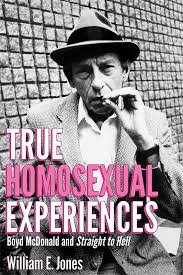

True Homosexual Experiences:

True Homosexual Experiences:

Boyd McDonald and Straight to Hell

by William E. Jones

We Heard You Like Books

220 pages, $25.

THINGS I WAS surprised to learn in William E. Jones’ biography of the legendary pornographer—or, in today’s terms, aggregator of sexual histories—Boyd McDonald: first, that he got the idea for his magazine Straight to Hell after reading a passage in Myra Breckinridge lambasting circumcision; second, that McDonald had a gay brother named Mark, an antiques dealer who lived with his male partner on the Upper East Side of Manhattan; third, that while studying at Harvard, McDonald lived in Eliot House—once, and perhaps now, the snobbiest of all the dorms—a year behind Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery; and fourth—a big surprise, given the meaty Caucasian farm boys with enormous schlongs whose images he sprinkled through his publications—that McDonald was, according to his editor at Christopher Street magazine, “a Rice Queen.”

The last point is not gone into, like most everything else about McDonald’s private life. So, first the facts: the Reverend Boyd McDonald (a mail order doctor of divinity) was born in 1925 in Lake Preston, South Dakota (population 599, Wikipedia says, with four registered sex offenders), where his father, after managing a garage, became a truck driver hauling grain, something Boyd did too for a year before being drafted by the Army and then enrolling at Harvard after the war. (Typically, his sole recollection of military life was a huge cock on a soldier from Vermont.) As a fellow student, John Ashbery found McDonald “colorless”—though he may have just been shy amidst the Eastern preppies, albeit not too shy to steal all the chairs from the Eliot House dining room one day and hide them in his room. Pranks he never outgrew; in later life, dining at his sister’s in New Jersey, McDonald would scramble the place settings and take his niece up and down the stairs whenever a certain commercial about the value going “up up up” and the prices going “down down down” came on the radio. He was charmed by little girls, especially his nieces.

At Harvard, he majored in American history and literature and took a course with the behavioral psychologist B. F. Skinner. Upon graduation he went to work for Time/Life, Inc., a job so against his grain that he began drinking. Alcoholism ran in the family, and McDonald continued to drink for the next two decades while working for one business magazine after another until finally, in 1968, he checked himself into a hospital on Long Island, got sober, went on welfare, and found a room in an SRO (single room occupancy hotel) on West 71st Street, where he remained until his death in 1993 of pulmonary disease exacerbated by a severe smoking habit. Last but not least—the reason we’re remembering him—while living in the SRO he founded a magazine called variously The Manhattan Review of Unnatural Acts and Straight to Hell: The New York Review of Cocksucking, the latter title a parody of a certain august intellectual journal to which, perhaps surprisingly, he subscribed, along with The New Yorker. But that shouldn’t be a surprise, since McDonald’s subject matter was never just sex—it was politics, movies, the world around him, and all its pretensions and pomposities.

O’Hara, Ashbery, and McDonald—three poets, each in his own way. Jones gives us examples of the sort of writing McDonald did for Henry Luce, including a moody portrait of a poor woman living in Natchez, Mississippi, which, effective as it is, cannot compare to his prose once he switched to the subjects of homosexuality and hypocrisy. The difference between the piece on Natchez and what McDonald wrote once he started Straight to Hell is the difference between a writer trying to conform and a writer who has found his voice. Here, for instance, is what he wrote about his former employer once he’d liberated himself:

[Time magazine’s] latest jackoff fantasy concerns a psychiatrist in lower California who gives therapy to “girlish boys” in hopes of … making [them]more butch. … “Left untreated,” Time warns, “most of them would grow up to be homosexuals.” Left untreated, many other boys grow up to bomb hospitals and orphanages in Southeast Asia, shove entrenchment tools up Vietnamese vaginas, bait “fags” on TV while aggressively looking for cock off-camera, peddle justice to the highest bidder in the Nixon administration, become sex-crazed cops who seduce homosexuals in shit houses and mug them when they accept.

The books that McDonald put out had titles like Scum, Filth, Raunch, Meat, Wad, Juice, and Lewd, titles whose aggressive smuttiness betrays an anger that was inseparable from his humor. McDonald was as livid as Juvenal, or, in our own time, Gore Vidal, or McDonald’s fans in Boston, Charley Shively and John Mitzel (both editors/cofounders of Fag Rag and The Guide). What the academics now call heteronormativity—heterosexuals and all their works—seems to have driven him nuts. In STH you were as likely to find a picture of Henry Kissinger picking his nose as you were of baseball player Pete Rose grabbing his crotch.

