The Tennessee Williams Festival in New Orleans is 31 years old this year. Next year, its smaller sibling, The Saints & Sinners Festival, will celebrate its 15th anniversary. After years of being held at separate times, they are now held together, in the last week of March. (Williams’ birthday was March 26th.)

The Tennessee Williams Festival in New Orleans is 31 years old this year. Next year, its smaller sibling, The Saints & Sinners Festival, will celebrate its 15th anniversary. After years of being held at separate times, they are now held together, in the last week of March. (Williams’ birthday was March 26th.)

I have attended both events separately for years, and once again I attended this conjoined one, as a reader, panelist, award giver, and—new for me this year—as the presenter of a program. There are other celebrations of the American playwrights who has come to be accepted as one of the three greats (along with Eugene O’Neill and Arthur Miller)—annually in Provincetown, in Key West, and in St. Louis. Given how well Williams’ expansive corpus of work has held up, many of us have come to believe that Williams is the greatest of the three.

The Hotel Monteleone, that yellow stucco centerpiece in the French Quarter with its slowly rotating Carousel bar and its many ballrooms and conference rooms, has been the scene of the two festivals for years. During the festival weekend, its large, genial lobby hosted smaller groups of the New South’s wealthier patrons and their well-dressed scions. It’s a mixture of cultures that seems to work well for all concerned.

For TW Fest-goers, new productions of the plays are intrinsic to their attendance. In the past, luminaries like Keir Dullea, Stephanie Zimbalist, Kim Hunter, Alec Baldwin, Elizabeth Ashley, Dixie Carter, and John Goodman starred in excellent revivals at the antique Le Petit Theatre. This year, two longer-run productions were available: Southern Rep’s imaginative, dynamic revival of Sweet Bird of Youth at Loyola University, and a vividly realized production of The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore in the Faubourg Marigny. Smaller productions of all but unknown earlier plays included “Now the Cats with Jeweled Claws,” “Loneliness and Desire,” and the fragment “At Liberty,” directed by the festivals’ director, Paul J. Willis, at the Keyes-Beauregard House.

For many at the TW Festival, big name authors are de rigueur. This year, Dorothy Allison, Rick Bragg, Brad Richard, Roy Blount Jr., Robert Olen Butler, Wally Lamb, Dick Cavett, Winston Groom, Patricia Bosworth, and others fulfilled that function. Their panels were enormously well-attended in the ballrooms. Among the local stars were Frank Perez, who gives a Williams Walking Tour, and scholars such as Kenneth Holditch. In previous years, John Lahr and other name authors have been interviewed. But as we have grown further away from contemporaneity with the playwright, these larger panels, while entertaining, have begun to lose much of their relevance.

By contrast, presentations at the smaller Saints and Sinners Festival remain trenchant and at times exciting. Dorothy Allison’s wit and sincerity worked well alongside Appalachian gay poet and novelist Jeff Mann in Eric Andrews-Katz’ “In the Writer Studio” interview. We got a deeper look into the lives and work problems of these authors in that more intimate venue. Likewise, local writer Susan Larson, who used to review for the Times-Picayune and now hosts a lively current book show on public television out of New Orleans University, hosted a panel on the subject of “reading as revolution.” The panelists were New Orleans resident and mystery author Jean Redmann (The Intersection of Law and Desire), novelist and commentator Andrew Holleran (Dancer From the Dance), poet-novelist Carol Rosenfeld, and myself. Unlike some of the more superficial events upstairs, this and other Saints and Sinners events dug deep into the current ethos. For example, on the previous day a panel with Carrie Smith, Michael Thomas Ford, Tom Mendocino, Tammy Lyle Stoner, and me dealt with the effects of the “mainstreaming” of gay and lesbian culture, especially among younger generations.

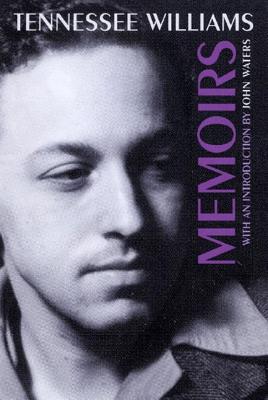

What unites the two Festivals, of course, is the fact that Tennessee Williams was himself gay, and that in his Memoirs, his later plays, and his fiction he wrote quite openly from the viewpoint of a gay man in a non-gay society. One of the TW panels was titled “New York in the 70s,” moderated by eminent Williams scholar Thomas Keith. But it  didn’t more than touch on the subject of Williams himself in New York during that period. He was recovering from a nervous breakdown and got well enough to complete several plays and to become a social figure in the artistic life of the city. By then he’d given up on Broadway productions and mainstream critical attention. Yet his newer plays were all over Lower Manhattan. To boost sales in Small Craft Warnings, Williams himself took the stage as the narrator playing opposite his star, Candy Darling. He fit in easily with the Warhol crowd and with other professionals of the Ridiculous Theatre world then in ascendance.

didn’t more than touch on the subject of Williams himself in New York during that period. He was recovering from a nervous breakdown and got well enough to complete several plays and to become a social figure in the artistic life of the city. By then he’d given up on Broadway productions and mainstream critical attention. Yet his newer plays were all over Lower Manhattan. To boost sales in Small Craft Warnings, Williams himself took the stage as the narrator playing opposite his star, Candy Darling. He fit in easily with the Warhol crowd and with other professionals of the Ridiculous Theatre world then in ascendance.

Whenever I would come upon Tennessee in these situations, he seemed relaxed, at home, finally able to be himself. It was almost as though, after years of wandering, he had at last found a new home. Perhaps it’s a good thing that he died when he did, because that congenial scene was utterly wiped out, first by a virus and then by real estate moguls. The New York City that Tennessee knew is gone, and the New Orleans that he knew is hanging on by its fingernails, revived by an influx of cash after Hurricane Katrina that will probably ruin that city too.

Felice Picano’s latest book is a memoir titled Nights at Rizzoli (OR Books, 2015).