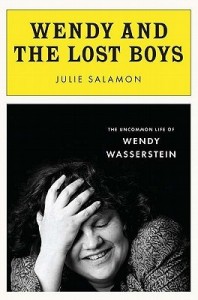

Wendy and the Lost Boys: The Uncommon Life of Wendy Wasserstein

Wendy and the Lost Boys: The Uncommon Life of Wendy Wasserstein

by Julie Salamon

Penguin. 460 pages, $29.95

ONE OF THE IRONIES of the life of Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright and fag hag extraordinaire Wendy Wasserstein is that after years of struggling to make Stephen McCauley’s 1987 novel, The Object of My Affection, into a movie, producers insisted that she alter the ending to show all of the characters coexisting happily and interacting productively. The novel considers what happens when a straight woman and her gay roommate/best friend decide to have a baby together. Wasserstein was attracted to the property because, unsuccessful in her relationships with heterosexual men yet desiring to have a child, she had struggled to conceive through in vitro fertilization with gay set and costume designer William Ivey Long, and may have even proposed creating a family with gay playwright Terrence McNally, with whom she possibly had an affair in the late 1980’s—while he was between husbands and just as the film of McCauley’s novel was going into production.

The power of McCauley’s conclusion lies in its absence of resolution. Julie Salamon’s biography of Wasserstein reveals the playwright’s unhappiness with the lack of resolution in her own life, coupled with her paradoxical refusal to make the compromises without which any such resolution would be impossible. In part, this was a reaction against her upbringing, for the Wasserstein family was extraordinarily private and maintained a placid surface existence by ignoring troubling realities. Wendy was shocked to learn as a young adult that her two older siblings were actually her mother’s children from an earlier marriage to the brother of Wendy’s own father, whom Mrs. Wasserstein had married after the death of her first husband. Wendy was a successful playwright in her forties before she met the developmentally disabled older brother to whom her parents had never referred after confining him to an institution. Wendy’s own obsession with secrecy helped to create—and to forestall the resolution of—the painful ambivalence that dominated her own life. Individual friends were told only portions of her story and then kept apart lest they pool their information.

The portrait of Wasserstein that emerges from this biography is one of a warm, witty, delightful companion who exacted the strictest loyalty from her friends but had no compunction about exploiting them when doing so was to her advantage. In college, Wendy was the supportive friend who stayed up late with female classmates listening sympathetically to the details of their sexual and romantic crises and discussing their frustrations as women in a changing world. Yet those same trusting friends were shocked to find their most intimate secrets revealed, sometimes verbatim, onstage in Uncommon Women and Others (1977) and The Heidi Chronicles (1989). For Wasserstein possessed not only a great ear for vernacular rhythms but also, apparently, total recall of conversations.

She could be even more exploitative in her treatment of her gay male friends, those “lost boys” to which Salamon’s title condescendingly refers (from J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan), as if to suggest that Wasserstein was able to mature emotionally when the numerous gay “objects of her affection” could not. For all of her adult life, Wasserstein seems to have preferred the company of gay men, with whom she could nest emotionally and creatively without having to lie in bed “pretending this is wonderful” as they “sweat and push” on top of her (or so she describes heterosexual coitus in Uncommon Women).

Beginning in graduate school, Wasserstein delighted particularly in the gay men whom she met in the theatre. Playwrights Charles Durang and Albert Innaurato—along with scene and costume designer William Ivey Long—were her classmates at the Yale Drama School (where she also made friends with fellow student Meryl Streep, who would appear in an early Wasserstein stage play). Durang would become the first of the gay men to be known as her “husbands”— the men with whom she would speak on the telephone multiple times a day, with whom she would both spend holidays and collaborate professionally. Later “husbands” included songwriter William Finn (Falsettos), director Gerry Gutierrez, and theatre company creative director André Bishop (Playwrights Horizon, Lincoln Center). The pattern developed with Durang would repeat itself until Wasserstein’s death: while she expected her “husband” to support her as she went through disappointing heterosexual relationships, she would cut him out of her life when he found a (male) lover. Wasserstein was fundamentally unable to share her “husbands” with their husbands.