It is tempting to see McDonald as a man driven to do what he did by the culture of the 1950s. Not only did he work for Time-Life, Forbes, and IBM, but he did so at a time when William H. Whyte noted in The Organization Man (1956) that the soldiers coming back from the war seemed to have only one desire: to move to the suburbs, where they could raise a family in a safe environment. (Gay men would not want to do that for another sixty years.) After his attempt at conventional employment was sabotaged by his drinking, our Pervert in the Gray Flannel Suit found his vocation editing a porn magazine—though it was not porn he was purveying, he said; it was sexual history. This consisted of letters written to McDonald by men all across the country describing the sex they’d had. McDonald supplied headings for the letters that combined a deadpan objectivity with camp: “Youth Sniffs Dad’s Shorts,” “Airmen Fuck In Shower,” “We Kissed With Our Mouths Closed,” “I Wanted To Taste It,” “The Room Smelled Like Butt Hole,” “I Asked Him If I Could Touch It,” “He Told Me I Was Biting His Cock.” (The titles in “Great Moments in Journalism,” a column he wrote for Christopher Street, seem almost subdued in comparison: “Coach’s Sweat Rots Jackets,” “Sir Anthony and Parliament Member Cruised Toilets,” “Rowdy Romanian Pisses on Banquet.”)

It is tempting to see McDonald as a man driven to do what he did by the culture of the 1950s. Not only did he work for Time-Life, Forbes, and IBM, but he did so at a time when William H. Whyte noted in The Organization Man (1956) that the soldiers coming back from the war seemed to have only one desire: to move to the suburbs, where they could raise a family in a safe environment. (Gay men would not want to do that for another sixty years.) After his attempt at conventional employment was sabotaged by his drinking, our Pervert in the Gray Flannel Suit found his vocation editing a porn magazine—though it was not porn he was purveying, he said; it was sexual history. This consisted of letters written to McDonald by men all across the country describing the sex they’d had. McDonald supplied headings for the letters that combined a deadpan objectivity with camp: “Youth Sniffs Dad’s Shorts,” “Airmen Fuck In Shower,” “We Kissed With Our Mouths Closed,” “I Wanted To Taste It,” “The Room Smelled Like Butt Hole,” “I Asked Him If I Could Touch It,” “He Told Me I Was Biting His Cock.” (The titles in “Great Moments in Journalism,” a column he wrote for Christopher Street, seem almost subdued in comparison: “Coach’s Sweat Rots Jackets,” “Sir Anthony and Parliament Member Cruised Toilets,” “Rowdy Romanian Pisses on Banquet.”)

Not everyone is turned on by written porn, of course, but one could always just look at the photos in STH, which were much sexier than those in mainstream porn magazines like Mandate, Honcho, or Inches. McDonald had flawless taste in men—men one looked for in vain in Manhattan. (The guys in leather at the Eagle’s Nest were usually psychiatrists and decorators; the street kids in Times Square carried knives.) McDonald’s icons belonged to an era when men were not divided into homos and heteros but had sex with one another without thinking of categories, simply because, as he claimed, “Men are such dirty things.” When McDonald interviewed the photographer David Hurles about the subjects he found on the mean streets of Los Angeles, he asked, “Are the pricks you photograph naughty-but-nice types or are they authentic bastards?” and Hurles replied: “Most are real pricks and rotten bastards. I wish it were otherwise. … Being a prick is just not enough.”

The models in STH, however, are almost always smiling. They’re like the hayseeds in the old dirty postcards, lying in a barn with a blade of grass between their teeth—the male equivalent of the farmer’s daughter. The message is: come and get it! Reverend McDonald ran a church of cheerful sex. Though he had at least two nervous breakdowns and was suicidal more than once, the tone of STH is one of relentless uplift. The titles given the readers’ letters—“Maid Finds Dirty Underpants in Harvard Bedroom”—could have come from The Onion. Smile while you look at the camera, and give society the finger, since what is hanging between your legs is what everybody’s after!

