ON JUNE 4, 2013 the National Parks Service officially designated the Cherry Grove Community House and Theatre on Fire Island, New York, for listing on its National Register of Historic Places. This prestigious honor is considered of national significance, a rarely accorded designation in the National Register context and the gateway to future Landmark status. NPS highlights this site as being “eligible for the National Register under Criterion A in the areas of Social History, Performing Arts, and Community Planning and Development. The Community House and Theatre is exceptionally significant in social history for the enormous role it played in shaping what gradually evolved into ‘America’s First Gay and Lesbian Town.’”

The site becomes one of only three GLBT-specific National Historic Places in the United States. The other two sites are the 1999 National Register and Landmark listing of the Stonewall Inn in New York City’s Greenwich Village, and the recent listing of the Frank Kameny House in Washington, D.C. (Kameny organized the first gay rights demonstrations in Washington and Philadelphia in the mid-’60s.)

APCG 10th Anniversary Journal

These sites are the beneficiaries of scholarship carried out over the past two decades devoted to recovering and documenting gay and lesbian lives of past eras, however hidden or coded their interaction. While substantial background material beginning in the 1960s was produced in support of the Stonewall Inn and Kameny House, Cherry Grove’s listing breaks new ground by providing a historic link to our nation’s gay and lesbian lineage beginning in the 1920s. The National Register’s documentation specifically notes that the site “is especially significant because it offers the rare opportunity to document an entire community in the pre-Stonewall era.” The N.R. application further reveals that “the Cherry Grove Association’s ‘Art Project Committee’ facilitated what can be described as the first (1948) ‘gay theater,’ continually produced by gay people, for gay and straight audiences in the United States. The theater is also exceptionally significant for its association with homosexuals’ heightened visibility in the performing arts.”

Seaside resorts experienced international growth by the turn of the 20th century. Resorts were facilitated early on by the development of national rail systems that provided urban dwellers and locals alike with access to a new type of entertainment—beachside holidays. Steam and sail boats transported cottagers and tourists to the beaches at Fire Island on the final leg of their journey from the mainland. A restaurant and a hotel—a later (1880) addition, the Cherry Grove Hotel—were established by Archer and Elizabeth Perkinson in 1868 in a cherry grove on Fire Island Beach, the name of one of the barrier islands off the coast of Long Island. By the 1920’s the beach and hotel in Cherry Grove were an advertised holiday destination. Fire Island’s relative isolation, lack of a police force, and infrequent visits by the Coast Guard attracted a crowd of thirsty newcomers during Prohibition. New York City’s gay demimonde from Greenwich Village speakeasies, downtown and uptown cabarets, and theater and opera lobbies whispered of the natural delights to be discovered in Cherry Grove, and many found a relatively safe harbor where they could be themselves.

The Great Depression halted beach holidays for most, and the 1938 Hurricane destroyed much of Fire Island’s tourist industry and infrastructure, including Cherry Grove. Only 14 buildings remained standing there on a desert-like island swept clean of all greenery and most recognizable landmarks. The hotel survived, however, and in an economic compromise, born of a desperate need for financial recovery, some established (heterosexual) Grove businessmen and cottage-owning landlords engaged a new breed of tourists and renters. They were the gay and lesbian corporate and theater professionals from New York City, and their international guests, who could still afford the $100 plus rentals for a summer vacation in Cherry Grove.

Arts Project of Cherry Grove Archives

Being a beach-oriented colony, Cherry Grove’s early property owners, both straight and gay (albeit often closeted), adopted the custom of Sunday evening meetings after guests and day visitors had departed for the mainland. They met at the hotel (now called Duffy’s Hotel) to discuss and decide upon the course of growth for the community. Grove property and business entrepreneurs extended boardwalks into undeveloped tracts, acquired real estate lots for future cottages and businesses, and funded construction of its public dock, lifesaving equipment, medical services, and a fire department. Grove-elected officials grew local businesses: a post office, a grocery store for essentials, a restaurant, bottled gas and kerosene stations at the bay front. Wells were dug for water.

Cottages that had been swept into the bay during the 1938 Hurricane were pulled back onshore, restored, and enlarged. Grove property owners and cottage renters were the first among all Fire Island communities to replenish and nourish their dune system each summer following that devastating storm. The dunes were reseeded with grass and snow fencing by volunteers to protect the colony from future storm surges. During World War II, a small group of locals from Sayville, Patchogue, and professionals from New York City began the slow rebuilding of Cherry Grove. An artist colony established itself in the Grove during summer months. The board members of the Property Owners Association (POA) established working relationships with local and state agencies to further meet the needs of its seasonal residents. One could say that they grew a town on a sandpit.

Cherry Grove’s reputation as a holiday destination—for homosexual men in particular—began to spread far and wide. In her groundbreaking book, Cherry Grove Fire Island: Sixty Year’s in America’s First Gay and Lesbian Town (1993), Esther Newton described it as “a ‘gay utopia’ hidden from view of the heterosexual world. … Gay theater people’s migration to Cherry Grove is one of the clearest proofs we have that sexual preference was becoming [by the late 1930s]the basis for a complete social identity.”

