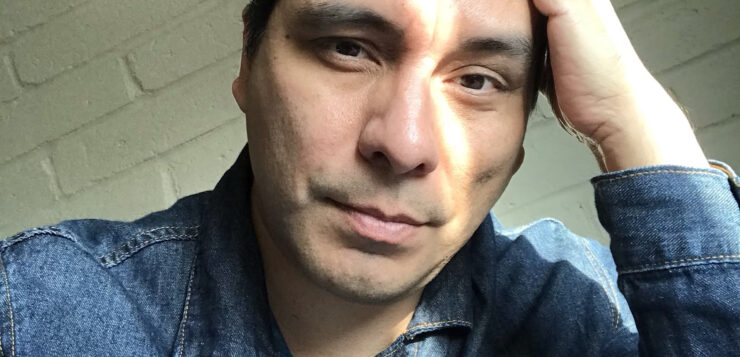

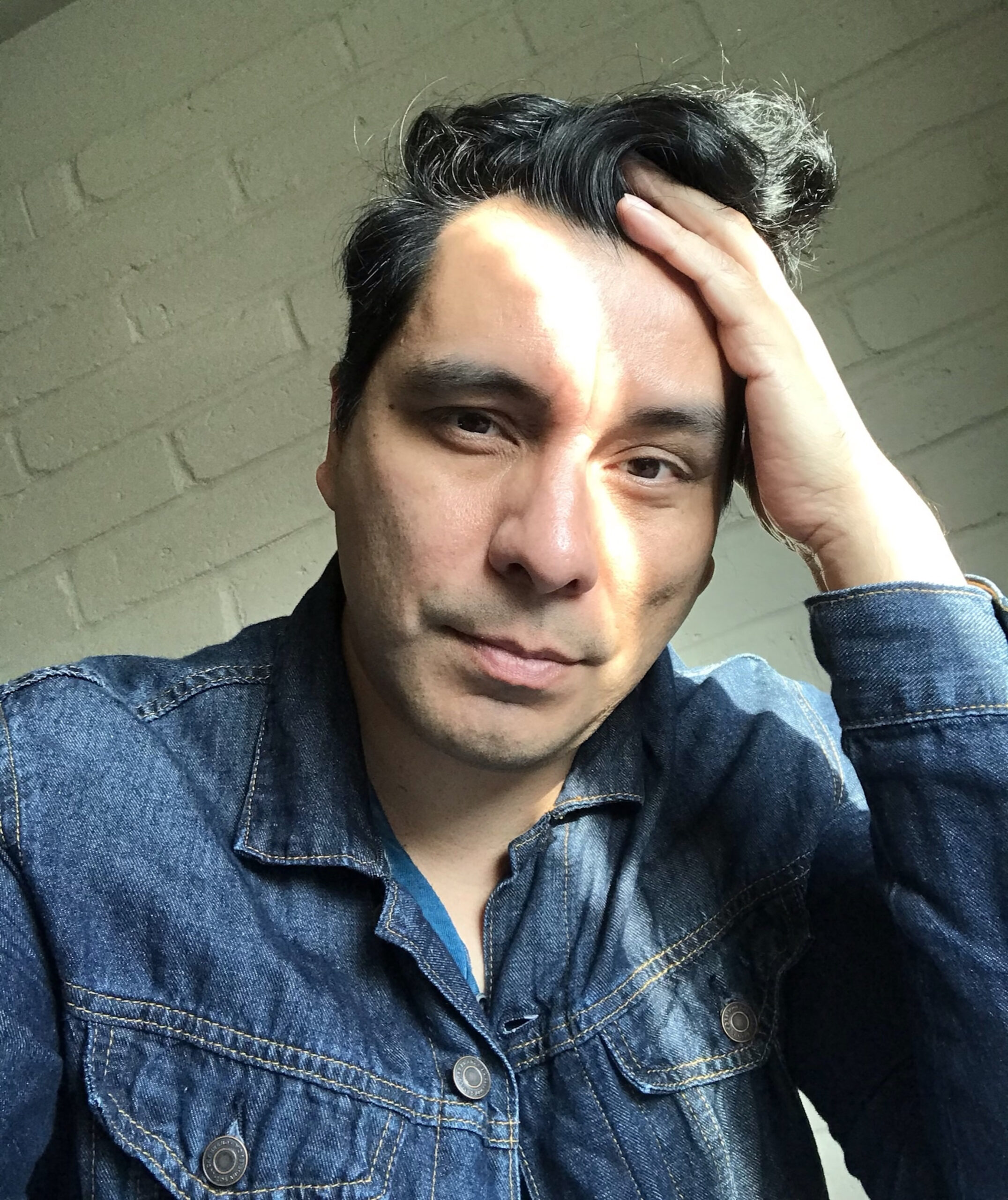

WRITER AND EDUCATOR Manuel Muñoz grew up in Dinuba, California, a primarily agricultural community near Fresno. From an early age, he helped his family in the fields and, later, packing produce for shipment. The youngest of five children, Muñoz is the only one to have left the area. He attended Harvard College and received an MFA in creative writing at Cornell University.