As for the letters, the question almost everyone who read STH inevitably had was: were they authentic? Steven Greco asked McDonald that very question during an interview for The Advocate. McDonald got up, opened his closet, and showed him the sacks of mail. The only thing he did to edit them, Jones says, was get rid of repetitions. Otherwise, he wanted them just as they were written—unaffected, unliterary, even boring. “The letters I like are the ones that are pretty ragged,” McDonald said. “A lot of fears, and flaws, failures. The three Fs.” Jones writes: “The Straight to Hell contributors whose sex stories interested him but were lacking in specifics would receive questionnaires requesting descriptions of sights, smells, and tastes in extreme detail.” “I don’t want porn,” McDonald said, “but anti-porn.” Which still raises the question: did what the letter-writers describe actually happen? McDonald thought so. “These things in my books not only can happen, but did happen. It’s more exciting that something did happen, rather than some lone fiction writer imagines that it happens.”

The issue of STH that I have around the house is #53. (There is no date, as with Christopher Street when it began falling hopelessly behind schedule, probably for the same reason.) On the cover are two young men in jockstraps photographed by Christopher Makos, which suits this moment in STH’s history, since by that time it had been picked up, Jones notes, by the downtown art crowd: Warhol and John Sex, Jackie Curtis, and Taylor Mead. There were even, at that point, STH parties every Sunday night at the Pyramid Club, where men competed to be on the cover of the next issue. Inside are the sex histories. It is perfectly believable that McDonald had a closet full of letters—though later on he said they were drying up—but when you read the stories in Issue 53, a certain uniformity of style and content becomes apparent. McDonald disliked a “house style”—something that drove him to drink when he worked for Henry Luce—but these letters seem to be written in just that. Most feature adolescents. “I guess I was kind of sexy,” reads the first entry. “I had reached my full height of six feet by then and I was very muscular from lifting bales of hay and sacks of grain on the ranch. But I didn’t shave yet, was very shy and had a baby face despite my size and muscles.” It sounds like a combination of McDonald’s boyhood milieu and the pornographic fantasies of the era of the old posing strap magazines out of Los Angeles.

Whatever their truthiness, the collections of sex stories McDonald began bringing out, with titles like Scum, Meat, Raunch, Flesh, Wad, Smut, and Cum, sold thousands of copies. Gore Vidal was a fan of STH (“quite an imaginative little paper”). His magazine had even been mentioned, McDonald notes proudly in his short editorial in Issue 53, “in the Wall St. Journal, and, even more important, the NY Post.” Robert Mapplethorpe and Sam Steward were fans. When McDonald interviewed the latter, he was very direct: how much sex did they have, where did they get it, what did they like to do? However, he rarely said a thing about himself. Indeed, there’s surprisingly little here about McDonald—his relationship with his parents, his service during the war, his own sex life—which means much of Jones’ brief biography is perforce about other people, those who constituted the cultural context in which he operated: figures like Alfred Kinsey, Gore Vidal, John Waters, David Hurles, Susan Sontag (“Notes on Camp”), Fran Lebowitz (“Notes on Trick”), Louise Brooks, Gale Sondergaard (The Spider Woman Strikes Back), Barbara Stanwyck (whose working-class moxie McDonald loved), Katharine Hepburn (whose patrician air he despised)—even Sonia Sotomayor, who had to decide whether McDonald’s work was pornographic in a case in which a sex criminal was accused of violating the terms of his parole by reading Straight to Hell.

What McDonald would have made of Sotomayor we’ll never know. But authority figures seem to have had an irresistible attraction for him. That’s why, while watching an old movie called Stallion Road on TV simultaneously with his editor Tom Steele one night, he marveled at how fat Ronald Reagan’s ass was when the future president got onto his horse: “‘My God Almighty!’ I cried over the phone to a friend when I saw Reagan stick his big butt in the camera, and my friend, watching the picture on his own receiver 60 blocks to the south of me, released a simultaneous cry of astonishment.”

JONES’ BOOK, given the slenderness of the record, is almost more of a personal essay than it is a biography: a series of sidebars based on the topics McDonald inspires. Other figures Jones uses to flesh McDonald out run the gamut from Richard Burton (Anatomy of Melancholy) to Manuel Puig, Marcel Duchamp, Quentin Crisp, Diogenes, and British politician Tom Driberg. But McDonald’s family gets short shrift. He once said, “Somebody asked me, ‘How can you do this kind of work?’ and I said, ‘Because my mother died.’ You can’t integrate this kind of work with your family. … I wouldn’t want my family to see any of my work.” So we never learn what he thought about his upbringing, or why he stopped speaking to his gay brother. At one point Jones considers McDonald’s relationship to leftist politics: the socialists who were aware of his work were so disgusted by what gay men did that they wanted to have nothing to do with him. Jones has to reach back to ancient Greece to place McDonald in the scheme of things—to Diogenes the Cynic, who “when observed masturbating in the marketplace … said he wished it were ‘as easy to relieve hunger by rubbing the stomach,’ and told Alexander the Great, when the king asked the sunbathing philosopher to name whatever he wanted, ‘Stand out of my light.’”

