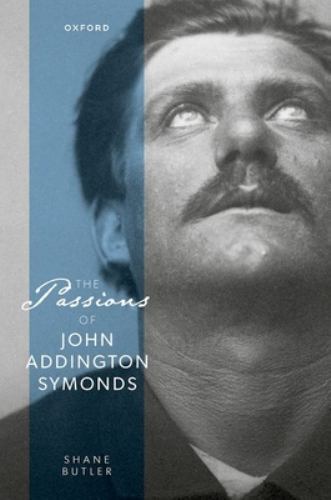

THE TITLE of Shane Butler’s most recent book, The Passions of John Addington Symonds, and the portrait photograph that graces its cover—of a handsome, thick-necked, and mustachioed man looking upward—encourage a set of provocative expectations that will probably not be met. If the word “passions” implies the fever of erotic heat, be prepared for a decidedly cooler temperature. If the book’s striking jacket image is presumed to represent the title subject, be aware that the face in question belongs to one Angelo Fusato, a Venetian gondolier who in the 1870s became both a lover and a household servant to the British writer John Addington Symonds (1840–1893). If you are at all familiar with Symonds’ writings or his life, then you know that homoerotic attractions were central to his life and thought, yet hardly produced a temperament we would call gay—in either its older or current meaning. And yet, for all that, it was Symonds who first imported the word “homosexual,” a 19th-century coinage of German origin, into English print.

The Passions of John Addington Symonds cannot be characterized as a “biography” in the usual sense. Professor Butler’s project is a work of impressive and sometimes frightening erudition. I fear that even among today’s reasonably educated LGBT readers, few will have the background in Classical literature, in the arcane scholarship and mandatory language of queer theory, or in the foundational texts of the West’s philosophical canon (from the ancients to the postwar French, i.e. Deleuze, Derrida, Foucault, Lacan) to appreciate Butler’s most theoretical and discursive inquiries, of which there are many.

The organization of the book’s chapters corresponds to the various intellectual inquiries in which Symonds was engaged throughout his life. For example, in a chapter titled “Homer’s Deep: Ancient Greece and Reciprocal Love,” Butler reviews Homer’s rendering of the relationship of Achilles to Patroclus and its multiple interpretations and meanings over the years—a friendship? a chaste “Platonic” love? a model of ancient pederasty dependent on differences of age and status? He traces the changing analyses by later Classicists, literary critics, and emerging sexual historians who, like Symonds himself, have grappled with homosocial or homoerotic interpretations according to the mores and beliefs of their times.

But let us back up to locate John Addington Symonds in his time. He was born in the port city of Bristol. His father, the senior John Addington Symonds, was a successful physician. His mother died early and young; Symonds retained few lasting memories of her. Ultimately, his father moved the family to the more bourgeois and respectable town of Clifton, though by then young John’s experience of Bristol, the “sometimes perilous port and its sailors,” had become the source of his earliest sexual fantasies, which years later he recorded in his Memoirs, which remained unpublished until 1986. By age thirteen, he was off to Harrow, the all-boys school where Symonds was introduced to “rampant sexual activity among the boys.” Later, at Oxford, the Plato scholar Benjamin Jowett was his mentor. It was at Oxford that Symonds “began expressing his desires in classicizing poems.” At age twenty, he was awarded a distinguished university prize for English verse, and three years later, he received another Oxford honor for an essay he’d written on the Renaissance. By 1864, having met and married Catherine North, the pair was living in London, Symonds was preparing for a career in law, and over time the couple had four daughters.

In 1871, after the death of his father, Symonds moved his wife and children to the grand family manse of his childhood, Clifton Hill House, where, due to ill health from tuberculosis, he abandoned the law and took up scholarly pursuits, publishing on a range of topics in British periodicals and assembling his previous articles on “Greek literature, on Dante, and on Italian travel” into a book. He lectured at Clifton College, and there fell in love with one of his male students. He published some poetry, often changing the gender of the pronouns, while also privately printing “more explicit pieces” to share with friends. As the effects of tuberculosis became more acute, he moved the family to Davos, Switzerland. He frequently traveled further south, especially to Venice, where he made the acquaintance of the gondolier Angelo Fusato and brought him into the family, so to speak.

In Davos, Symonds established a collegial friendship with Robert Louis Stevenson, author of such popular fare as Treasure Island and Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, who was a fellow disabled person. In a middle chapter subtitled “Symonds, Stevenson, and the Divided Self,” Butler uses the duality posed in Stevenson’s Jekyll and Hyde to interrogate the unlikely friendship of the two writers and Symonds’ rather tortured psychic life and his avoidance of uttering some core personal mystery. Symonds also engaged in what Butler describes as a “somewhat anguished correspondence” with the American poet Walt Whitman, which was generally an exchange of mutual regard. Yet when Symonds pressed the American bard for more frank clarification of the “sexual implications” in Leaves of Grass, the wily Whitman replied in a manner that struck Symonds as a near brutal rebuff, for he repudiated any such intended construction of the “Calamus” poems.

Throughout the years before and after the onset of his illness, Symonds wrote prolifically, including work on Greek sexuality that would become his influential, privately printed essay A Problem in Greek Ethics, the companion to A Problem in Modern Ethics. This pair of volumes became the foundation for his “collaboration by correspondence” with Havelock Ellis on Sexual Inversion. Meanwhile, Symonds’ seven-volume study, The Renaissance in Italy, was published between 1875 and 1886.