Wasserstein’s most dysfunctional relationship was with William Ivey Long, her classmate in graduate school, who, like Wasserstein herself, would go on to enjoy a highly successful career in the theatre, winning four Tony Awards, including for The Producers (2001) and Hairspray (2003). When both were in their forties, Long agreed to pay for half of Wasserstein’s fertility treatments and to supply the sperm as she attempted to become pregnant. He remained by her side and spent tens of thousands of dollars, only to be dismissed when Wasserstein found an alternative way of conceiving the child, which would end up being born three months prematurely, weighing only one pound, twelve ounces, paternity undisclosed.

Wasserstein’s life and plays offer fascinating psychological territory to be explored, but Salamon is not equal to the task. While she recognizes the contradictions in Wasserstein’s life, she resists exploring their source. It’s as though whenever she comes upon a fissure that indicates seismic activity below, she steps gingerly around it or simply ignores it. Some of these contradictions are minor, such as Wasserstein’s inability to arrive on time to professional meetings but her quickness to anger when someone kept her waiting. More glaringly, Salamon never considers why a heterosexual woman turned to one gay man after another for emotional intimacy, yet invariably felt betrayed when one by one they entered a lasting relationship with another man. Wasserstein was far too intelligent not to recognize this pattern herself, yet Salamon never wonders why Wasserstein kept repeating it, over and over. Likewise, Salamon acknowledges but never explores the paradox of Wasserstein’s enjoining her closest friends to keep the secrets that she herself blithely revealed to others.

In addition to its intellectual complacency, this is ultimately a disturbingly unreliable biography of Wasserstein because it is largely undocumented. In a secrecy-generating maneuver worthy of Wasserstein herself, Salamon cavalierly states in her acknowledgments that “I won’t list every person I talked to for this biography … because I worry about omitting someone from a list that appears all-inclusive.” So she provides no list at all. The result is that the source of many of Salamon’s quotations and much of her information is undocumented, and the critical reader is left to ponder the authority of Salamon’s claims concerning Wasserstein’s inner and private lives.

Perhaps the book’s most shocking revelation concerns a sexual affair that Wasserstein supposedly conducted with playwright Terrence McNally (The Ritz, Master Class, Love! Valour! Compassion!, Some Men) in the late 1980’s. Salamon refers to the affair as an “open secret” among Wasserstein’s friends, yet offers no information about how the affair began, and even less insight into how it was conducted. And even though her break-up pattern is well-established at this point, Salamon blames McNally for this break-up, suggesting that he used Wasserstein to escape the AIDS epidemic that was raging at the time. Salamon even refers in passing to unidentified “friends” who opined that McNally fathered Wasserstein’s child.

Salamon seems to know so little about Wasserstein’s relationship with McNally that she doesn’t even mention Sam Found Out, or The Queen of Mababawe, the teleplay that the two wrote for Liza Minnelli and Lou Gossett, Jr., that aired on May 31, 1988, or “Paying Up,” the never-produced film script on which McNally and Wasserstein collaborated in 1993. Clearly, Wasserstein and McNally had a professional relationship that began well before their sexual affair began in Salamon’s account, and continued for several years after their breakup. The teleplay resonates far more strongly with Wasserstein’s rueful romanticism than with McNally’s sardonic lyricism of the period, suggesting that the script reveals more about Wasserstein’s romantic yearnings than McNally’s. Such information would necessarily color a critical reader’s understanding of their relationship, yet there is no evidence that Salamon interviewed McNally for the biography.

Ultimately, Salamon offers a thin narrative of Wasserstein’s relationships with the gay men that Salamon labels as “lost boys,” even though Wasserstein referred to them as “husbands”—who did in fact support her through her various crises. Both Wasserstein and her gay theatre friends deserve much better than what Salamon has supplied.

Raymond-Jean Frontain has published a chronology of playwright Terrence McNally’s published and unpublished plays, and is currently preparing an edition of McNally’s occasional essays.