IN PROSE both tender and assured, Irish-Canadian novelist Emma Donoghue delivers a historical novel that transforms a remote historical episode—a lesbian love affair between adolescents at a British boarding school in 1805—into a universal tale. Learned by Heart explores the evolving psyches of its two main characters as they go against the grain of social convention over the course of one school year, during which their lives undergo dramatic change.

Donoghue’s creation is the real-life love story of Anne Lister and the well-to-do Eliza Raine. Lister (1791–1840), who has been called “the first modern lesbian,” is the basis for the bbc/hbo drama Gentleman Jack. Raine was born in India to a British doctor and an unnamed Indian woman. Eliza and her sister came to England and were taken in by a white British family. While little is known about Eliza, much has been learned about Lister in recent decades after scholars discovered and decoded her five million-word diaries, parts of which have been published.

The school’s strictness makes even a slight departure from rules seem like open rebellion,

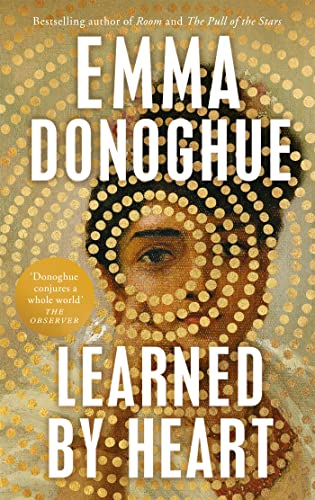

Cover photo for Learned by Heart.

something that Lister embraces with gender-neutral gusto, impressing the impressionable Eliza with her willfulness and intelligence. The more conventional Eliza quickly devotes herself to this remarkable girl. Doing so is risky in an era when women’s education was viewed mainly as a way to promote ladylike behavior and marriage suitability. Same-sex attraction between two girls was one of those loves that dared not speak its name. Nevertheless, the girls grow ever closer, delighting in each other’s company. Eliza’s “own existence at the Manor has been transformed by a wave of Lister’s wand.” They give themselves a mock marriage in the school chapel that seems torn from Shakespeare.

Donoghue—who wrote the bestseller Room (2010) and the screenplay for the 2015 film—is superb at capturing the unmediated feelings of love-soaked adolescents in their raw, vulnerable, disorienting, and excitable newness. Back in their icy dorm one night after seeing As You Like It and too excited to sleep, they enter the more-than-roommates phase. Donoghue handles the scene with both sublime sensitivity and stirring eroticism. The girls, wise beyond their years, are aware that others will not look kindly upon their romance. “What can it mean,” asks the narrator, “for the two of them to be in love? Nothing that needs explaining to them; nothing they could explain to anyone else.”

Interspersed letters from Eliza to Lister ten years after they left the Manor School show that the girls’ closeness did not last, a situation that played a role in steering Eliza into life-altering circumstances. A final letter from Eliza to Lister is painfully sad until we realize, with a sense of relief, that Eliza’s intelligence has allowed her to gain insight through heartbreak. She will survive, we fervently hope.

Claude Peck is a former Star Tribune (Minneapolis) columnist and editor. He edited Doug Argue: Letters to the Future.