But the real kindred spirit, it seems to me, is Richard Lamparski, the author of an eleven-volume series on film history called Whatever Became Of….?—a man “so crucial to American culture,” wrote McDonald, “that one no longer uses his first name, Richard.” Lamparski was “another elderly loner,” Jones writes, who “was in his way even more cantankerous than Boyd” and as obsessed with stars. (McDonald’s funniest writing, which is saying something, is arguably to be found in Cruising the Movies (2015), which collects his columns in Christopher Street under the same title.) In Jones’ view, both men became isolated for the same reason. They got old. Time did to the two obsessives what it had done to the actresses they revered. “The door would open,” Lamparski said about going to interview one of his actresses, “and I would think ‘Now is this her daughter, or is this her mother?’ Because they either looked ghastly or they looked wonderful. It was either one or the other, and it was the same with the men.”

McDonald and his brother were both quite handsome when young: clean-cut, sharp, Nordic-looking—a result no doubt of his mother’s Norwegian background. By the time McDonald was living on doughnuts, coffee, cigarettes, and supplemental oxygen, he still looked, according to Felice Picano in his memoir Art and Sex in Greenwich Village (2009), like Alfalfa in Our Gang: hair neatly plastered but weird—in short, like the man down the hall in an SRO. “Diagnosed with a severe anxiety disorder, agoraphobic, and obsessive-compulsive, Boyd could have been completely marginalized,” Jones writes, “but he … made his mental illness work for him.” What caused the psychological difficulties remains a mystery. But that works. The less information, the more McDonald remains a symbol of the anti-establishment gay artist—the anchorite in the SRO devoting his life to recording sex histories, much as Proust holed himself up in the cork-lined room to complete his novel. Both men even died of the same thing—dietary neglect, one might argue: Proust subsisted on coffee and croissants, McDonald on coffee and doughnuts—which must have made their lungs even more vulnerable to pneumonia. When Picano went to McDonald’s room to deliver a royalty check, he found nothing but the writer’s bare essentials—desk, lamp, typewriter—accessorized with blue oxygen masks placed around the room.

The gay movement in which Picano’s generation participated seemed to have no effect on the man whose collections of smut had earned him a royalty check: “My work is an alternative to the gay liberation movement, and to the gay press,” McDonald claimed. “The gay press has to be sexless because they are public. And in order to be publicly gay they have to be closet homosexuals. My books are all about homosexuality rather than gayness. … It has nothing to do with gay liberation, gay rights, gays in the military, civil rights, fundraising, political candidates, and all that stuff. If you’re going to be a lobbyist or lawyer running a fundraising campaign, you cannot be sexual. It is a necessity that the whole gay liberation movement had to give up sex in order to go public as gay.” As for attempts to solve the problem of homosexual old age, he was just as recalcitrant. When a friend took him to a SAGE meeting, he “didn’t like it because he said it was just old faggots.”

Still, one reason people are now looking back at McDonald (and Mapplethorpe and Samuel Steward), I suspect, is the yearning, now that gays can get married, for a more sexual, subversive past. In the age of assimilation, people want to be reminded of homosexuality’s underground roots. There was McDonald, our Venerable Bede, copying not ancient manuscripts but letters from readers describing blow jobs. He disliked the romantic concerns of the middlebrow gay press that flourished in the ’70s. It was, he said, “up to its ass in love, so I specialized in sex.” Sex with a certain type—the type that photographer David Hurles was wont to photograph and that was used in two of McDonald’s books, Meat and Skin. “I regard extreme and frequent sexual heat, and the obsessive, compulsive prowling of people who are seeking to relieve it,” McDonald said, “as admirable—as a gift. … In work and in sex … only people who are obsessed and compelled do extraordinary work and live extraordinary lives. They make ordinary people feel bad.”

As for why he chose sex, not love, Jones quotes McDonald on the course he took as an undergraduate with B. F. Skinner: “We weren’t allowed to use any of the words that everyone always uses like love. You couldn’t use any word that couldn’t be located during an autopsy on a body.” That last wonderful sentence may explain why sentimentality, nostalgia, and romance had no part in McDonald’s world: “Anatomy’s ‘truth of the body,’” Jones writes, “is incompatible with introspection.”

