DECADENT WOMEN

DECADENT WOMEN

Yellow Book Lives

by Jad Adams

Reaktion Books. 388 ages, $30.

SET IN THE OFFICES of a Victorian magazine that he edited, many of Anthony Trollope’s later short stories fictionalize his encounters with aspiring authors, whether talented or not, ambitious or retiring, male or female, but overwhelmingly the latter. Given the success of Charlotte Brontë, Mrs. Gaskell, and George Eliot, not to mention enormous best sellers like Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret, women flocked to London dead set upon becoming wealthy, celebrated authors.

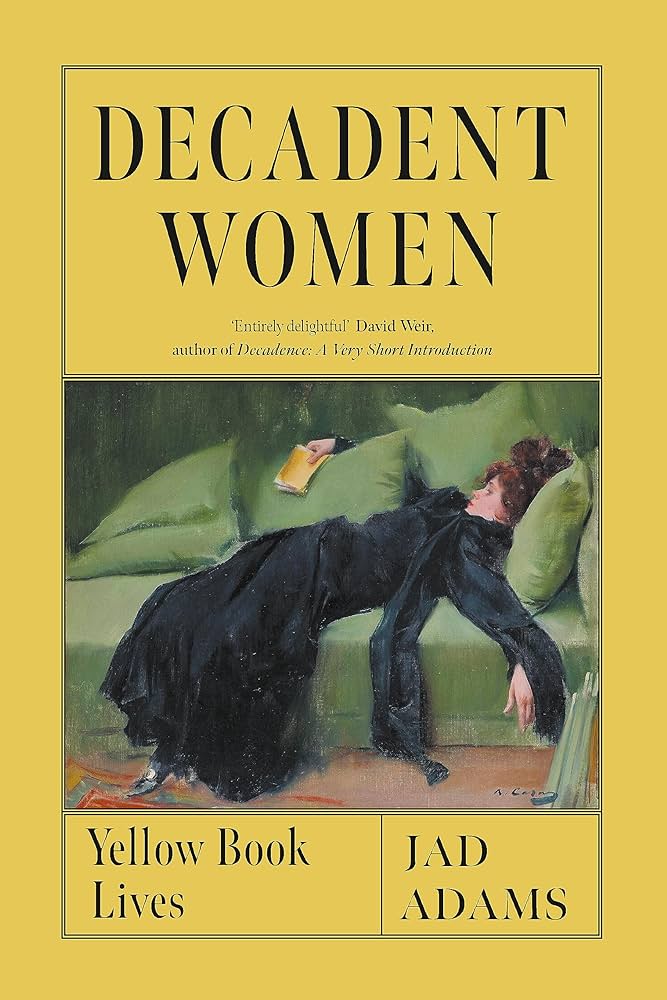

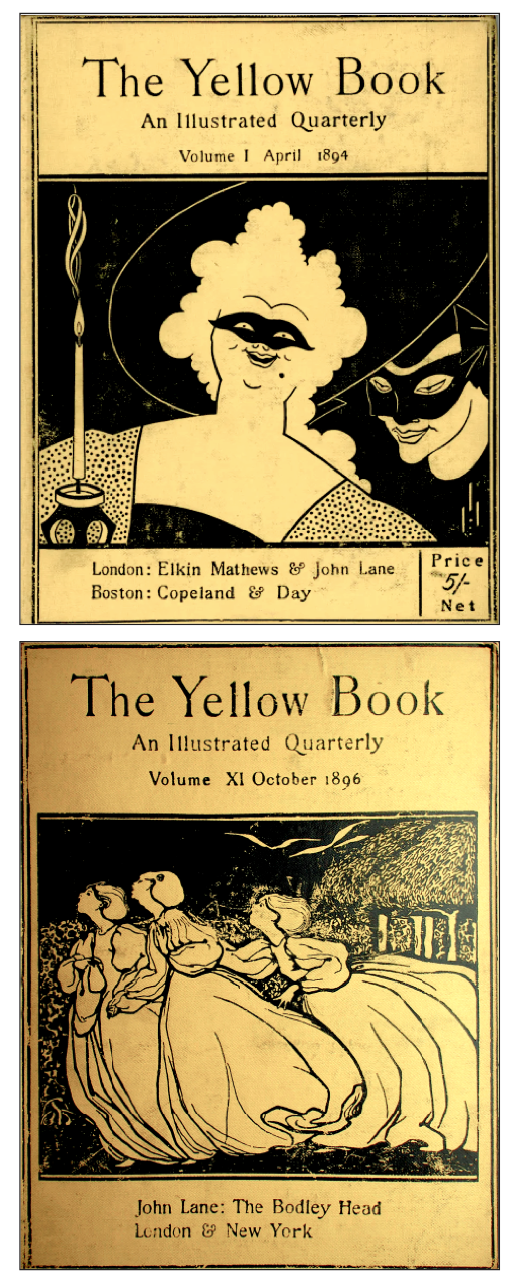

They continued to do so two decades later, especially when a new magazine called The Yellow Book opened its doors to women. Founded by Henry Harland and John Lane, it was a hardcover quarterly ranging from 267 to 414 pages, with numerous wood block illustrations adorning both the covers and the interior pages. It arrived on the literary scene in 1894 and lasted through 1897. But however short-lived, its thirteen issues had an influence of almost mythic proportions on both sides of the Atlantic. A new book by Jad Adams titled Decadent Women: Yellow Book Lives tells the story of this extraordinary burst of literary light, along with that of founders Harland and Lane.

