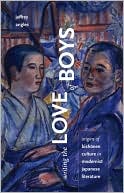

Writing the Love of Boys: Origins of Bishonen Culture in Modernist Japanese Literature

Writing the Love of Boys: Origins of Bishonen Culture in Modernist Japanese Literature

by Jeffrey Angles

University of Minnesota Press. 302 pages, $25.

IN THIS relatively short study, Jeffrey Angles explores the theme of love between men and boys in the literature of Japan’s modernist period, concentrating on three writers from this period: the poet, short story writer, and painter Murayama Kaita (1896–1919); the detective novelist and essayist Edogawa Ranpo (1894–1963); and the avant-garde prose writer Inagaki Taruho (1900–1977).

Aided by his detailed knowledge of the language and of Japan’s cultural history, Angles offers close readings of Kaita, Ranpo, and Taruho’s works. There is some obligatory hat tipping to queer theory and recent research on this subject. He places the three writers in the context both of Japanese literary history and the world stage. This was the period, after all, that saw the birth of psychoanalysis and major advances in transportation and technology, developments that inspired both wonder and unease. Psychoanalysis, in particular, provided a new vocabulary for talking about human sexuality.

Angles has a lot of ground to cover, and he does so succinctly, providing a useful summary of the social, political, and cultural world events that influenced Japan’s Taishō and Shōwa periods. He avoids delving deeply into the biographies of the three writers but does focus on how their friendships with each other, and with other writers of the time, created a kind of community of difference. They explored, and sometimes championed, the cause of same-sex love, in particular the love between boys and young men. They formed discussion groups and collaborated on projects, one of which was to collect, catalog, and anthologize same-sex-themed writing from world history.

Angles is careful to establish that the Japanese modernists were not necessarily “homosexual” in our modern sense. The idea of a same-sex orientation didn’t really take shape in Japan until the 1920’s. Kaita, Ranpo, and Taruho all had relationships with women, though one suspects that this was motivated by societal pressure rather than genuine sexual attraction. And for all of their public interest in “the love of boys,” the writers either denied ever actually engaging in sex with young men or were artfully ambiguous about it in their own writings. Ranpo, in particular, wrote extensively, in essays as well as fiction, about the subject of same-sex love as a topic of research, and even flirted with a full-on confession in certain autobiographical writings. Still, he never identified as a dōseiai—someone who identifies as same-sex oriented.

In addition to its specific and detailed exploration of same-sex themes in popular writing at a pivotal period in Japanese literary history, Writing the Love of Boys also provides fascinating details about the larger cultural transformations of Japan in the 1920’s and 30’s. For example, most of the writers at this time made a living by selling stories and serialized novels to popular, cheaply printed magazines—and it’s astonishing to read that in 1932 there were 11,118 different magazines being published in Japan. He also provides intriguing descriptions of urban life in Japan in the 20’s and 30’s, and of the complicated cultural milieu of wartime and post-war Japan. It was during this latter period that Ranpo and especially Taruho both enjoyed a revival of sorts. Of the three, Taruho seems the most heroic, not only for his bold sense of artistic exploration, but for his even bolder, unapologetic stance on sexuality. To the end of his life, he championed the love of boys as a force that made unique and valuable contributions to Japanese culture.

Angles’ study is tightly focused in its scope and subject matter. The book will certainly be of interest to specialists and scholars, but it’s a useful study for anyone interested in Japanese literature in general and the modernist period in particular. Angles successfully establishes the wide-ranging influence that three writers had beyond their own generation, and he paints a vivid picture of the vibrant and exciting cross-cultural flow of ideas and artistic experimentation in the first few decades of the last century.

________________________________________________________

Jim Nawrocki is a freelance writer based in San Francisco.