In real life, such devotion to the body can be frustrating. McDonald told The Advocate in 1981: “Recently I jacked off almost constantly for five days—except for when I went out for food.” In 1992 he confessed that his main sexual activity was “abusing myself.” But what else is an old man to do? He couldn’t afford hustlers, I assume, and after reading this biography, one wonders if he would have hired them if he could have. You wonder, too, what McDonald would have made of Internet porn. Jones says the Internet has destroyed everything—it has—but one thing it’s enabled is the consumption of pornography on a scale never seen before. We are all sleeping, on-line, with people we could never have gotten in real life. The problem is, this leaves us not only alone but perfectly well-behaved consumers, without any of the smells and butt hair that were the lesson of the Reverend McDonald’s church.

Or the humor. All of Issue 53 is funny: the sex histories, the interview with John Sex, McDonald’s editorial, in which “the consummate stay-at-home bore” confesses he has just spent a summer “so stupefying that I felt like Sunny von Bulow.” Although McDonald never imagined himself part of the art scene, it saw in his snarky send-ups a kindred spirit. He and the crowd around Warhol based their work on transgression; STH, you might argue, is the prose equivalent of Warhol’s piss paintings. Like Warhol, whose sense of humor has been underrated, McDonald was a consummate stylist. While ripping off the veil that hid the homosexual element in American life, he was also making us laugh. What really drove McDonald is as much a mystery at the end of Jones’ book as at the beginning. But it gave us a body of writing that is original, funny, and liberating.

Nothing, not even AIDS, made him doubt what he was doing. But he makes you recall that Santayana defined fanaticism as redoubling your efforts when the original goal has been lost. Straight to Hell raises the question: Just what was the original goal? Photographer Joseph Modica said McDonald’s politics might be summed up as “up with homos / down with hypocrisy.” To say what was forbidden—in other words, to tell the truth—was the mission, though using words like “mission” is no doubt something he would have hated. What he was above all was a writer, even at the end when the subject of his writing was only an idea, not an experience. In his last depression, he told Tom Steele that he was going to jump off the roof of his building. A doctor intervened, and he was hospitalized. But then, Steele said, “His writing stopped, and not long after, so did his life. I’m afraid it was inevitable. His health was miserable, and he chain-smoked till the end.” He’s smoking on the cover of Jones’ biography.

Andrew Holleran’s novels include Dancer from the Dance, Grief, and The Beauty of Men.

Discussion1 Comment

Andrew Holleran’s Lewd article sent me to my bedside table. On the bottom shelf behind a crumpled electric heating pad I found McDonald’s Straight to Hell (Nos 39, 49,50, 51, 52) and his Cum, Skin, Filth, Cream, Smut, Scum, Meat, Flesh, and Rauch. They may explain why I served as the Lambda Lit web erotica editor for a couple years. It says more about my libido and the time I came out – the early 70s.

I was 28 married with a son when I came out in 1972. That year a thousand men from all corners of the country arrived in San Francisco every month to live free. We were a community of strangers bound by our pride in our sexuality (the faint-hearted went elsewhere). I had an active sex life that that didn’t stop me from occasionally enjoying a delicious erotic moment with one of Boyd’s stories of a farm boy in the big city or Navy man on leave on the bed next to me, with a worn pair of underwear (with holes even better) holding my genitals and a generous amount of my lube de jour for my hand.

Felice Picano and I were born the same year that makes me part of the Picano generation that Holleran alludes to. What characterizes Picano’s generation for me is: sex was my god. I loved sex with friends and I worshiped it with my partners; I indulged in sex with multiple partners at the baths. I experimented with different kinds of sex. I had sex with friends and partners on different drugs. I deprived myself of sex to see if it got better when I went back to having sex, and most important, I talked about sex. I talked about the sex we had last night, the best sex I ever had, the best sex ever with a certain man, the bad sex a friend kept having and the time I got caught by my father. Sex was second nature.

My generation believed we could change the world with love. When I arrived in San Francisco my generation had ended segregation in the South, we were ending the war in Viet Nam, and the women of my generation were asserting their claims for equality. Sex was my language and my religion. It kept me up late at night and fucking on the back porch at parties that always ended at eleven so the men could go to the bars. I thought gay liberation was the next logical step and once America had achieved gay equality America would become a just peaceful nation. But just as my world of love got even better than I’d hoped Reagan got elected and then AIDS took my beloved partner of eighteen years.

Like my generation the Millennials are out to change the world this time with technology. I wonder if they have our curiosity about sex and our willingness to test the limits of sex. Do they consider sex essential to sanity as we did? My heart would beat a little warmer if I knew another generation of gay men is going through life like the Picano generation did.