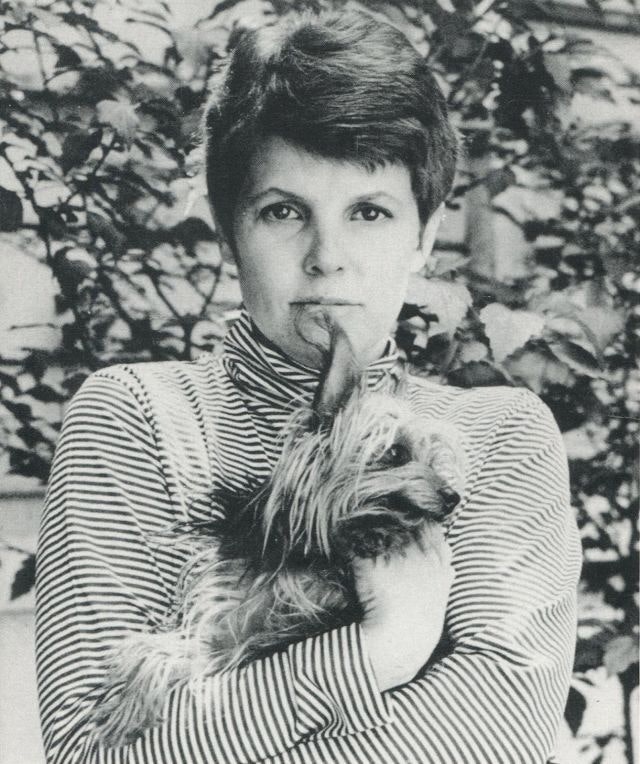

Image via Twayne United Authors Series.

Irene Javors, a frequent contributor to this magazine, is a psychotherapist based in New York City.