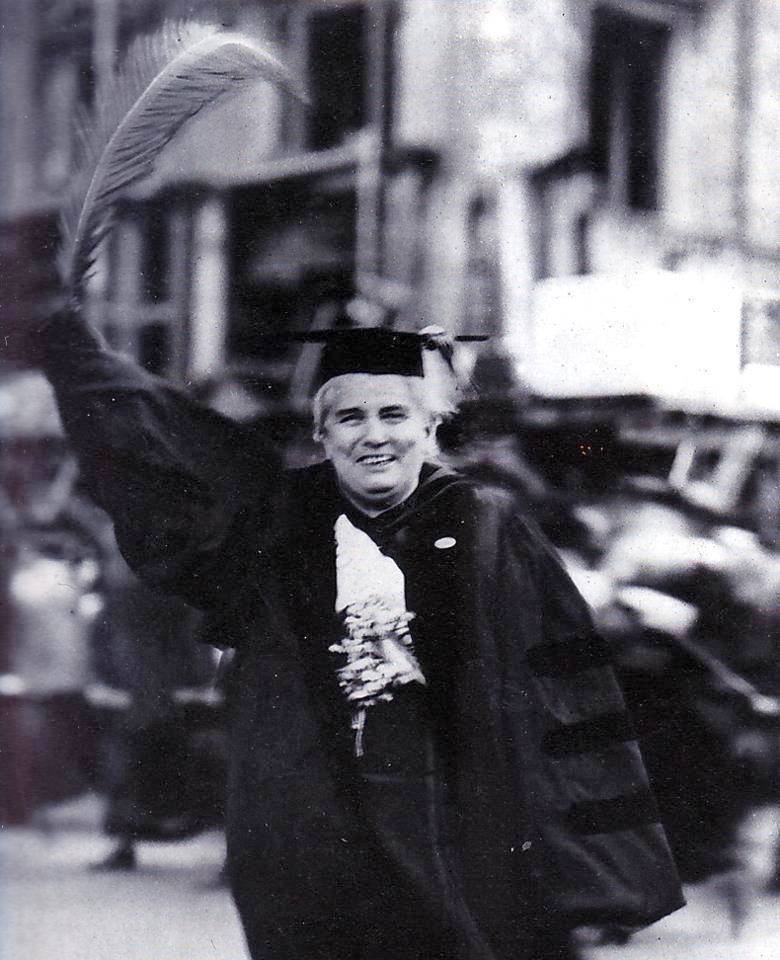

ANNA HOWARD SHAW (1847–1919) aptly titled her autobiography The Story of a Pioneer because she was the consummate trailblazer. A poor immigrant, a frontier settler, an ordained female minister, a self-made woman in an age of self-made men, a renowned feminist orator and voting rights activist, she was also a lesbian whose orientation was hidden in plain sight. In books, in classrooms, and in the media, Shaw is often presented as a bumbling or ineffective figure (when she’s considered at all). The truth is, she was one of the most revered progressive women of her time—a friend to presidents who played a pivotal leadership role in the epic struggle for women’s suffrage.

Shaw’s same-sex partnerships nurtured her through most of her adult life, especially during her later years as an activist. Living openly with other women but never declaring the nature of their relationship, Shaw’s status as a lesbian (our word, not hers) could only have strengthened her quest to empower women to have independent voices and to play an active role in politics.

In the 1880s, Shaw broadened her horizons, using her rhetorical brilliance, honed at the pulpit, to become a spokesperson for temperance and women’s suffrage. As a result of her increasing activist involvement and success as a public lecturer, she met the woman who would become “the torch that illumined my life”: legendary feminist Susan B. Anthony (1820–1906). Shaw’s warmth and humor, along with her staunchly feminist perspective, appealed to Anthony, who immediately sensed the articulate younger woman’s potential for reaching a wide audience. Shaw’s sermon “The Heavenly Vision”—a rapturously inclusive meditation on diversity—resonated with Anthony and made Rev. Shaw a rising star for “the Cause.”

There’s an astonishing scene in the memoir when Anthony visits Shaw’s hotel room near the beginning of their relationship. They’re both attending a women’s conference, and at the end of the day’s events, Shaw gets into bed. Then Anthony waltzes into Shaw’s room and makes herself comfortable in a big easy chair, spreading a rug over her knees, while Shaw props herself up on pillows, taking in the illustrious feminist’s every word. The conversation lasted until coffee the next morning. “Hours passed and the dawn peered wanly through the windows, but still Miss Anthony talked of the Cause—always of the Cause—and of what we two must do for it … sweeping me with her in her flight toward our common goal, until I, who am not easily carried off my feet, experienced an almost dizzy sense of exhilaration.” During this extraordinary all-night bonding session, Shaw finally found the lesbian mother figure, mentor, and soulmate that she’d been searching for.

Susan B. Anthony, in turn, found a daughter-in-law. In fairly short order, Shaw became the life partner of Anthony’s lesbian niece, Lucy E. Anthony, a suffragist secretary who was Susan’s niece by blood but had become more like a daughter to her. The home of Susan and her unmarried sister Mary was always a home-away-from-home for Anna and Lucy. Thus this quartet of women created a fiercely devoted queer family that was as meaningful and emotionally supportive as any heteronormative family could be. (Anna, in her grueling travels throughout the U.S. and Europe, does seem to have had dalliances with other women but was always firmly committed to Lucy, her manager and de facto spouse.) Thousands of letters between Anna and both Lucy and Susan have been lost or destroyed, according to Shaw scholar Trisha Franzen—a huge loss to LGBT and feminist history.

Shaw spent the rest of her life expanding support for both state and national voting rights in her high-profile role as president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (1904–1915), and after that by coordinating women’s groups during World War I, for which she was the first woman to be awarded the Distinguished Service Medal. She also participated in the naacp’s National Conference on Lynching, but was taken ill while touring with former President Taft for the League to Enforce Peace.

Shaw died from pneumonia in 1919, about a year before the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified. It didn’t become the law of the land until August 26,1920, which means that the centennial of women’s right to vote is upon us. Perhaps her death just shy of ratification is one reason that Shaw doesn’t get enough credit for this Constitutional milestone. Alas, Shaw is usually overshadowed by her lionized suffragist sisters Carrie Chapman Catt, an adept political strategist, and Alice Paul, a militantly radical activist and hunger striker. But if others were better at organizing campaigns and publicizing protests, Shaw was undoubtedly the movement’s most popular public speaker and its folksy heart. Her brand of soft-power diplomacy with politicians was a factor in the suffragist movement that isn’t sufficiently acknowledged.

Lucy Anthony was with Shaw when the latter died in their Moylan, Pennsylvania, residence, which Shaw had painstakingly built as their private refuge. While Lucy was mourning the death of her “precious love” of three decades, Shaw was being proclaimed the “Mother of Suffrage” in an obituary. With her resounding voice, fabled stage presence, and tireless work ethic that helped bring the nation to the brink of suffrage for all citizens, Shaw had fulfilled the dying wishes of her surrogate mother, Susan B. Anthony.

Sted Mays, who lives in Atlanta, is the author of recent pieces on Susan B. Anthony that appeared in this magazine (March-April 2020) and in LgbtqNation.com.