John Lane was the publisher of the Bodley Head, the Grove Press of its day for its edginess and trendiness. Comments Jad Adams: “Lane was fond of beautifully crafted books and women, which gave him the sobriquet ‘Petticoat Lane.’” Henry Harland wasn’t shy either, taking a bit of credit when referring to Evelyn Sharp’s best story as his “darling of my heart, child of my editing.”

The Yellow Book’s greatest achievement was undoubtedly the representation of women writers in its pages. The so-called “New Woman” of 1890s journalism was well represented. (There was a great deal of “borrowing of authors” from the book catalogue to the magazine, and vice versa.) Some of these women, such as Ella D’Arcy, had enormous sway as co-editors and, in effect, office managers. By year two, as much as 47  percent of the featured talent was women, such as au courant poster artist Mabel Dearmer, whose work was frequently showcased. But it was always the two men who did the selecting. They immediately sought fiction from “George Egerton” and Gabriela Cunninghame Graham, who fabricated her name, her ancestry, and really her entire life. Other women were quite successful even after the magazine folded, especially Netta Syrett and Olive Custance, whom Lane called “My little Sappho.” A commercially successful author, Custance had affairs with millionaire writer Natalie Barney, among others, and married Lord Douglas—“Bosie”—clearly a marriage of convenience for both of them.

percent of the featured talent was women, such as au courant poster artist Mabel Dearmer, whose work was frequently showcased. But it was always the two men who did the selecting. They immediately sought fiction from “George Egerton” and Gabriela Cunninghame Graham, who fabricated her name, her ancestry, and really her entire life. Other women were quite successful even after the magazine folded, especially Netta Syrett and Olive Custance, whom Lane called “My little Sappho.” A commercially successful author, Custance had affairs with millionaire writer Natalie Barney, among others, and married Lord Douglas—“Bosie”—clearly a marriage of convenience for both of them.

A crisis that erupted during the course of The Yellow Book’s run was the arrest of Oscar Wilde, which had immediate repercussions for the magazine. It’s not that Wilde ever contributed, but when Lane landed in New York and saw headlines and photos of Wilde being hauled off to jail with a copy of The Yellow Book under his arm, he saw to it that Beardsley and his openly effeminate gay set got the axe. Lesbian writers like Charlotte Mew went even deeper into the closet. Note that the term “decadent,” so closely associated with Wilde, appears in Adams’ title. Contemporary definitions of “decadence” were rather vague. Adams settles on Jerusha McCormack’s later definition of decadence as “a kind of counter-culture, generally employed as anything that appeared to threaten the conventions, moral and social, of the Victorian middle classes.”

Several bisexual women whom Adams highlights didn’t bother to hide. Ménie Muriel Dowie had traveled alone dressed “in a shirt and knickerbockers (with detachable skirt) and boots during her early twenties—through the British Isles, Europe, and even the Carpathian Mountains while barely of age, and wrote travel books with ill-disguised female love interests.” During this time, “[s]he washed in streams; she lost her watch; she bandaged a servant’s finger with bread and cobwebs; she practiced shooting, prepared to encounter a bear.” In her first novel, she even advocated for obstetric surrogacy. But once she had achieved literary fame, she married and became one side of a scandalous triangle with two men.

Several of the women’s lives ended tragically, including the physically small Charlotte Mew, described by Virginia Woolf as “the greatest living poetess.” Thwarted in all her lesbian romances, she inherited wealth from an uncle, but then lost her friends to the Grim Reaper, fell into despair, and ended up institutionalized. Evelyn Sharp became an ardent Suffragette Warrior and endured the legal and then financial consequences. Several women lived well into the 20th century, experiencing both world wars and the accompanying poverty.

Others, such as Vernon Lee (Hauntings) and Ellen Nesbitt Bland (The Treasure Seekers), developed solid careers as authors of the supernatural and young people’s books. Unsurprisingly, among Lane’s best-selling Bodley Head titles were collections of fairy stories that featured many female contributors, as well as Kenneth Grahame’s best-known works of fantasy, The Wind in the Willows and The Golden Age. He and other male writers, like Henry James, considered The Yellow Book just another outlet for their stories. James chose it for one of his queerest tales, “The Death of the Lion,” in which the gay protégé of a famous novelist makes a surprising discovery at a literary country house. As for Beardsley, after he was fired, in effect, for being gay, he and his entire circle moved on to a new venue, The Savoy, which soon surpassed its predecessor in daring and æsthetic appeal. But for many women, The Yellow Book was a crucial step in their communication with each other and with the world.

Decadent Women: Yellow Book Lives is a surprisingly readable, even page-turning, book. Jad Adams has researched deeply into an under-studied pocket of literary women and queer literary life in Britain. He presents their portraits with the narrative sweep of a fine novel, or perhaps a novel of linked stories. The book is profusely illustrated with useful and clever graphics and photographs of these remarkable women and their creations.

Felice Picano’s 1985 novel Ambidestrous: The Secret Lives of Children, has recently been republished by Beautiful Dreamer Press.