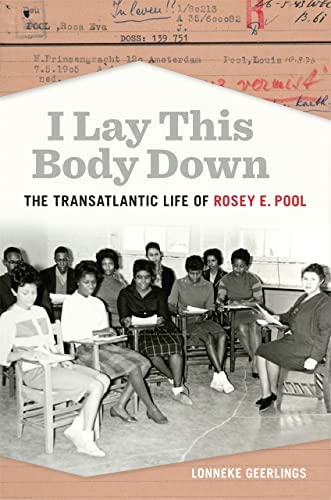

I LAY THIS BODY DOWN

I LAY THIS BODY DOWN

The Transatlantic Life of Rosey E. Pool

by Lonneke Geerlings

Univ. of Georgia. 234 pages, $34.95.

LONNEKE GEERLINGS opens her biography of Rosey E. Pool, I Lay This Body Down, by depicting her subject getting off a cattle car destined for Auschwitz. Convincing the authorities that she was a guard who had lost her identifying armband, combined with her fluent German, served to win her a temporary reprieve. In any event, this quick-witted evasion both saved her life and forever marked her with survivor’s guilt. (This condition became more acute after she learned, years later, that her parents and brother had died in the camp.) A second deliverance occurred when Pool was able to go into hiding because of her pre-war artistic and resistance connections.

Geerlings reports that at the end of the war, Pool’s survival was greeted with suspicion and even cruelty. She had been a member of the Jewish Council, a group whose actions were condemned after the war, and her socialist and anti-fascist activism was disregarded. In addition, because she had gained weight while in hiding, Geerlings speculates that people may have questioned the circumstances of her captivity or even whether she had been imprisoned at all.

It may be that this postwar rejection in her home country is what led Pool to turn her attention to other struggles. Geerlings explains that, although she had not met “one single Negro” before the war, she began to embrace Black interests and causes wholeheartedly. The apartment in London that she shared with her lesbian lover, German-Jewish radiologist Ursel (“Isa”) Eisenburg, became a center of the Black Atlantic Network. While the nature of their relationship ostensibly remained a secret, the two women organized informal salons where they entertained Black writers and intellectuals from around the world, including white and Jewish left-wing activists. Such gatherings proved invaluable to African-American writers like Langston Hughes who were struggling to find publishers at home in the early postwar days, and also to Black writers from Africa and the Caribbean who sought to establish international connections. Pool also published anthologies of Black writing in an effort to support anti-racist resistance movements worldwide.

Geerlings reports that Pool often recounted a memory of her days at the Dutch transit camp when she recited to her block the works of African-American poet Sterling Brown and taught fellow inmates to sing “I Know Moonrise,” an African-American spiritual. Pool recalled that singing this song became a nightly ritual on the block, a calming counterpoint to the sound of cattle cars leaving for Auschwitz. Significantly Geerlings has chosen a lyric from this song as the title of the book, suggesting both Rosey Pool’s affiliation with Black life and longstanding dedication to the causes of social justice.

The epigraph of the biography, however, may be unsettling to some readers. Referring to the Yellow Star that she was forced to wear during the Nazi era, Geerlings quotes Pool: “That piece of yellow cotton became my black skin.” The false equivalency that this statement contains points to Rosey Pool’s personal and analytical blind spots. Indeed as the narrative progresses, some of her activities and attitudes come to seem less and less appealing.

Geerlings notes her mendacity early on. Writing of “the lies she told throughout her life,” she speculates sympathetically: “Whether it was lying about not having carved things in her school desk or prevaricating about attending university or striving to improve herself, Pool was always trying to be somebody other than who she was.” Any lingering compassion may diminish when we learn that Pool relied on her social connections and fabricated educational credentials to secure a Fulbright to the U.S. in 1959 and 1960, at a time when the film The Diary of Anne Frank was popular in the U.S.

The circumstances surrounding this trip show her in an even more uncomplimentary light. While Pool had originally planned to discuss the similarities between Nazi Germany and the Jim Crow South, she quickly switched gears and began capitalizing on the fact that she had taught Anne Frank in Amsterdam during the war. Besides the fact that she profited financially from the trip and often denied being Jewish during the stay, she chose to shock audiences by describing Frank unfavorably, calling her “unremarkable” and “of average intelligence.” Geerlings acknowledges that a partial motive for this cruelty may have been Pool’s belief that there’s nothing noble about suffering in silence, but also surmises that her personal motivation was envy at the posthumous attention Anne Frank was receiving.

A similarly unflattering picture emerges when Geerlings describes the often patronizing and proprietary treatment of the Black writers that Pool included in a 1965 anthology, linking it to the exploitative behavior of white patrons in the Harlem Renaissance. Again, she leaves readers to draw their own conclusions.

Geerlings’ accounts of the two U.S. trips following the Anne Frank visit also cast her subject in an unappealing light. In 1963, Pool secured a position teaching creative writing at Tougaloo College in Mississippi, again under false pretenses. Although she had only been trained as an elementary school teacher, her CV presented a confusing mixture of two fictional degrees and references to friendships with prominent Black intellectuals. While these misrepresentation seems to have worked, Geerlings observes of the appointment that Pool “was still a white person in front of a (predominantly) Black class, and there was no evidence that Pool collaborated with Black faculty members in her classes.”

Clearly, Rosey Pool’s political analysis was deeply flawed, a fact that’s revealed but not interrogated throughout this biography. Similarly, while certain aspects of her professed mission may have been laudable and originally well-meaning, by the end of the volume her dubious outcomes and unsavory personal traits have overshadowed her altruistic projects. In this respect, Geerlings’ sympathetic treatment of her subject seems strangely out of place. He provides ample evidence of Pool’s failings but ultimately withholds judgment, possibly a nod to academic norms (this book started as a doctoral dissertation). Readers, however, are not constrained by the need for scholarly circumspection. While this problematic book does shed light on certain historical alliances and particulars, the general reader may be wise to seek this information elsewhere.

Anne Charles cohosts the cable-access show All Things LGBTQ.