Muñoz began publishing his short stories in literary journals, both LGBT-oriented and mainstream, around the turn of the millennium. Focusing on the San Joaquin Valley in which he grew up, his stories address issues that he observed intimately: immigration, poverty, farm labor, family ties and their unraveling, and where queer characters fit (or don’t) into that environment. He has published three collections of short stories and a novel. He’s won three O. Henry Awards, among other honors. He currently lives in Tucson, Arizona, where he teaches at the University of Arizona.

Muñoz began publishing his short stories in literary journals, both LGBT-oriented and mainstream, around the turn of the millennium. Focusing on the San Joaquin Valley in which he grew up, his stories address issues that he observed intimately: immigration, poverty, farm labor, family ties and their unraveling, and where queer characters fit (or don’t) into that environment. He has published three collections of short stories and a novel. He’s won three O. Henry Awards, among other honors. He currently lives in Tucson, Arizona, where he teaches at the University of Arizona.

This interview was conducted via telephone in late October, the week after his most recent collection, The Consequences, was published.

Neil Ellis Orts: One of the recurring themes in your work is class. When I read your first collection, Zigzagger, I was in grad school and acutely aware of how my rural childhood differed from the urban lives of my classmates. Your story “Zapatos” gave me a different framework for understanding my experience.

Manuel Muñoz: I’m really glad you led with that. Class tends to be the last thing in a series of words people would use to describe my work. Often, they go to race and ethnicity or sexuality, and where I identify or place myself within queer literature. For me, class has been the dominant strain and the one where the most conflict bubbles up. Even in that small micro story you mentioned, it gets to the root of how we describe experiences to each other.

NEO: There are also generational divides in your stories, almost always connected to labor but also between people who leave for something different if not better. You’re a university professor from a rural community. Do you experience a divide?

MM: It depends upon what I’m doing and where I am. I take tremendous pride being in front of my classroom. I know what it means to a lot of first-generation students in my class who come from communities like mine. “That’s my professor. His brown face is like my brown face.” That’s important as they’re growing into awareness of how often they’re not seeing people like them in positions of influence. Is it different when I go home? Sometimes. Those economic stresses are still in my family. But there isn’t a conflict [with the family]. I think my family recognizes what I can contribute. There are so many ways to answer that question, but it’s not the kind of conflict where there’s any sort of estrangement between me and my family and my community. If anything, it’s celebratory. It’s one of the reasons why we had the official book launch [for The Consequences]at Reedley College, which is the community college near my town. The majority of the audience is going to be students who come from towns just like mine. It’s really joyous for a lot of them. It’s the first time they’ve ever seen someone come to the Valley, and is from the Valley, and is talking about making art, writing about the place. I’m very proud of it.

NEO: Something I think about is how queer life has changed in the last twenty years, and how it hasn’t changed at the same pace everywhere. It feels like this changes the nature of the coming out story. Do you think about this?

MM: I really love this question. You phrased it beautifully: all these changes that have come but haven’t come at the same time. It really depends upon where we are, geographically but also economically. When I think about it in context of my work, one of the reasons I struggled to publish my first book is that there weren’t venues that were going to take on not just the queer experience but that experience within my community. I remember one press that rejected Zigzagger said to me, the Latino community was not ready for these kinds of stories. My generation of writers was just starting to publish and I was already familiar with, for some people, how repetitive the coming out story had become, but for my community, they were just starting. So, it was very painful to hear those conversations, to be quite frank. I was just at UC Santa Barbara at the Las Maestras Center with Cherrie Moraga and we were talking about a couple of stories in The Consequences that exhibit just how powerful the closet really is. Just because some people have stepped out of it doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. It certainly does, especially for people in rural communities and people whose family situations are such that it makes it difficult to live their true lives. I’m very interested in narrating those stories. I think those stories are quite rich.

The story “Compromisos” in The Consequences is about a man who had left his family and had gotten involved with a younger man. He’s now looking for a way to come back because he realizes the guy that he’s been messing around with isn’t interested in a relationship. He has to think about what he wants. That story has its roots in a date I went on here in Tucson about 10 years ago. It was a guy who was essentially in the same situation. He was in his late thirties and had a child but had come out late in life and didn’t know how to deal with it. One of the painful things he told me was that he was thinking about going back to his family. When I was sharing this with a couple of friends of mine, I was startled by their judgment of him. “Great way to fuck up your family!” I thought, well, this is what he wants to do, what he feels is necessary. What you see as a giving up all these experiences is negating one of his, which is he has a child. He wanted to make sure his child has two parents and a home. That kind of conflict for me as a writer is always a draw—the kind of situation I can write about where I don’t judge somebody for the decisions that they’re making, especially when their choices are limited to begin with. That to me is the stuff of poignancy, it’s the stuff of high drama. And of humanity, to be honest with you.

NEO: In some of the circles I inhabit, the conversation is about wanting role models or at least fewer sad queer characters, and I understand that, too, but those stories often don’t feel real to me.

MM: Sometimes the conversation is about what stories to tell, how many of them have been told enough. I understand what it means in terms of liberation, but you also don’t leave people behind, and those experiences happen even now, especially in places like my hometown. Their question of what is the right thing to do is a very different question. I’m very much about honoring as many of those stories as possible.

Neil Ellis Orts, author of the novella Cary and John (2020), is a writer based in Houston.