WAKEFIELD POOLE (b. 1936) is an artist and innovator whose work deserves to be taken seriously for its contribution to gay culture and to culture in general. Like many creative people, Poole did not stick to just one medium, but because he became known as a maker of gay adult movies, he has been forever pigeonholed as a film pornographer.

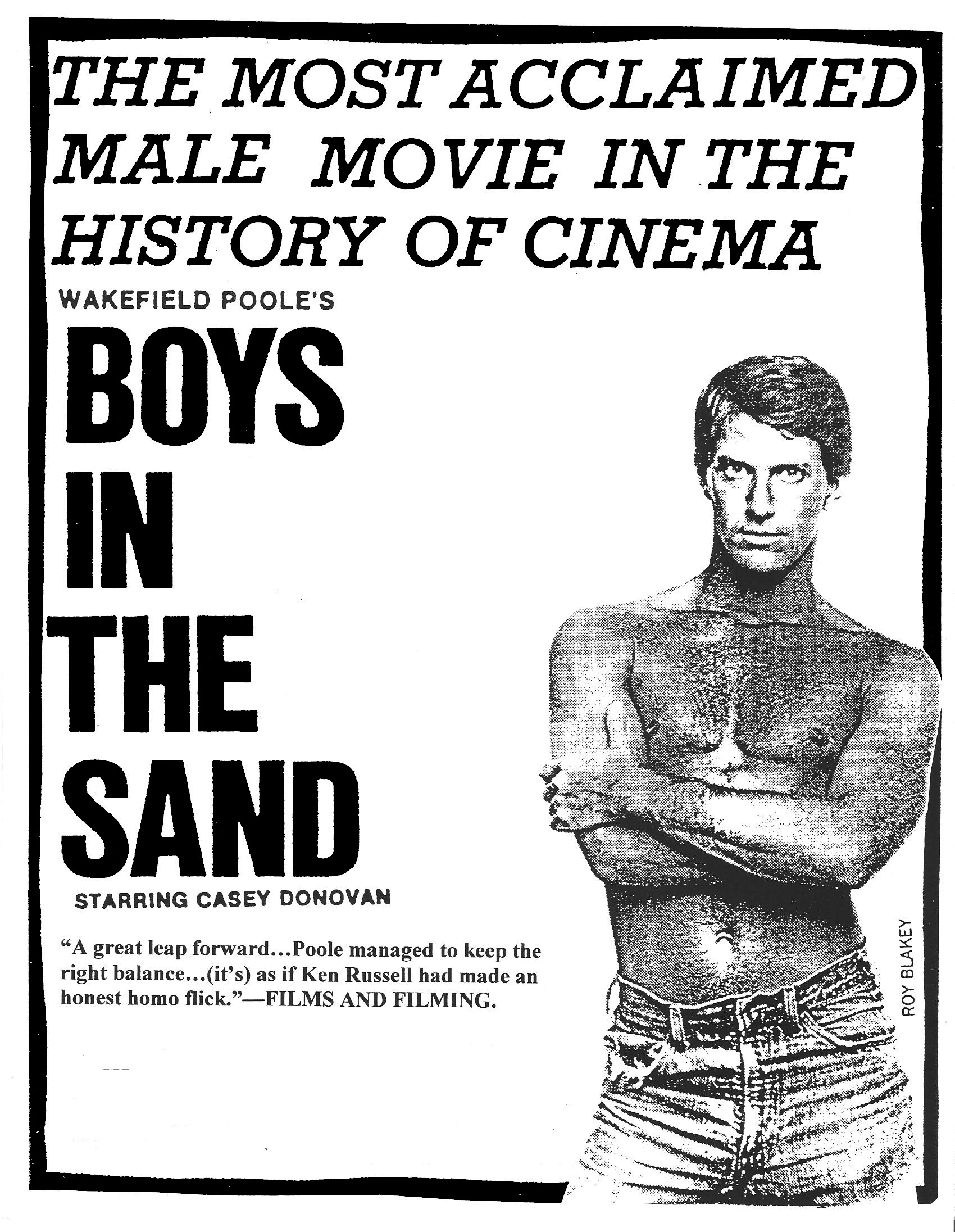

He sang as a child, danced for the Ballets Russes in the late ’50s, became a choreographer on Broadway, then started experimenting with film in the late ’60s, just in time for gay liberation. By switching his talents to making adult gay movies—a very risky thing to do in 1971—Poole created what is arguably the first commercial movie in this genre, namely Boys in the Sand, which was the first gay porno to be reviewed in Variety magazine and the first to achieve box-office success. Poole would go on to produce a number of other movies, notably Bijou (1972), Wakefield Poole’s Bible (1973), and Take One (1976), which are discussed at length below.

Wakefield Poole’s autobiography, Dirty Poole (2000 and 2011), was turned into a documentary called I Always Said Yes: The Many Lives of Wakefield Poole (2013), directed by Jim Tushinski. Wakefield Poole has always thought of himself as an artist whose films are but one form of creative expression. His other accomplishments need to be acknowledged, but even if we focus only on the “blue” movies, we find that they contain hidden gems and a subtle beauty that make them true “art films.”

Joey Rodriguez: What possessed you to create a film such as Boys in the Sand even while risking arrest and imprisonment?

Walefield Poole: I had seen a very poor gay film called Highway Hustler. And it was just a lewd film made with no money. A guy picked up another guy on a highway and held a knife to his throat and fucked him. I thought, “That’s so ugly. Why can’t they be beautiful? Why do they have to be in some seedy hotel with dirty feet?” You know, why can’t somebody make it attractive? And then about six months later, I did. I made it for fun just to see what it would look like to make a movie with pretty people who were clean, although they did the same things sexually. I brought into the film the idea that men could be proud of their sexuality and the things they do.

