“I PAINT PICTURES which don’t exist and which I would like to see” (“Je peins des tableaux qui n’existent pas et que je voudrais voir”). That is how Léonor Fini (1907–1996) summed up her artistic quest as a painter. She was one of the most wildly creative artists and iconoclasts of the mid-20th century. Diversely gifted, for the six decades of her career Fini realized her artistic potential not only in easel art forms but also in set design, book illustration, commercial art, and costume design for theater, opera, ballet, and cinema. She also wrote three novels, one of which, Rogomelec (1979), has been translated into English.

The artist was a friend and/or lover to some of the leading figures in literature and the arts, and was universally acknowledged for her beauty, intellect, imagination, and passion. During the peak of her fame in the 1930s, she was known as the “Queen of Paris,” attending balls and making headlines with her flamboyant attire. In many ways, she became the impresario of her own life, parts of which are akin to a piece of performance art.

Today, Léonor Fini is seldom written about or her paintings shown in gallery or museum exhibitions. It seems to me that Fini’s work is still rather indigestible for the establishment art world: too pansexual, too feminist, too out there. Also, her extensive œuvre reaches into so many genres as to defy classification, which is something that tends to vex both art critics and museum curators.

I had no idea who Léonor Fini was until one spring morning when I was exploring the 1st arrondissement in Paris on foot. This district of Hausmann-era boulevards and parks is the heart of the original city and what was once the seat of royal power in Paris, its most famous attraction being the Louvre Museum. Near the Jardin du Palais-Royal, I turned onto a diagonal street, Rue de la Vrillière. Nothing special, just a granite silo of walls with retail below and apartments above. I stopped for a moment outside the glass and wrought iron doors at no. 8 and peered inside, discovering a courtyard beyond, guarded by a stone sculpture on a plinth—a female sphinx, part crouching lion, part human, with full breasts and flowing hair. Above the exterior door, there was a commemorative plaque, the kind you see all over Paris, marking the residence or birthplace of a notable person. This one read as follows (I’ve translated into English):

Léonor Fini (30 August 1907–18 January 1996)

Painted and Lived in this House from 1961 to 1996

Well, anyone with a mythological woman on a stone platform outside her apartment must be worth finding out more about. So I headed to my favorite bookstore on the Left Bank, Shakespeare & Company, and asked the clerk to fill me in. She smiled slyly and answered in French: “Elle était formidable. Vraiment parisienne.” Another barrage of French ended with: “Elle aimait les chats” (“She loved cats”).

The Centre Pompidou, the most important Paris museum of modern art, directed me to books on Surrealism to learn more about Fini. What I’ve discovered in my research has confirmed my first impression that she was truly extraordinary. All of the dots began to connect: the female sphinx outside her front door, and her fondness for felines, and the art that she produced.

§

Born in Argentina, Léonor Fini was still a baby when her parents separated, at which point her mother took her back to her home in Trieste, Italy. Her father fought for custody and even tried to kidnap Léonor at one point, but her mother won out. As a studious teenager, Léonor read the writings of Freud and was particularly interested in the interpretation of dreams. She was extremely gifted as a painter but never received any formal academic training. At age seventeen, she was already getting commissions for portraits and shows. She decided to move to Milan, the center of the Italian art scene, and quickly fell in with the Novecento group of Surrealists, which included Giorgio de Chirico. Her work was featured in their group show in 1929.

In 1931, Fini decided to move to the ever dazzling and alluring city of Paris. Bright, temperamental, and utterly unique, she soon befriended quite a few of the best-known Surrealist artists: Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, Leonora Carrington, and René Magritte. She exhibited her work alongside these and other Surrealist artists in Paris, London, and New York, sharing their common interest in dreams, the unconscious, and psychic metamorphosis.

Fini herself never accepted the label of “female artist,” and likewise never considered herself a Surrealist. Above all, she refused to sacrifice her independence to the dictates of André Breton, the leader of the movement, who held misogynistic views that she abhorred. Nonetheless, her works have been part of major Surrealism exhibitions. In 1936, her work was included in the exhibition titled Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism at the Museum of Modern Art, while simultaneously it was on display in a show with Max Ernst.

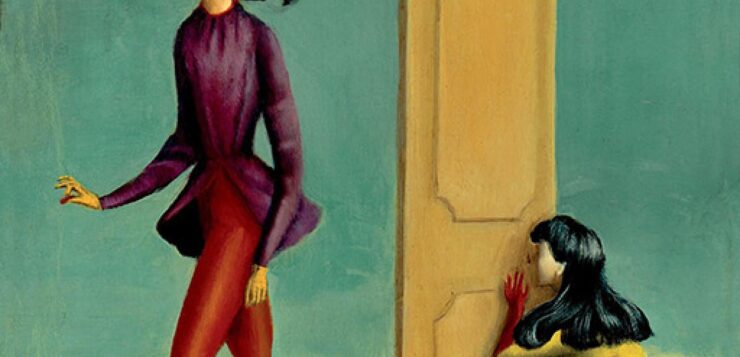

Merging various influences in her meticulous brush strokes, lavish palette, and vivid textures with her interest in psychoanalysis, philosophy, mythology, and sorcery, Fini’s subject matter is all about women, who appear in her work as strong, sexual creatures who dominate any canvas that they inhabit. Her paintings celebrated dreamlike environments, provocative relationships, human and animal transformation, ambiguity, and role reversal. Refreshingly for an artist, she depicted female sexuality from the perspective of a woman, not as an object of desire for a man.

