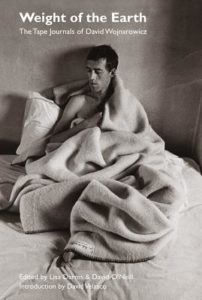

Weight of the Earth: The Tape Journals of David Wojnarowicz

Weight of the Earth: The Tape Journals of David Wojnarowicz

Edited by Lisa Darms & David O’Neill

Semiotext(e). 184 pages, $16.95

DAVID WOJNAROWICZ made art that marries an inner world of sadness, anger, and loss with an external world of natural beauty and human destructiveness. His life was bracketed by abandonment and abuse as a child and, in later years, by the emotional and physical toll that hiv/aids exacted before he died at 37 in 1992.

In his teens, Wojnarowicz was selling his body to pay the rent and buy drugs. He began writing and making art at an early age and continued doing it feverishly for as long as he had the strength. Through drawings, photographs, collages, paintings, writings, music, and more, he doesn’t flinch from confronting homophobia and, with the onset of the AIDS epidemic, from calling out the hostile cultural climate, the invisibility and neglect of the queer community. This is the Wojnarowicz we mostly know: the artist as warrior.

In 2018, the Whitney Museum mounted a major retrospective, David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night. The Whitney show demonstrated the extraordinary range of his accomplishments in so many media. And now, in Weight of the Earth: The Tape Journals of David Wojnarowicz, we see the artist as vulnerable and self-questioning. For two periods in his life, 1981–’82, and 1988–’89, he ad-libbed into a tape recorder touching on topics such as life in the city versus living close to nature, the distractions that interfere with artistic output, sensitivities about art as self-revelation, the dangers of art-world acclaim, loneliness and isolation, sex as a positive force or as an addictive drug, the elusiveness of intimacy and love, fear of “The Virus,” and fear of dying.

Woven throughout these tapes, which have a novelistic flow, are dream descriptions. For Wojnarowicz, the dream state holds as much credence as consciousness: “In a dream you can do anything—from fly to create horror to create pleasure to create incident to create weaponry to create repair.” Although the city shaped him as a gay man and an artist—hustling as a teenager in Times Square, frequenting the Chelsea piers and cavernous East Village bars and makeshift art galleries—Wojnarowicz is often dissatisfied with this ghettoized world and longs for the country: “I like the woods, I like landscape. … I love the sense of light and the sense of sound and the sense of space. … And those are things that nobody ever talks about here [in New York].”

In the 1981–’82 tapes, Wojnarowicz says he makes art “to make sense of my life,” but that he also craves “an emotional strength” that art can’t provide. He has no trouble scoring—“I find myself having sex a lot with men that are desirable, but I never see it beyond that moment.” But a fling in the park near 15th Street turns into something more. He goes home with Bill and they talk through the night. The artist, then 26, has lately been “withdrawing from most people because I don’t share their view of living, or their cynicism … whether it’s drugs or general drunkenness or a lack of motivation to do or make things.” He senses that Bill is “in touch with things that no other people I knew were in touch with,” and he sees the promise of a relationship. “It gives you a kind of strength, loving somebody or wanting to love somebody,” he says expectantly. Over time, though, it’s clear that Bill hasn’t been truthful and that he doesn’t want to commit himself to Wojnarowicz. The relationship ends on a note of disillusionment.

In the 1981–’82 tapes, Wojnarowicz says he makes art “to make sense of my life,” but that he also craves “an emotional strength” that art can’t provide. He has no trouble scoring—“I find myself having sex a lot with men that are desirable, but I never see it beyond that moment.” But a fling in the park near 15th Street turns into something more. He goes home with Bill and they talk through the night. The artist, then 26, has lately been “withdrawing from most people because I don’t share their view of living, or their cynicism … whether it’s drugs or general drunkenness or a lack of motivation to do or make things.” He senses that Bill is “in touch with things that no other people I knew were in touch with,” and he sees the promise of a relationship. “It gives you a kind of strength, loving somebody or wanting to love somebody,” he says expectantly. Over time, though, it’s clear that Bill hasn’t been truthful and that he doesn’t want to commit himself to Wojnarowicz. The relationship ends on a note of disillusionment.

During this same period, Wojnarowicz describes being in a bar with photographer and close friend Peter Hujar, who undoubtedly had the greatest influence on him as an artist. (“Everything I made, I made for Peter,” he once said.) In assembling his drawing portfolio, he questions whether he should get rid of the ones that are “aggressive or upsetting.” As reflected in the journals, the artist sometimes wonders if potential friends or lovers will be turned off by his art. Hujar’s advice is clear: “I shouldn’t start compromising and trying to adapt to other people’s taste.”

Six years later, in November 1988, Wojnarowicz begins to record again. He has recently been diagnosed with AIDS-related complex (ARC). He had helped care for Hujar, who died of AIDS in late 1987, and he is living in Hujar’s loft. He knows the virus may kill him too. His tone is heavier, reflecting not only his anxiety about getting sick and possibly losing his mind, but also the shock of realizing he’s getting older and less desired: “Just standing on a street corner … waiting for the light, and just seeing young man after young man. I mean, most of them probably in their early twenties, mid-twenties, and all of them very beautiful in one way or another.” Watching his youth pass and a sense of foreboding coincide with a growing bitterness about the art world. His work isn’t getting the sold-out reception it once got. Still, what he values most is art making that isn’t driven by the marketplace: “That’s what I love about when people make things: I love that they just do it,”

Recognizing both the possibilities and limits of language, Wojnarowicz sees taping as a double-edged sword. “I just can’t stand my self-consciousness when I talk into this thing.” He’s also afraid of “someone witnessing this tape.” Nevertheless, “if I keep talking into it, I lose the self-consciousness and I can just do it and get at stuff that’s deep underneath all this.” For Wojnarowicz, excavating the self to repair the self is the essence of the creative enterprise.

In the winter of 1989, with so many of his friends gone, New York is “just a city of death.” He flies to Albuquerque to begin a ten-day road trip, seeking solace in the Southwest, whose deserts, mountains, and open sky he finds “absolutely embracing” and “frightening.” “Yeah, I’m alive, but … I could be dead another year from now. And I won’t see this road, and I won’t see the sunlight, and I won’t see these fast trucks driving by—the long, long road up ahead of me, and a long, long road in the rearview mirror.” Driving along, with whatever music is on the radio, he’s thinking of “people like Peter … just knowing that he’s never gonna hear this song.”

Wojnarowicz returns to the city, but he’s off again in May, this time driving a friend’s car to L.A. Crossing Arizona, “everything arrives at that low tone of color, where it’s no longer fighting the sun for its color or fighting against the sun to show its color.” He stops at a rest station to look for a drinking fountain: “A few silhouetted cactuses and a bunch of bees trying to drink some water. … A couple of them were jerks. They fell in and drowned, but I pulled a few out that were still struggling.” In such moments, Wojnarowicz wishes “it could stay like this for maybe a few years, or I just never moved out of this spot. I could just watch the light stay like this. And maybe somebody coming along and just putting their arms around me for a few minutes.”

James Cassell is a painter and visual arts writer who lives in Silver Spring, Maryland.