JR: The film also showcases the first appearance of cock rings, dildos, and the use of poppers to enhance sexual situations.

WP: Men felt that it was all right to do that. It was okay to be diverse. That’s why I had a black guy in the film. If you wanted to go with a black guy, okay, do it. I wanted them to be open sexually and not be afraid. I wanted them to do whatever they wanted to do as long as they didn’t harm anybody.

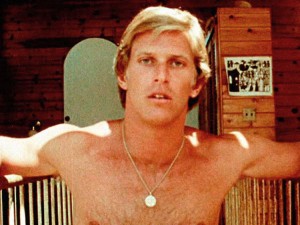

JR: You had to reshoot the first segment of the film because of a money dispute with the original actor by the name of Dino. How did you come to cast Cal Culver (aka Casey Donovan)?

WP: My friend Joe Nelson said, “Oh, I have the perfect guy for you. He’s beautiful and he just made a movie [Casey], and I think he’d be interested.” I met up with him [Cal] and showed him the scenes of Dino and my lover Peter Schneckenburger [aka Peter Fisk]. And he loved it. He said, “I’ll do anything you want.” And, so we expanded it and made it into three sections. And we became dear friends and stayed dear friends until he died. We made six films together.

JR: Did Cal ever confide in you on a personal level, or did you view him strictly in his Casey Donovan persona?

WP: I hate to say it, but he was born to be a porn star. He had the ego. He had the determination. I said it to him once when he started hustling and he made a lot of money because everyone wanted to fuck Cal Culver. [His ad in The Advocate stated that] he was every gay man’s dream. And that’s the truth. Everybody wanted to fuck with him. People called me up wanting to spend the night with him or hire him or whatever. I’d just give them a number to call. And he’d return their call. I had nothing to do with it. So he was able to make it work for him and make a lot of money and meet a lot of people. He was a school teacher originally. He led a very good life. And he was very grateful that I gave him the opportunity to have that life. And I was grateful to him for giving me the opportunity to make Boys in the Sand so successful. He was very much of a part of the success of that film, because he was every gay dream.

JR: Now you both are part of gay film history.

WP: Yeah, we made our niche.

JR: What’s the story and inspiration behind your second film, Bijou?

