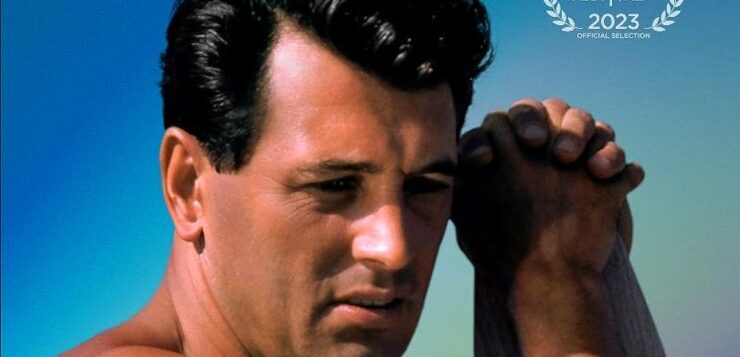

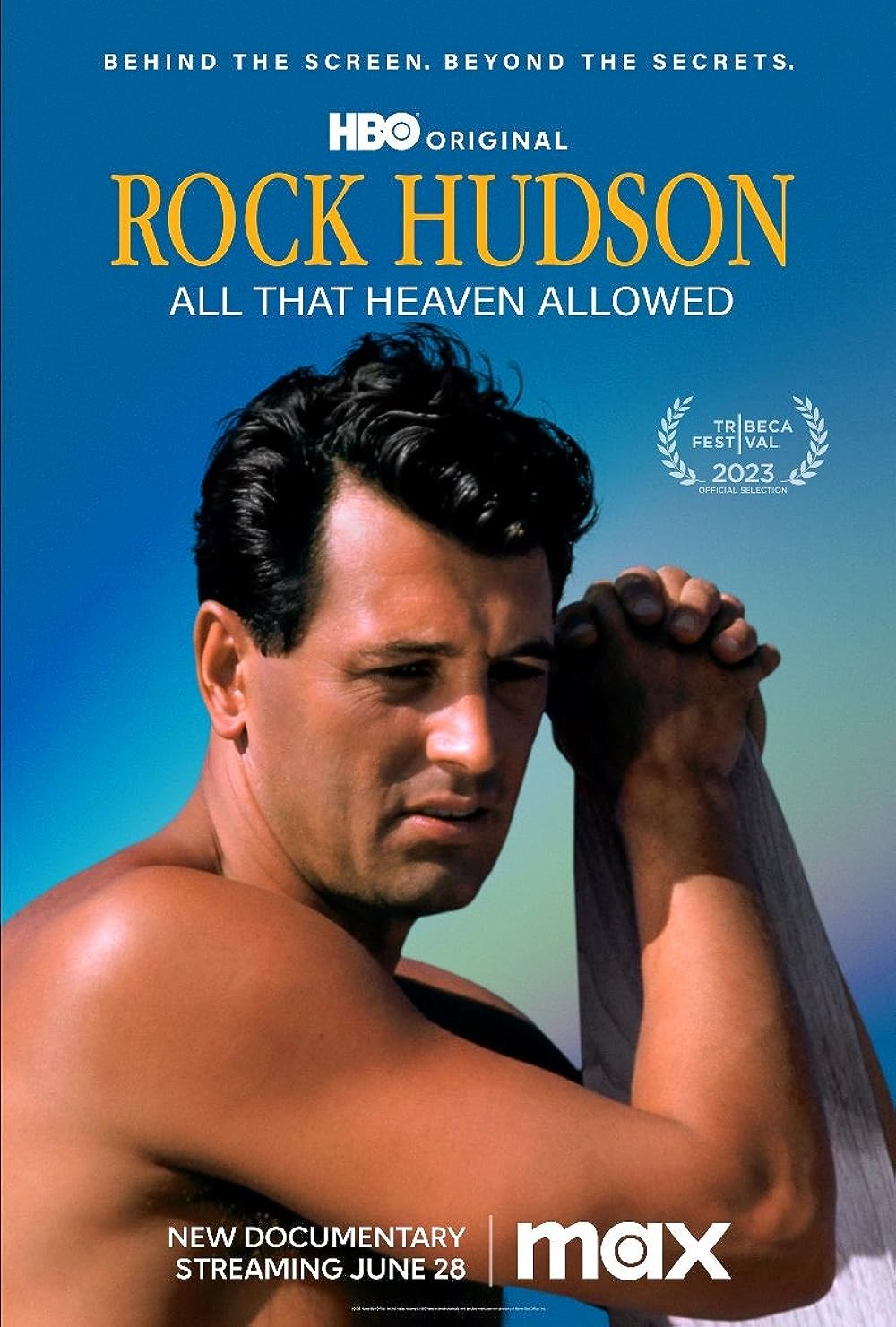

ROCK HUDSON was the biggest heartthrob of midcentury cinema, once billed as the “most wanted man in America,” but also the most famous film star to die of AIDS. A new documentary, directed by Stephen Kijak, has set a critical reappraisal of his career in motion. It explores the ways in which Hudson, forced to lead a double life, was the sacrificial lamb of the studio system.

