IT TOOK MANY YEARS before I was willing to visit the city that declared itself in 1943 to be judenfrei (free of Jews): the city of Berlin, the capital of Nazi Germany. For me as a Jewish lesbian, Nazi atrocities must never be forgotten. But at some point I was invited to spend a fun weekend in Berlin to experience LGBT Pride, and the city was going all out to celebrate its historically persecuted yet resilient queer population.

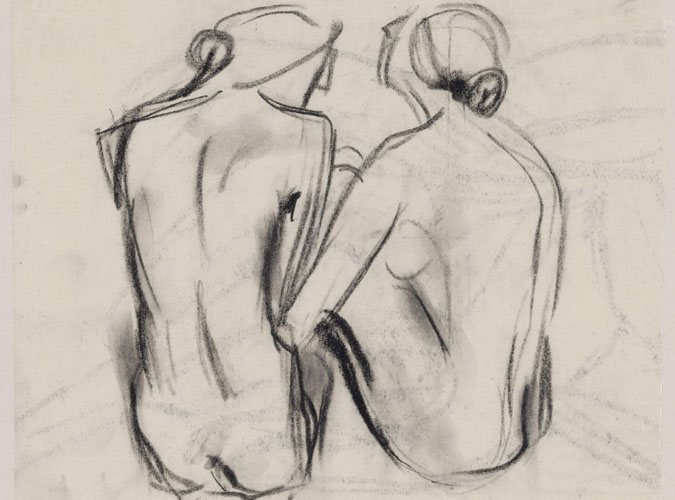

Among the Berlin Pride festivities that year (2013), there was going to be a special exhibition of 20th-century gay German artists, including Gertrude Sandmann (1893–1981). A few years earlier, London had hosted a major retrospective of avant-garde German artists during the Weimar Republic period, which spanned the years from the end of World War I to 1933. I adored one drawing of two nude women by Gertrude Sandmann. I had never heard of her, but learned from the brief caption that she was an important Berlin artist, a Holocaust survivor, a lesbian, and trailblazer of LGBT rights. By traveling to Berlin, I would discover considerably more, and so I set my reservations aside.

It was only a short plane trip from London to Berlin, a reminder of how quickly fighter planes and bombers could reach across the small checkerboard of Europe. On the night of November 22, 1943, the most devastating air raid since the beginning of the war began over Berlin. Six hundred British and Canadian airplanes dropped thousands of explosive and incendiary bombs on the city for two hours. Gertrude Sandmann crouched under a desk in her hiding place away from the windows, held her breath, and hoped that the bombs would not find her. At the same time, every attack by the Allies was bringing her closer to the liberation she so desperately longed for.

According to official records, in 1943 Gertrude Sandmann no longer existed. The other Jews had either fled or been murdered. But Gertrude Sandmann, who was of Jewish descent, was still alive in Berlin. Her brave non-Jewish lover and their friends had hidden Sandmann illegally. “Will they find me, or won’t they?” Sandmann kept asking herself until the war ended.

At the Berlin exhibit, each artist was introduced by a black-and-white self-portrait. I smiled up at a photo taken in 1960 of a white-haired woman in a painter’s smock standing confidently before her easel in a studio overflowing with drawings. Before her was an almost completed portrait of a woman wearing a hat. She reviewed it with a critical eye and presumably made a few final strokes. The artist was Gertrude Sandmann.