WP: Well, there isn’t much of a story except that after Boys in the Sand made a lot of money, I wanted to make better films. So I bought a new camera with the first profits from the film. My [business]partner [Marvin Shulman, cofounder of Poolemar Productions] bought a Cadillac, and I bought a new $10,000 16mm camera. That was a lot of money in those days. I decided I wanted to make a different kind of movie. I wanted it to be very abstract. I was very much into bathhouses and very much into multi-media at that time. I had done a couple of art gallery shows using multi-media. At first I was going to make that movie, and it was going to be straight. But then I decided, nah, I’m going to stick with my genre and make it gay. I’ll make it about a straight construction worker. I didn’t really specify that he was straight, though he had a Playboy calendar on his wall. So, I wanted to do a film about freedom, a film that would make people think about not letting fear keep you from enjoying new life experiences. And that’s the whole reason for Bijou.

The movie starred Bill Harrison. I hired him over the phone without ever seeing him naked. I didn’t know that he had an enormous dick. But I hired him from California. My [business]partner had met and fucked him and said that he was very good-looking and looked like Robert Redford. I said, “I’ll buy that.” We made Bijou in four days. I made it in my apartment in New York, which had a huge living room.

JR: I heard that you were a big success at the Berlin International Film Festival.

WP: It was inspiring. We did a retrospective. We sold out every performance. The biggest hit was Wakefield Poole’s Bible (1973), which was a big failure here in America. But in Germany they looked at it as a movie. It was my answer to Walt Disney’s Fantasia. It’s a story with an adult theme put to music, and the music is just as important as the picture. In the old silent movie days, before sound, people didn’t look away from the screen, because they’d miss some of the story. The story was told through expression and movement. So, they had their eyes glued to the screen all the time. That’s how I made the movie. Don’t turn away because you might miss some little, subtle thing. Some little gems that I put in—some people would get them, some not. I didn’t prepare anyone. Don’t come with any preconceived ideas. Just watch the movie and let it sink in.

Let me just say that Boys in the Sand and Bijou were very successful and very hardcore. I brought out the next movie [Bible] because I wanted to do the same thing for women that I had done for men in Boys in the Sand. I wanted to help the Women’s Movement. So, it’s all about the women in the Bible.

JR: I know you’re in the process of trying to change people’s perception of your work, so that people will think of you more as an artist rather than as just a pornographer.

WP: But once a pornographer, always a pornographer. I’ve always been that because I’ve always been treated like that for the last forty years. And, you know, even from my family. But they don’t hate me for it. My niece just said, about a month and a half ago, “I am so proud of my Uncle Wakefield.” In Germany, they saw how people looked at my films as experimental as opposed to pornographic. They considered the films they looked at to be avant-garde. Bijou was completely different from any pornography film ever put out there. I got noticed usually for artistic films.

JR: Fast forward to 1977, after a bit of a hiatus, and you are releasing a film called Take One.

WP: I made that in San Francisco. Men told me their sexual fantasies, and I made them real. It was like a docu-fantasy. I had two identical twin brothers [Rudy and Dutch] who had never made love to each other. They were both gay. They said that they wanted to have sex with each other. So, the first time they were together, I filmed it. But that was just one little section. Richard Locke, a very big porno star at that time, wanted to be photographed in the desert with his lover. So I went and filmed them on top of their little house out in the desert. That was his fantasy. I had another obsession where a guy had a convertible car, and he had it all redone and airbrushed the interiors so the seats looked like the original leather. So he makes it with the car. He ends up coming on the side of the steering wheel. I call [this film]my Chorus Line because they get up and do their solos.

JR: Why did you experience legal trouble with the film?

WP: Well, at that time I was about to bottom out on drugs. I was doing a lot of freebasing. This was 1978. We opened Take One in San Francisco, and it did wonderful business. And as business started to dwindle out, I did a live act with Roger, another porn star at the time. He was very hot—very big. And so, I put quite a bit of effort into doing a nightclub act with him. I took the film to New York, where it played at the 55th Street Playhouse. I had the run of the theater for four months. In ’71 the filmmakers who were making gay films, like Jack Deveau and Joe Gage and all my contemporaries, showed their films there and made a lot of money because we were doing it on our own and didn’t have any mafia guy ripping us off and giving just fifty dollars. Eventually, the theater was closed. Some of us stopped making films, and Joe Gage went off to do something else. Around that time the porno business had started to fade because VHS was coming in, so people didn’t want to go to the movies. We weren’t making money anymore. So, my business partner accused me of stealing. The film made a lot of money in San Francisco, but taking the film to New York City was a whole different story. I had all the paperwork and ticket stubs that I showed to the lawyer. Anyway, it has taken me a long time to get my film back.

