“THERE WAS ONCE a young invalid. Whose lungs would do nothing but bleed.” Aubrey Beardsley wrote these words in 1896 as a young artist while stuck indoors in filthy weather “to amuse myself,” in his words, while lamenting the state of his health. At age 23 he had just two more years to live.

In 1891, Beardsley described himself as having a “sallow face, sunken eyes, red hair and shuffling gait.” As such, he was a walking stereotype of the “doomed youth” who populated the British Decadent movement: a worshipper of ethereal beauty and “Art for Art’s sake.” He burst onto the artistic scene in the 1890’s with breathless energy—quite literally, alas, as he suffered from tuberculosis—and was obsessed with that most dangerous of topics in late Victorian England: sex.

Beardsley’s art is eerie, graphic, and erotic. He draws us into beautiful worlds of spectacle and decadence, but always at its center is sexuality in some guise. Elements of the sensual and the crude in his work are inescapable. He even wrote a novel titled Under the Hill that can only be described as pornographic, in which, among other things, Venus masturbates a unicorn.

Beardsley was born into a lower-middle-class family in Brighton in 1872 and was diagnosed with tuberculosis as a child. Consequently, he would have known from an early age that his days were numbered. He left school at sixteen to work as an insurance clerk at the breweries, where he stayed until he was “discovered” by Robert Ross, Oscar Wilde’s lover. This meeting led to his being introduced to the largely homosexual circle of Æsthetes that surrounded Wilde, men who lived extravagantly, experimented dangerously, and challenged the norms of Victorian society.

A certain amount of academic ink has been spilled on the question of whether Beardsley ever experienced sex outside of his art. He tended to spend his time with society’s most notoriously gay men: Robert Ross, Oscar Wilde, William Rothenstein, and Max Beerbohn, to name but a few. Yet most historians, such as Matthew Sturgis and Stephen Calloway, both biographers of Beardsley, argue that he was basically heterosexual, citing as evidence the youthful poems he sent to one Miss Fenton, and his admiration for the ladies of Brighton theatrical society. Yeats also remembered him saying: “Yes, yes I look like a sodomite … but no I am not that.”

However, accusations of homosexuality, which was then a criminal offense, plagued him throughout his life. In 1925, he was also accused by Frank Harris, a prominent journalist of the 1920s, of having had an incestuous relationship with his sister Mabel, who supposedly miscarried his child (Sturgis, 1998). Yet despite these rumors, there is a frustrating lack of evidence that Beardsley ever actually had sex with anyone at all.

But perhaps we’re looking at the question of Beardsley’s sexuality from the wrong perspective. In the 1890s, sexuality itself was undergoing a rapid change as it was being discussed and studied and redefined by psychologists such as Sigmund Freud, who horrified British society by dragging sex into the limelight. The term “homosexual” itself had been coined earlier but was not in general use. And while there flourished what we would call a gay subculture, few men, even those in Wilde’s circle, would have described themselves as homosexuals in our sense of the term. Beardsley lived for just 25 years, and most of his correspondence was destroyed, so his art is essentially the only place we have to look for any insight into his mind and motivation.

His first art commission, in 1893, was to illustrate Mallory’s Morte d’Arthur, and it came from the publishers J.M. Dent and Company. Even at this early stage, his work is full of sexual innuendo. In his picture How Arthur Saw the Questing Beast, King Arthur is portrayed as a louche figure half lying in repose. Wrapped in silk, the stylized armor that encases his legs is flimsy and decorative. This Arthur is no warrior but a delicate, almost feminine figure with long black curls, watching a faun leap about in the forest as snakes slither sinuously in the black pool below, tongues extended suggestively. For Beardsley and other artists of the time, the forest represented a symbol-studded landscape in which there were numerous obstacles to challenge one’s virtue and even one’s sanity. The languid sexuality in the picture is inescapable, and what makes it even more interesting is that the figure of Arthur may have been a self-portrait. In any case, there is little doubt about its challenge to traditional standards of masculinity. The slender “dandy” figure could have been taken from any of Wilde’s texts.