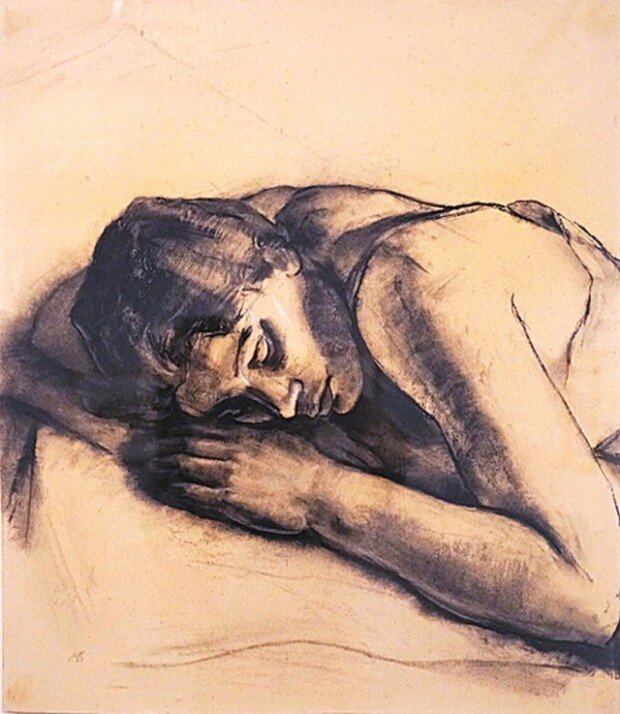

Despite being banned from her profession during the Nazi years, Sandmann produced well over a thousand works over her sixty-year career. The Nazis destroyed much of her œuvre as an example of “degenerate art.” She drew with chalk or charcoal and painted with watercolors and pastels. Form was the principal element for her, color an afterthought. She worked with omissions that were meant to stir the imagination, the viewer’s capacity to see. Her drawings made visible the unassuming beauty of everyday life that she discovered in a sleeping woman or a burst chestnut. Her artwork was the product of her joy in seeing, not a means of social criticism as it was for some artists (such as her friend Käthe Kollwitz). Her drawings are predominantly of women. Several nudes showing pairs of women have been preserved from the period around 1925. It is truly remarkable how Sandmann was able to grasp their essence and create an erotic atmosphere with such sparing use of materials and a few powerful strokes.

Gertrude grew up in Tiergarten, a well-to-do district of Berlin, in an assimilated Jewish family. Her father was a businessperson as well as a civil deputy. In 1913, Gertrude studied at the art school of the Berlin Association of Women Artists (women were not allowed in the national academy until after World War I). Other members of this still existing association included Kollwitz and Paula Modersohn-Becker. Throughout her career, Sandmann was very vocal about the professional discrimination of women artists. Sandmann joined gedok, the German-Austrian Society for Women Artists and Friends of the Arts, founded in 1926, and became a member after it was revived in the 1960s.

Gertrude Sandmann discovered rather early on that she felt “closer to women than to men.” At the beginning of World War I, she had a secret relationship with a girlfriend and fellow student. To satisfy the demands of her family and retain their financial support, she married a physician in 1915, but the marriage, in name only, ended in divorce after only a brief time. She wrote: “It is necessary or at least favorable for a woman artist not to live in a union that makes demands of her in the sense of a patriarchal role allocation; instead, she should have a union that neither impedes her work nor hampers her development, that is, one containing much that is reciprocal and companionate. This is why it seems lucky to me if a woman artist is a lesbian and if she can declare this without feelings of guilt.”

Starting in the mid-1920s, Sandmann worked for an extended period as a freelance artist in Paris and Italy, participated in several art exhibitions in Berlin, and did illustrations for magazines to earn a living. In 1976, she reflected on what life was like for Weimar Republic lesbians: “If they wanted to live according to their nature, and not in the closet, they faced severe resistance, confrontation, pressure from family, and hiding their lesbianism in most occupations.” Despite everything, she was successful and independent during this period. She joined the left-wing Independent Social Democratic Party while studying in Munich, since it was the only party that had voted against the war.

In 1933, she quickly recognized what the Nazis coming to power could mean for her and her artist friends. She fled to Switzerland but had to return to Germany in 1934 when she was unable to extend her residence and work permits. In the same year, she was expelled from the national professional association of artists because of her “non-Aryan” heritage. In 1935, every artist of Jewish lineage, every political radical, and every gay person was banned from teaching, exhibiting, or selling their artistic works. Sandmann became dependent on her inheritance from her late father. In secret, she continued to draw.