Based on Mark Griffin’s 2018 biography of the same name, Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed offers us a glimpse into his career but also into the AIDS crisis. This falls on the heels of Hollywood (2020), the Netflix series in which director Ryan Murphy presented a fictionalized version of Hudson as an Illinois-born boy arriving in Tinseltown by Greyhound bus and living in secret with his Black boyfriend Archie. Kijak’s documentary wants to show how Hudson was the ultimate victim of the “celluloid closet,” as film historian Vito Russo called it back in 1981. This was the same year in which Hudson underwent quintuple bypass heart surgery due to his pack-a-day smoking and alcohol intake. In his poem “To the Film Industry in Crisis” (1955), poet Frank O’Hara refers lovingly to the movies as the “glorious Silver Screen, tragic Technicolor, amorous Cinemascope.” Glorious, tragic, amorous—Hudson checked all the boxes.

The sense that Hudson, the leading man of the postwar generation, somehow misled his fans first erupted in 1985 after he appeared in an interview alongside a squeaky-clean Doris Day, his longtime costar and onscreen beard. He looked unrecognizable: gaunt and pale. That October, the actor’s publicist was forced to disclose: “Mr. Rock Hudson has Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome.” This not only shocked his fans but, more significantly, it rattled Ronald Reagan into finally addressing a disease that he hoped would just go away. Hudson was a personal friend of Nancy Reagan—she even urged him after a state banquet to have a “pimple” on his neck checked—and after his status had been disclosed, Griffin writes: “Suddenly, from the White House to Frank’s Diner in Kenosha, everyone knew someone who had AIDS.”