Later in the series, Beardsley drew his knights as pale and sickly figures who use swords as walking sticks and gaze into flowers and phallic floral arrangements. The obsession and inclusion of the phallic was not new in art, but the open interest of a feminized male figure toward the phallus was. These knights gaze upon them as if searching to understand the mystery of their beauty. And while this is not necessarily an argument for Beardsley’s homosexuality, this fascination with the phallus is something that needs to be acknowledged and explained.

The notion of sin makes an appearance in these images as something “fascinating, provocative and irresistible,” in Muriel Whitaker’s words (1975). It’s a theme that continues into his later work. Some of Beardsley’s most famous drawings are the sixteen commissioned by Wilde to illustrate his risqué tragedy Salomé. The image that’s most closely associated with Salomé today is titled The Climax. The drawing shows Salomé having just kissed the severed head of John the Baptist. Orientalism, Symbolism, eroticism, and autoeroticism are all present in this one image. Salomé had persuaded her stepfather Herod to cut off John the Baptist’s head. In return, she satisfies his lust for her by performing an erotic dance. Herod receives his reward, and Salomé receives hers. It is with a look of almost orgasmic joy that she stares intently into John’s face as blood pours onto the ground, where it feeds a phallic-looking lily.

In earlier versions of this work, deemed to be risqué even by the Decadents, Salomé, along with other male youths, is masturbating. Death, sex, fetishism, and erotica combine in this image to demonstrate that sexual satisfaction can begin and end in the mind, requiring no physical act—a new and dangerous idea for Victorian England, where sex was for procreation, not for pleasure, much less pleasure of the self-induced kind. Combining these various elements also allowed Beardsley to flirt with the boundaries of Victorian censorship. The reaction even to this sanitized version, however, was one of horror. Kenneth Clark, writing in 1976, states that it aroused in a single image “more horror and indignation than any other graphic work hitherto produced in England.” In all versions, Salomé is shown as powerful and in charge of her own sexual desire, which was enough to horrify patriarchal England.

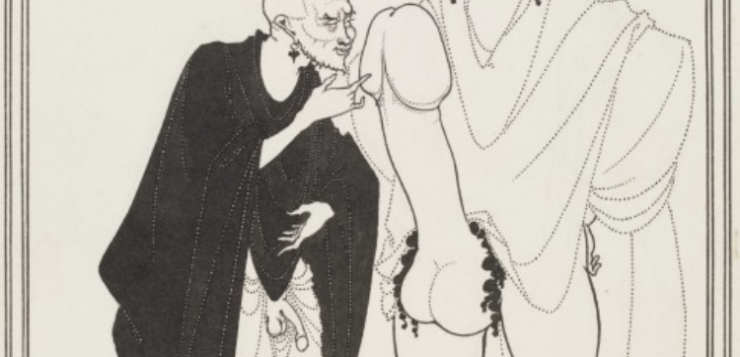

The Peacock Skirt, from the same series, again depicts Salomé, this time wrapped in a long, flowing robe, decorated with peacock feathers. Once again she is shown as strong and masterful, conquering the young man, who stares back in awe. The man is again presented as effeminate, thin, and garbed much like Salomé, in a long robe. Indeed it’s hard to determine his gender without close examination, yet his attraction to Salomé is obvious. In this image, Beardsley challenges the traditional depiction of a woman. Salomé is self-possessed and sexually charged, and she dominates the scene—a bold depiction of feminine sexual desire opened wide for all the world to see. Oscar Wilde called Beardsley “the only artist who could understand [the sexuality]of Salomé’s dance.”

In a career breakthrough, Beardsley became the arts editor of The Yellow Book, an artistic quarterly published from 1894 to 1897, and he used it to further explore art and its themes of sexuality right on the edge of moral decency. Dozens of his sinuous, black-and-white drawings filled the pages, appalling and fascinating in equal measure. Drawings such as The Toilet of Lampito, in which Eros powders the buttocks of a voluptuous woman, naked except for her lacy stockings, address sex in a much more earthy way than was customary: Eros is sporting an erection. Such images are sexual fantasies that explore and delineate the idea of sexual possibility and orientation.