Celebrated Grove founders and vacationers during the 1930s included Noël Coward, Christopher Isherwood, and W. H. Auden. Also: from the silent movie era, actresses Pola Negri and Nita Naldi, who attended the Cherry Grove community house fundraising events as guest stars; Glen Boles, a Hollywood movie star of the ’30s; journalist Janet Flanner with her lover Natalia Danesi Murray; and artist Paul Cadmus. By the 1940s, Cherry Grove was frequented by Broadway theater professionals, including Miles White and Oliver Smith, the well-known costume and scenic designers, the world famous composer Benjamin Britten with his lover, the tenor Peter Pears, and Lincoln Kirstein, a co-founder (with George Balanchine) of the New York City Ballet (1948). To homosexuals in cities around the world, Cherry Grove was known as an established residential community with a significant homosexual population.

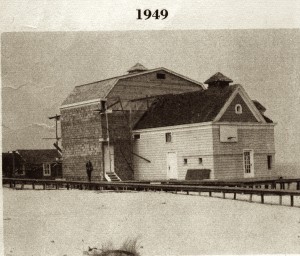

Earl Blackwell, Jr. and his partner Ted Strong, creators of the Celebrity Register, promoted the purchase of a community house at a meeting of the POA. The beach colony’s community house began its life as a small carriage house, purchased in Sayville, New York, and floated across the Great South Bay in the fall of 1945. Quickly winterized, renovations began in 1946 and town hall meetings were held on its surrounding decks that season. The entire community, straight and gay, joined creative forces raising thousands of post-World War II dollars to improve the building by holding carnivals, raffles with entire beach lots and a sailboat as prizes, square dances, and many crafts and bake sales.

Courtesy Lillian Bassman & Paul Himmel,

© 2013 Bassman Himmel Studio

On a Sunday in September, 1948, the membership of the POA created “an Artistic Activity Group for the benefit and entertainment of the entire community … to use and encourage the talents and interest[s]of all property owners, their tenants and their guests.” In less than two weeks, the Art Project of Cherry Grove presented its first production, The Cherry Grove Follies of 1948, a traditional vaudeville-style revue, in the tiny carriage house. The production was made possible when a section of the building was partitioned off with a curtain on a clothesline that created a “stage” and space on the outdoor decks for actors’ “dressing rooms,” shielded from view with sailcloth. Lighting arrived courtesy of a cable that was run from Duffy’s Hotel, the only establishment with electricity in the Grove at that time. A piano and a portable record player were moved from the hotel to the community house for music accompaniment. Live theater was practically nonexistent on Fire Island and absent from many mainland towns in 1948. People came from neighboring Fire Island communities or traveled by special ferry across the bay to the “Cherry Grove Playhouse.” Three shows on a September Saturday night, including a midnight performance, ran back-to-back to meet local and mainland audience demand. Blackwell announced $666 in ticket sales from over 240 patrons at Sunday’s property owners meeting.

The Cherry Grove Follies of 1948 featured the Broadway actress Bertha Belmore backed by a chorus line of Grove “boys” in tuxes, and Mabel Guerin, a Grove resident, in a sketch title, “Cherry Grove, 1910,” with a rendition of “Oh, You Beautiful Doll.” Norman Ruvell (a merchandising director for a NBC radio give-away show) was the soloist in a sketch titled “The Girl in the Song,” featuring another Cherry Grove mover and shaker, Kay Guinness. Bertha Belmore, 62, who was heterosexual (and President of the Art Project in 1950), boasted a professional theater biography that was both extensive and international in scope.

The speed of production and astonishing success of the nascent theater company’s first effort was due entirely to a prestigious cohort of consultants and participants from America’s legitimate theater, full-fledged homeowners or renters in the Grove community. Among these personages in 1948 Cherry Grove were Frank Carrington, founder of the Paper Mill Playhouse in New Jersey, and producer Cheryl Crawford, who brought Brigadoon, Porgy and Bess, One Touch of Venus, and Paint Your Wagon to Broadway. Also contributing their talent were: Marcella Swanson, Broadway actress and wife of Lee Schubert, the producer and theater owner; Carson McCullers, author of The Member of the Wedding; and George Freedley, founder of the Theater Library at the New York Public Library, who became a resident director of future Art Project shows. Broadway celebrities included Peggy Fears, a former Ziegfeld Follies star, and Hollywood film stars Betty Garde and Nancy Walker. Extremely talented residents were given solo spots or joined the chorus or chorus lines for clever musical sketches. Many more Grove residents volunteered their time and talents.

No community theater could be built solely from cigar box donations, however, nor with proceeds from three shows in front of a clothesline curtain, even in 1948. So, during the off-season of 1948, the POA, its Art Project Committee members, and their guests, raised additional theater building funds by hosting two parties at Spivy’s Roof in New York City. George Chauncey in Gay New York (1994) described Spivy as “an enormous lesbian, famous in the elite gay nightclubbing world. … A singer with a gay following.” Her nightclub was “one of several elite night clubs heavily—but covertly—patronized by gay men and lesbians.”