Her most famous works include Self-portrait with a Scorpion (1938), Figures on the Terrace (1939), Alcove (1941), Woman Sitting on a Nude Man (1942), and Ideal Life (1950), along with numerous portraits—famously of Jean Genet—and especially self-portraits. Never a slave to convention, she also produced, in 1942, the first erotic male nude ever painted by a woman. One of the symbols she used, and inverted, in her art was that of the sphinx. Unlike those of the male Surrealists, hers is a female sphinx, who’s presented as erotic and omnipotent. In Sphinx Amoureux (1942), a male nude lies limp in the arms of a Fini-headed sphinx. She frequently portrayed men as passive and sometimes as androgynous figures.

As the artist gained a reputation, her subject matter included erotic scenes of lesbianism. Fini freely acknowledged her experience of same-sex love but refused to accept a lesbian identity, remarking: “I am a woman and have had the ‘feminine experience’ but I am not a lesbian.” Her explicit homoerotic paintings include Le Long du Chemin (1967) and L’Entre-Deux (1967). Both depict an erotic scene involving two women.

Then there are the Dalí-like surreal paintings with homoerotic images, notably Le leçon de botanique (1974), in which a nude female figure appears to be discoursing about female sexual anatomy, shown as a large close-up image in quasi-human, quasi-botanical form. The expression on that figure’s face seems ecstatic rather than scientific. The other figure is an armless female, nude from the waist down.

While mainly known for her paintings and engravings, Fini was also a talented designer, including the bottle design for the “Shocking” brand of perfume made by Schiaparelli. She also fashioned costumes for theatrical and operatic productions. Some of her set and costume work included George Balanchine’s ballet Le Palais de Cristal, Jean Genet’s play The Maids, and Federico Fellini’s film 8½. In the final phase of her artistic life, she devoted herself to writing and illustration, producing the artwork for the novels of many writers.

§

In addition to the Surrealist painters, Fini befriended or worked with numerous others in a wide range of artistic endeavors. Indeed, the list of people she knew, collaborated with, or influenced artistically over the ensuing decades reads like an inventory of the European avant-garde thinkers and creative geniuses of the mid-20th century: Jean Cocteau, Man Ray, Dora Maar, Anna Magnani, Albert Camus, Federico Fellini, Elsa Schiaparelli, and Jean Genet, to name but a few. She was also on good terms with American director John Huston, designing the costumes for his 1968 film A Walk with Love and Death.

Some of the most famous photographers of the time, notably Henri Cartier-Bresson, did not conceal their desire to immortalize Fini. A woman of great beauty, she enthusiastically served as their model in provocative and erotic poses without appearing shy or sexually insecure. In 1936, she posed in the nude for the famous gay New York fashion and celebrity photographer George Platt Lynes. Faithful to her desire to be a work of art in her own right, she appeared often in elaborate costumes, adorned with feathers, jewelry, and furs, taking on the appearance of a mythological goddess.

Fini was proudly polyamorous. She once said: “Marriage never appealed to me. I’ve never lived with one person. Since I was eighteen, I’ve always preferred to live in a sort of community. A big house with my atelier and cats and friends, one with a man who was rather a lover and another who was rather a friend.”

She also had many affairs with women, which continued during her long-term relationships with two men. While in her thirties, Fini entered into a scandalous ménage à trois with a Polish essayist, Konstanty Jeleński, and an Italian count, Stanislao Lepri. On the upside, Lepri abandoned his fascist diplomatic career in Italy as a result of her influence and became a painter instead.

And the cats? Fini and her two lovers stayed together in a Paris apartment that she remodeled and filled with her cats and artwork. She acquired 23 cats that would sometimes share her dining room table and sleep in her bed. Her beloved Persian cats appear frequently in her paintings. Cats seem to have been a kind of avatar of Fini herself.

In a pansexual paradise of her own invention, Léonor Fini is the impresario, the set designer, and the costume designer. Sagacious, fierce, and beautiful female deities would reign supreme. As her consort, Fini’s ideal man is a natural androgyne, morphing with the feminine. In such a place, Fini would surely welcome and celebrate all imaginable genders and consensual sexual and sensual possibilities.

Cover Art: Léonor Fini’s Figures on a Terrace, 1938.

Emily L. Quint Freeman is the author ofFailure to Appear: Resistance, Identity and Loss (2020), a memoir. A collection of her essays and creative nonfiction is in the works.