Sturgis argues that Beardsley’s fascination with sex stemmed from his “obsession with surface. Without committing himself sexually he learnt the language and studied the pose.” Indeed, these drawings do seem to indicate that Beardsley intended to shock, even though he was safely detached from the reality of sexual experience. Likewise he wrote in a letter to his publisher that he planned to “dress as a woman to take tea,” but there’s no evidence that he actually did so.

Beardsley always denied allegations of homosexuality, but when Wilde was arrested and charged with sodomy, he was said to be carrying a copy of The Yellow Book. Beardsley found his work under increasing scrutiny as people looked for evidence of homosexuality. Indeed many people thought they found it in his drawings, such as The Examination of the Herald, in which an older man with drooping genitalia examines a man with an impossibly large erect phallus.

After Wilde’s arrest, Beardsley was promptly sacked from The Yellow Book, which was unable or unwilling to protect him from allegations of “gross indecency.” Beardsley went on to take rooms at 10-11 St. James’ Place, an address described by the prosecutor at the Old Bailey as “a place of homosexual assignation.” He had now, by design, made his sexuality a matter of public speculation. Then, almost overnight, Beardsley’s promising career was essentially over.

None of this dissuaded Beardsley from his chosen course, and in 1896 he embarked on some of his most explicit drawings: the ones for Lysistrata and Juvenal’s Sixth Satire. Aristophanes’ Lysistrata famously features the women of Athens and Sparta ending a war by refusing to have sex with their men until they agree to make peace. Juvenal’s work satirizes the sexual activities, and the bodies, of women in ancient Rome. These pictures, such as Juvenal Scourging Women (1896) and Bathyllus Posturing (1896), were considered so obscene at the time that they were unpublishable and available for collectors only. The women in these images fondle each other constantly, causing their men to have enormous erections. Lust and sex here are being depicted as triumphing orgasmically over war and its horrors. The women hold the power and the men are slaves to their own lust. The overriding impression from these images is that sex is the inescapable, driving force behind everything humans do.

Another fascinating facet of Beardsley’s life at this time was his growing collection of “depraved” art, fascinated as he always was by the erotic. He wrote to his sister from Paris in 1897 that “I have bought two such delicious dix-huitième engravings from the Goncourt sale: Toilette de bal, Retour de bal … dreadfully depraved things.” Today we might describe them more accurately as “sensual.” In part I think this collection became the means through which he understood his own sexuality and developed his work. He never saw himself as an erotic artist, though he clearly loved the explicitly anatomical and the grotesquely ornate. “I have one aim,” he wrote, “the grotesque. If I am not grotesque I am nothing.” More importantly, he was running out of time, and by now the practice of sex, if ever a possibility, was undoubtedly out of reach. The art he created and collected became the only link he had left to a sex life, and possibly to life itself.

Above all, Beardsley saw himself as a great artist who could through his art champion the principles of æstheticism to which he was dedicated. He put sexuality at the center of the modern art movement, shocking polite society, and he explored the underlying storm and stress of sexuality long before it was taken up by the Surrealists. The world he created was one of sensuality, attraction, beauty, and power—all things that he was denied by a disease that killed one slowly at first before racing to a merciless end.

References

Clark, Kenneth. “Beardsley.” The New York Review of Books, Vol. XXIII No. 20, 1976.

Calloway, Stephen. Aubrey Beardsley. Harry N. Abrams, 1998.

Sturgis, Matthew. Aubrey Beardsley: A Biography. Harry N. Abrams, 1999.

Whitaker, Muriel A. “Flat Blasphemies: Beardsley’s Illustrations for Malory’s Morte Darthur.” Mosaic 8:2, 1975.

Rebecca Batley, a historian and writer, has a particular interest in the art of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Discussion1 Comment

I would refer anyone interested in Aubrey Beardsley to look at two books by Brigid Brophy: Beardsley and His World (pub. 1976) and Black & White: A Portrait of Aubrey Beardsley (pub. 1968). It is a sad state of affairs that Brigid Brophy has been ignored and largely forgotten over the years. It is worth remembering that during the 1960s and 70s she was one of the most prominant and forthright social campigners. Her absence from the history of the Gay and Lesbian Movement needs to be addressed – she was almost unique (as a married woman) to proclaim her bisexuality publicly, as well as her lesbian affairs.

D.R. Michael