The sponsors’ journal for “The Roaring ’20s Party” included a story about the Art Project of Cherry Grove’s creation, titled “A Sunday in September.” The Art Project’s first fundraiser, a “Halloween Costume Party” on October 31st, “drew capacity attendance. Dick Avedon was on hand to photograph everyone in costume. You’ve never seen such magnificent pictures and Dick is turning over to the Project all of the revenue from the sale of the photographs.” Richard Avedon and his first wife Doe rented Pride House (still extant) in Cherry Grove with another couple for several summers in the late 1940s. The couple, Avedon’s close friends and colleagues Lillian Bassman and Paul Himmel, a husband-and-wife team who were fashion and documentary photographers for Vogue and Harpers Bazaar, would photograph the Cherry Grove Follies of 1949, the production that inaugurated the new theater at the community house. The only extant photo from that Halloween party is of the Cherry Grove Theater’s director, George Freedley, costumed as “Artaud” from Hamilton Forrest’s opera Camille (1929). The image was authenticated as an Avedon original in 2012 by curators of the Billy Rose Theater Division of the NYPL at Lincoln Center and The Richard Avedon Foundation.

The years 1948, ’49, and ’50 constitute the most historically significant period that contributed to creating Cherry Grove’s international reputation. The new theater addition was ready for its inauguration in June 1949. The advent of “gay theater” in the U.S. was brought to life by members of the legitimate American theater who formed “an organized performing arts network,” according to Kimberley Harbin, Bell Marra, and Robert A. Schanke in The Gay & Lesbian Theatrical Legacy (2007), which was “sustained through shared queer lifestyles and æsthetics, along with shared financial interests.” During these years a cross-section of international, national, and New York City-based heterosexual and homosexual actors, musicians, playwrights, artists, photographers, and poets discovered the joys and personal freedoms that could be experienced only in Cherry Grove.

These professionals lent their talents to the Cherry Grove theater’s development in the hope that it would come to rival the Provincetown Playhouse, which was located (oddly enough) at New York University in the West Village. To this end, the Art Project went on to produce Broadway-influenced musical theater revues in Cherry Grove during the summer months in subsequent years. These shows were routinely reviewed in local papers of the time, such as The Suffolk County News and Patchogue Advance, and in New York City theatrical news columns, including those of The New York Herald Tribune and the N.Y. Morning Telegraph’s “Off Stage—and On” column (not coincidentally under the byline of George Freedley).

The POA (today’s Cherry Grove Community Association, Inc.) held its annual meeting on the third Sunday in September. At these meetings the community witnessed and responded to attempts to purge the Grove of “undesirables” fueled by scandal-mongering newspaper reports about the murder of a gay boy by his jealous lover in Cherry Grove (1949); the firing of gay and lesbian federal employees and their harassment in the performing arts in Hollywood and New York City during the HUAC hearings chaired by Sen. Joseph McCarthy; routine entrapment and arrests stemming from police raids on Fire Island beginning in 1953; the exercise of their earliest civil rights by employing the ACLU to stop those raids in 1968. They developed an early gay/straight lobbying group to defeat Robert Moses’ plans for a highway down the center of Fire Island, and they created the Fire Island National Seashore with other beach communities in the mid-1960s. They accommodated the emergence of straight women and lesbians as business and home owners, as officers of Grove civic organizations, and as firefighters in the Cherry Grove Volunteer Fire Department. They weathered peeping toms, physical assaults, and a pyromaniac during the “anything goes” era of drugs, sex and disco, and survived as a community united in the face of the AIDS crisis of the 1980s.

The National Register application concludes with this statement of significance:

The Cherry Grove Community House and Theater’s greatest national historic significance lay in providing a socially secure and creative home for the Grove’s talented homosexual residents and their guests. It became “their” space, with a pride of possession literally forbidden to them in the nation’s public town halls, theaters and nightclubs of the era. Through their full participation in Grove community governance and theatrical entertainments, gay men and lesbians could be themselves, and as Amy Hoffman reminds us in “Do Tell: Recovering our GLBT History” from The Gay and Lesbian Review Worldwide [Jan.-Feb. 2013], “to find one another, and to affirm [their]existence and participation in society to the rest of the world.”

The Arts Project—its Broadway talents and camp humor—created a permanent venue on the Grove stage for gay creativity and self-affirmation. Together with the POA, it developed a revolutionary model for a community’s gradual acceptance of its gay residents, with all their individual modes of self- expression, long before the dawn of the Stonewall era. This earliest coalescing of two groups—gay and straight homeowners with widely divergent lifestyles—around a Fire Island community house and theater ultimately produced the nation’s first gay summer theater in America’s first gay town: Cherry Grove, New York.

Carl Luss is a legal assistant at Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, counsel to the Cherry Grove Community Association, Inc. As a volunteer for cgcai, he researched and wrote the nominating application for NYS Parks/National Register of Historic Places.