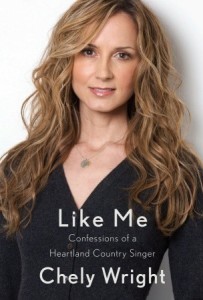

Like Me: Confessions of a Heartland Country Singer

Like Me: Confessions of a Heartland Country Singer

by Chely Wright

Pantheon Books. 286 pages, $25.95

UNLESS YOU SPENT the spring and summer in a monastery, you will have heard the news that country singer Chely Wright broke new ground in that historically conservative world by coming out as a lesbian. Sure, k. d. lang got her start in country music, but she’s Canadian and was never embraced by American country radio, which is why she ultimately eschewed the twang and kept the torch songs in her repertoire. Wright is different. She worked her way from minuscule gigs in nursing homes to the top of the Billboard country charts, from various poor but cozy family homes in Wellsville, Kansas, to world travel, wealth, fame, and success as a country singer, all the while guarding the secret that would define, and nearly end, her life.