JR: But why would your partner accuse you of stealing in the first place? Did it have to do somewhat with his knowledge of your known drug use at the time?

WP: That was partly the cause of it. But I would never steal anything. Why would I ruin my reputation? But they ruined the possibility that the film could play everywhere else in the U.S. It didn’t make any sense. They had expected that it would make money, like Boys in the Sand. They were in it for the money. And when they didn’t make $50,000 in the first week, they were upset. They decided that they’d take it out on me to cheer them up. So that’s what happened.

JR: Take One was re-edited before wide release, correct?

WP: I had made it when I was really into cocaine. But the film was very successful. There were only about ten gay theaters in the U.S. at the time. It played all those cities. We sold it on 8mm.

JR: Only ten theaters?

WP: There were a lot of hole-in-the-walls that showed 16mm. Trashy little places. But I’m talking about the next rung up. We were the first to get to go to these theaters and book ourselves in these theaters. That was in 1971. And with Boys in the Sand, because of its reputation, everybody wanted it. So we compiled a theater list and other filmmakers like Jack Deveau and Hand in Hand Films all used our theater list to book their movies. So, we sort of built the gay porno industry, my partner and I. I said that there were only ten theaters that made any money. The other theaters were making $250 all week long. Yet, they wouldn’t report it. They’d rip you off. Nevertheless, we did very well, and we made a lot of money in 1974.

JR: What did you find so alluring about the bathhouses?

WP: I don’t know how to say this, but the bathhouses were sort of like the first institutions that came at the right time for hedonistic people and people who enjoyed multiple sexual encounters and public exhibition, all of which took place in the shower, the steam room, the lounge room, and in private rooms. Again, it has all to do with freedom and fear. A lot of people feared getting killed at bathhouses. I had a lot of friends who were afraid and never went to one. I went to all of them. I wanted to get fucked in all of them. I was at the Continental Baths the night Bette Midler made her debut! I didn’t go in and see her because I was too busy fucking. My lover [Peter Fisk] had met somebody, and I had met somebody. We met downstairs and it turned out the person he had been with was the lover of the person I had been with! We became very close friends, and I was invited to Fire Island for the first time. And because of this I had the exposure to make Boys in the Sand. So, my life totally changed, like Bette Midler’s, that night.

JR: Younger people may view such establishments as passé or a sign of desperation.

WP: Well, it’s a different world now because of the health situation. Fortunately, I was there at the right time. I was able to have my “coffee with crème.” It’s a totally different situation now, but that doesn’t make me feel guilty that I had anything to do with the situation and the fear [that ensued]. But I feel that we lived in the best time to be gay.

JR: Why did you decide not to make any more films after the mid-1980s?

WP: I deal with fantasy. All of my films deal in fantasy. The minute you bring out a condom and put it on or you see someone else put it on, the fantasy is gone. It becomes real. I don’t care if they admit it or not, but at that moment they think about the disease and the situation. So I thought, well, I’ve done it, I made my mark, said what I had to say. The only thing I could do is repeat myself. So I choose a different career. I became a chef. I went to the French Culinary Institute and graduated. I went to work at a fine French restaurant in New York City. After that, I went to work for Jacqueline Kennedy. I worked for her for about five years. Then I went to work for Calvin Klein for fifteen years. And then I retired. I worked for Calvin Klein’s cosmetic company at Trump Tower. I made it again in a different career, but I did it my way. There are many things about me that you don’t see in the movie Dirty Poole.

Joey Rodriguez, a freelance journalist and multimedia artist, is founder-editor of the fanzine Libertine.