While Butler’s biographical summary is covered in a few pages in the introduction, the preamble runs to 41 pages. Near the end, he feels required to make the following statement: “Occasional stretches of the book to follow will seem not to be ‘about’ Symonds, stricto sensu. Or rather, this book will oscillate between two meanings of ‘about.’ Sometimes, Symonds will be our central subject. At other times, our attention will be directed instead to things that swirl around and about his thought and work.” Just how “occasional” these stretches are is open to question, for we might justly characterize each of Butler’s chapters as detours of argumentation prompted by a text, a renowned literary personage, or a work of art, or all combined.

Some of these detours provide piquant information or propose provocative lines of inquiry. In an early chapter on Dante, Butler spends time on the matter of the photographic frontispiece Symonds used for An Introduction to the Study of Dante, first published in 1872. The image was a plaster cast of the purported death-mask of the Italian poet, though not captioned in the first edition. Butler takes pains to detail the source of Symonds’ misattribution but then offers mini-treatises on the place of photography—that new invention from the mid-19th-century—in documenting the Symonds family, in the collecting habits of period photo-erotica by Symonds himself; in the medium’s integration into printed books; and in jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes perfecting an inexpensive “stereoscope” that enabled viewers to examine “pairs of photographs taken from slightly different vantage points that, with one placed before each eye, generated the illusion of a three-dimensional view.” We then move to philosophical ruminations on this “opto-haptic nexus” and how “sculpture is always an invitation to touch, or at least an invitation to imagine touching” and eventually, how the “the stereoscope’s synthetic illusions … themselves depend on the eye’s learned ability to function as a shortcut to knowledge that would otherwise have to be obtained through movement and touch.” It’s easy to imagine a reader losing track of the main argument—and this doesn’t even consider the many content footnotes that support particular lines of inquiry or inject some fresh parenthetical reflection by Professor Butler.

One of Butler’s principal objectives is to give Symonds the credit he’s due, credit that was withheld in part as a consequence of his early death at age 52. Another factor is the complicated history through which Symonds’ private letters, memoirs, and other papers were either suppressed, embargoed, or thrown to the fire. His Memoirs, “two hulking manuscript volumes,” for example, were given over to the private, subscription-based London Library in 1926 by Symonds’ friend and literary executor, Horatio Forbes Brown, who imposed a long embargo on consultation or publication that lasted until 1984. Brown was also Symonds’ first biographer, making use of the memoirs but selectively editing material referencing the writer’s “homosexual life” so as to protect such knowledge as a “‘secret’ to the wider public, and even to many intimates.” Other papers that were part of the Brown bequest were taken in hand by the poet and critic Edmund Gosse, “chairman of the library’s committee of direction,” and he eventually burned them with the help of another librarian. As Butler acknowledges: “the bonfire had been lit long before all this—and by none other than Symonds himself. From the start, he was forever asking his friends to destroy handwritten or privately printed copies of too-revealing works sent to them for review.”

He continues: “From the burning and burying of Symonds’s poems in the 1860s to the publication and reception of [Phyllis] Grosskurth’s biography in the 1960s, we have quickly bookended what already reads as an epic tale of suppression and censorship over the course of a century—indeed, a century and a half, if we instead take the 2016 publication of the unabridged memoirs as its endpoint. They are distinguished by the fact that the censors are not clerics, policemen, or angry mobs but instead insiders: friends, family, and even Symonds himself.”

Butler, of course, is not constrained by the same squeamishness that plagued the writers of the Victorian period who lived under an enforced regime of silence concerning the love that dared not speak its name. He gives a tantalizing account of the variously subtle codes by which we in our time can decipher the textual references of Symonds himself and such literary eminences as Henry James, Walter Pater, and Oscar Wilde in a chapter titled “Queer Sensibilities.” To different degrees, we might conclude what Butler understood of the various dodges engaged in Symonds’ texts as applying to others from that time: “This story is as much one of the circulation of secrets as it is of their definitive concealment. … Indeed, one is inclined here to note the obvious: that there surely can be no worse way to keep a secret than to write it down, to say nothing of having it printed, even privately. … Symonds’s ‘secret homosexual life,’ in retrospect, often seems to have been hiding in plain sight all along.”

We find in The Passions of John Addington Symonds a good deal of engaging commentary and original interpretation, but it remains a work of contemporary scholarship aimed less at a general readership than at other scholars in the field. Its language, while not consistently lapsing into the opaqueness of academic jargon, nevertheless does not invite a spirit of shared conversation. That said, Butler’s own passion for Symonds makes this text foundational ground for reading. It points us to essential literary examples from ancient times, through the Renaissance, and on to the Victorians. Butler’s scholarship is deep and wide, frequently enlisting obscure journal articles by both established and emerging scholars. Most importantly, for those inclined to explore a central figure in the formation of a queer history, The Passions of John Addington Symonds points one to the letters, the memoirs, and the prime Symonds texts that would feed into the emerging disciplines of sexology and psychoanalysis and the coming cataclysm of Freudian thought.

Allen Ellenzweig, a longtime G&LR contributor, is the author of George Platt Lynes: The Daring Eye (Oxford, 2021).