By a twist of fate, Sandmann’s sister became an Italian citizen through her marriage to a non-Jewish Italian man. She registered their parents’ Berlin house in her married name in 1939 to save the family from losing it through “Aryanization,” as the Nazis referred to the expropriation of Jewish-owned property. Until 1942, the house provided Sandmann and her mother a place to hide. Sandmann had an opportunity to flee to England in 1939, but she could not leave her sick mother behind. She was still stuck in Berlin after her mother died.

As of September 1941, she had to wear the Jewish star, which made her more visible as an outcast and subjected her to abuse on the street. She was required to hand in all valuables. Only her bad health saved her from having to perform slave labor. In the summer of 1942, her only uncle and aunt were deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp and murdered.

In November 1942, Sandmann was threatened with “deportation”—i.e., being sent to a concentration camp. She decided to risk going underground. She fled her own apartment on November 21, 1942, leaving a note announcing her suicide to the Gestapo, who appeared at her door shortly afterward and stole everything. Suicide was an act of desperation not uncommon within the Jewish population. To make it look believable, Sandmann had to leave behind everything in the apartment, including her food rations card, which was necessary for survival.

Without the support of the friends who helped her while risking their own lives, she would not have been able to survive underground. Sandmann was lucky. Her partner, Hedwig Koslowski, an artisan who had been her lover since 1927, did not abandon her. Hedwig arranged a hiding place with friends of hers who were living in the Treptow district of Berlin. She remained hidden in a tiny closet and lived on whatever they could spare from food rations. The Diary of Anne Frank vividly described what it was like for Jews to live in hiding for months or even years.

Like Anne Frank, Sandmann had to avoid making any sound whatsoever in the poorly insulated apartment. She could not stand near the window nor ever leave the apartment, even during the heaviest of bombings, which left her utterly helpless. By the summer of 1944, this situation had become unbearable, so Hedwig found her a new hiding place in an unoccupied summer house in Biesdorf on the outskirts of Berlin. To avoid tipping off the neighbors, she was not allowed to start a fire or turn on any lights. Hedwig and another friend supplied her with food. Since she was not able to draw for long stretches of time, she recited poetry to herself, training her memory to stay sane.

In the fall of 1944, she had to move again because of the cold. This time Hedwig took her into her own apartment, which she shared with another artisan in the Schöneberg district. This is where Sandmann was living, emaciated at seventy pounds, when the Allied troops liberated Berlin. She was one of only 1,200 other Berlin Jews who survived the war underground. She had serious health problems caused by the conditions of her life in hiding. A small financial compensation for the injustices she had suffered during the Nazi period secured a modest existence for her. With the help of her partner, Sandmann soon found an apartment and studio in the Schöneberg district, where she lived until her death in 1981.

Shortly after the war, she started drawing again. Although she participated in several postwar exhibitions—in 1949, 1958, and 1968—only in 1974 did she receive significant acclaim at a solo exhibition in Düsseldorf, which included 45 of her later works. In 1968, over seventy of her drawings were displayed in a group exhibition. Sandmann avidly followed the 1970s women’s movement in Germany, and she supported the women’s art gallery Andere Zeichen (“Different Signs”) in West Berlin. In November 1974, at 81 years old, she helped found Group L74, the first postwar organization for elderly lesbians in Berlin. Sandmann also worked on the magazine published by the group, UKZ (Unsere Kleine Zeitung, “Our Little Newspaper”). For years, her drawing Lovers graced the cover page of UKZ.

Having overcome my lifelong resistance to visiting Berlin, I enjoyed the city and the Pride march and the nightlife that Berlin is famous for. I also learned the life story and saw the surviving works of a gifted lesbian artist. Gertrude Sandmann combined artistry with passion, humanity, and grit. Her Berlin is the one that I will always remember.

Emily L Quint Freeman is the author of the memoir Failure to Appear: Resistance, Identity and Loss (Blue Beacon Books).