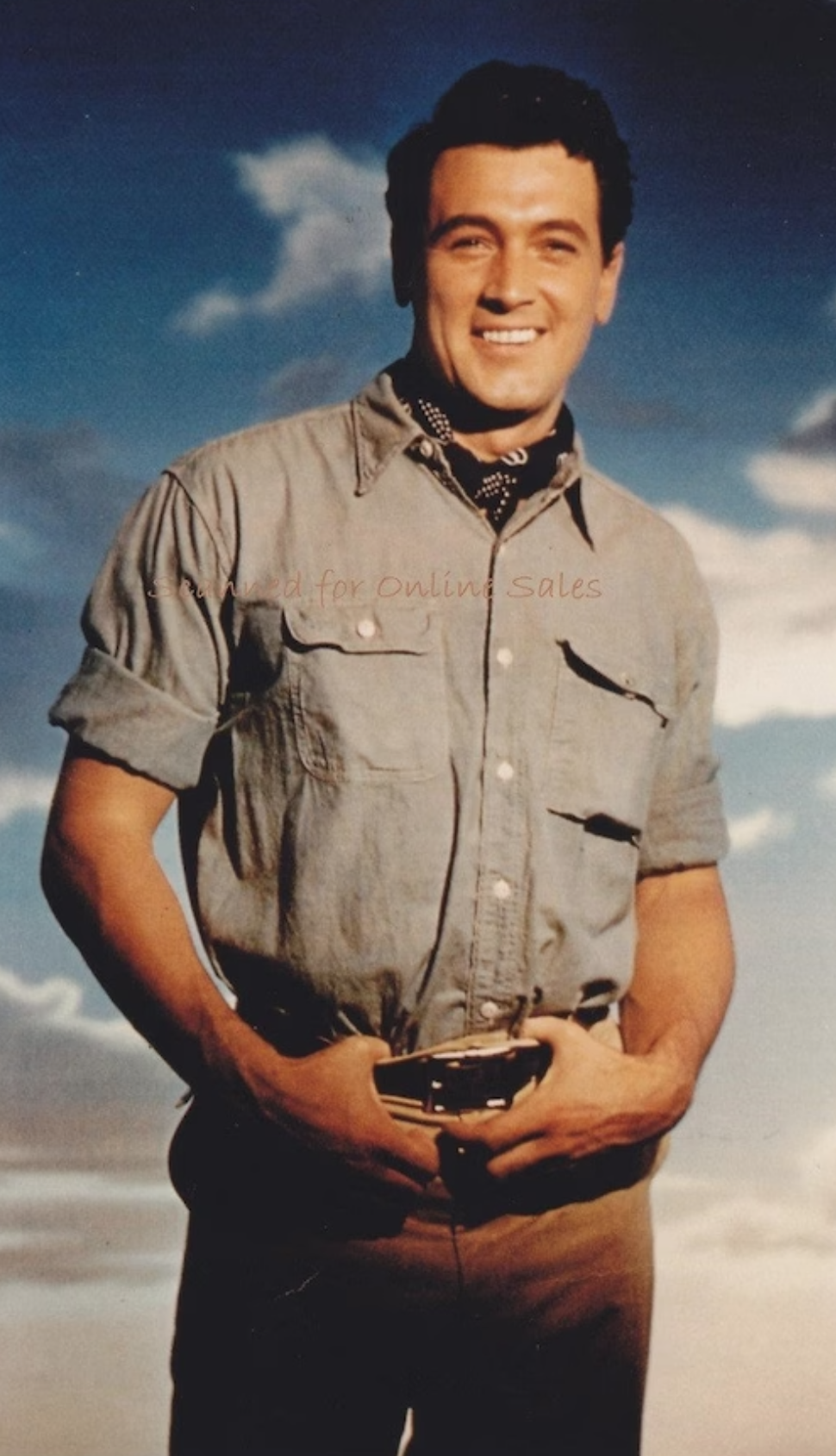

What’s in a name? What one commentor speaks to in a discussion of Hudson’s performance in Seconds (1966), a diversion into a darker genre that his fans rejected, is another kind of crisis. It’s deeper than the façade of one’s stage name. “It’s a weird thing to make your living making characters,” says director Allison Anders, “there is always the sense of who am I really.” Since Anders is alluding to a lifelong identity crisis, one must ask, who was “Hudson” and the sandy rock upon which he was built? We know for certain that he born in 1925 and named Roy H. Scherer, Jr. His mother Katherine, after a bitter breakup with his biological father, Roy Scherer, remarried a Marine named Wallace Fitzgerald, which resulted in a second renaming: Roy Harold Fitzgerald. He hated his stepfather and, after joining the Navy, ran off to California. In 1947, yet another shady father figure named Henry Willson, a Hollywood agent, would capitalize on Hudson’s square jaw and six-foot-five-stature and rebrand him as the sex symbol known as “Rock Hudson.”

As Kijak’s film makes plain, the titles of Hudson’s biggest hits take on a different meaning once we acknowledge that his homosexuality was hiding in plain sight. Zoom in, first, on Giant (1956), a perfectly apropos title for a family saga that went one hour beyond its projected running length and 44 days beyond its projected shooting schedule. Giant united three beauties all under the age of thirty: Hudson (then 28) and costars Elizabeth Taylor and James Dean (both 23). Dean would die in his Porsche 500 shortly after production wrapped. As a handsome horse-buyer named Jordan “Bick” Benedict, Jr., Hudson travels from Texas to Maryland to purchase the Benedict family’s studs. Questioned about the size of his ranches, he is polite at first but, without slamming his plate, loses his patience: “It’s big alright!”

Zoom in, second, on Send Me No Flowers, where Hudson shows his acting chops when comic timing is needed. In the role of George, he plays a hypochondriac husband who convinces his wife Judy (Doris Day) that he has only months to live. The bromance lies in his relationship with Arnold (Tony Randall) as the two embark on a queer quest to see who in the neighborhood will replace him. It makes a mockery of marriage, and a cameo by Paul Lynde—a mortuary director flummoxed by George’s request to be interred alongside his wife and another husband—puts a lavender ribbon on the whole affair. Send Me No Flowers throws a grenade into Eisenhower-era family values and, like many a successful satire, appears all kind and gentle on the surface.

The only serious misstep in Kijak’s documentary is the inclusion of “Phone call between Rock Hudson and friend,” a taped conversation that was later leaked to the tabloids. The call dates back to 1974. Sounding more like a pimp than a pal, the “friend” calls the star to report that some sexy young ingenue has just been signed by Paramount Studios and that Hudson would likely want to get his hands on this fresh meat. He is a “damn fine boy,” 6’2”, and “very good in that department.” But who is this so-called “friend”? Without any context, the film then rushes into a humble brag by Armistead Maupin, who confesses that he, too, had his pants “charmed off” of him by the rock-hard Hudson. Based on what Kijak is presenting, who didn’t? The problem is that the “phone call” leaves Hudson sounding like a Watergate burglar and, worse, a forerunner of Harvey Weinstein, the disgraced film producer and sex offender who exploited young actresses left and right. Biographer Griffin does a better job than Kijak at connecting the dots between Hudson and Willson, the agent responsible for repackaging Roy Harold Fitzgerald as “Rock Hudson” and putting his name in lights. “In light of the Weinstein scandal and the many firings and resignations that followed,” writes Griffin, “Henry Willson’s notorious brand of star-making seems deserving of its own hashtag.”

Even if All That Heaven Allowed falls short of radicalizing Hudson’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, it does jumpstart the conversation about his life and legacy even if so many questions remain unanswered. Oddly, Rock Hudson is a film star still waiting for his closeup.

Colin Carman, professor of English literature at Colorado Mesa University, Grand Junction, is the author of The Radical Ecology of the Shelleys.