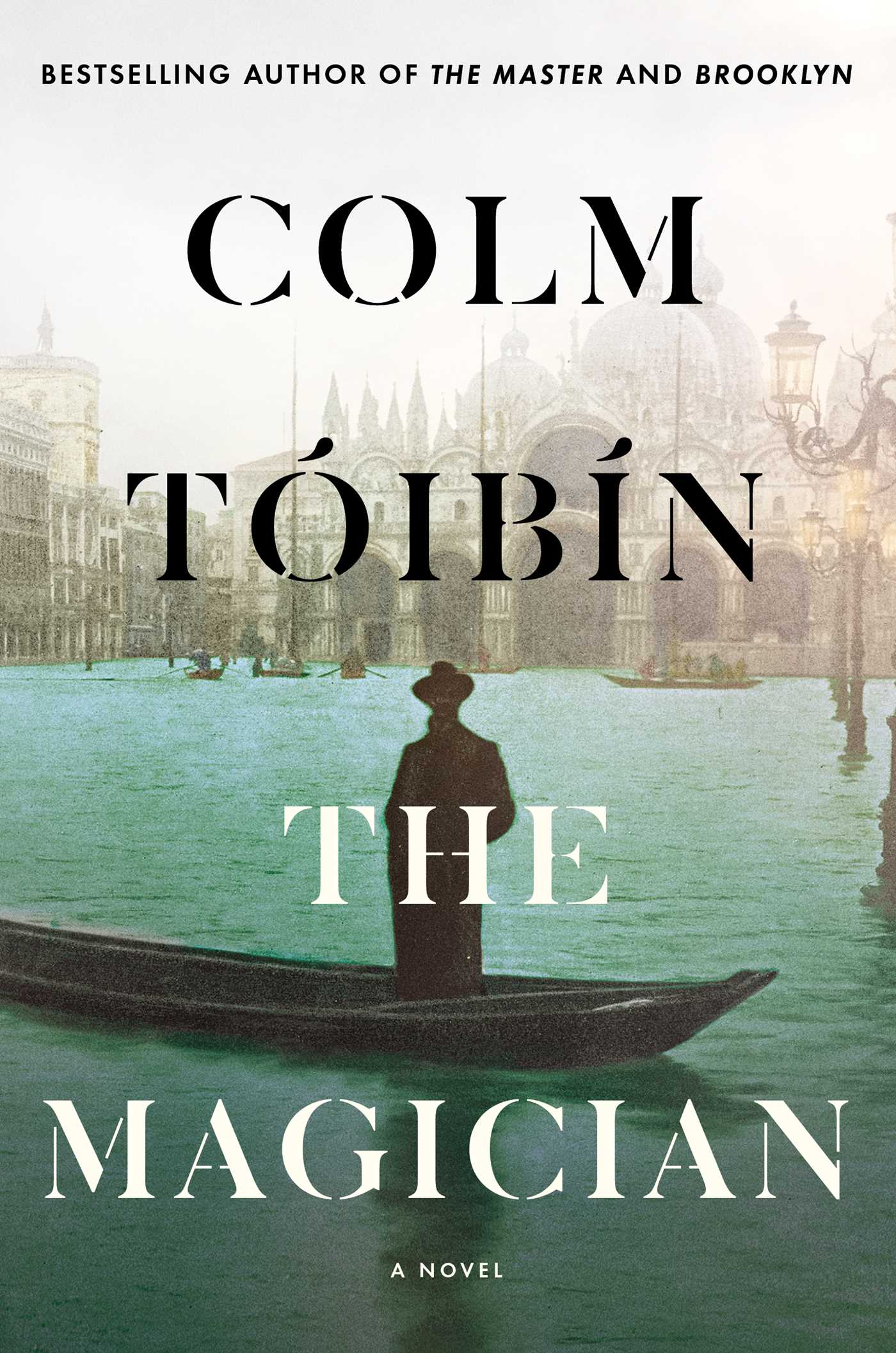

IN THOMAS MANN’S NOVELLA Death in Venice, a rhetorical question arises about the strange behavior of aging German writer Gustav von Aschenbach, who becomes obsessed with a beautiful, fourteen-year-old Polish boy at a resort hotel. “Who can unravel the essence, the stamp of the artistic temperament?” Mann asks. “Who can grasp the deep, instinctual fusion of discipline and dissipation on which it rests?” The short answer is that Colm Tóibín can, and he’s done it with great insight and sensitivity in The Magician, his novelized life of Mann.

In 2004, Tóibín published The Master, a novel that focused on a few key years in the life of writer Henry James. In contrast, The Magician paints a sweeping, cradle-to-grave portrait of the Nobel Prize-winning Thomas Mann, whose best-known novels include Buddenbrooks (1901), Death in Venice (1912), and The Magic Mountain (1924). But despite this difference in the scope of Tóibín’s two novels, similarities emerge between the lives and careers of his two literary subjects. James and Mann were both part of large, celebrated families that included other accomplished writers. Each felt strong same-sex attractions that were mostly unconsummated, and both became world famous in their lifetimes for their fiction. Mann, like James, was most comfortable in the seclusion of his study. And a final commonality: both Mann and James have found in Tóibín a worthy interpreter of their creative processes.

The Writer as Public Figure

It may be hard for American readers in 2021 to understand how big a deal Thomas Mann was in his own day. He courted approbation and it came to him early, along with material wealth. He was only 27 when he achieved fame for his first novel Buddenbrooks, about the decline of a prosperous German family. By 1949, a U.S. government agent could tell Mann that “after Einstein, you are the most important German alive.”

The Magician traces the historical arc of a European man of letters who bridged two centuries (Mann lived from 1875 to 1955), lived through two World Wars, and was always being judged by people of all political stripes as he walked a circumspect line from German nationalism during World War I to a somewhat tardy denunciation of Nazism during World War II. He would later settle in the U.S., where he was on cordial terms with Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. However, Mann was criticized as ungrateful to his adoptive country when he traveled to East Germany four years after the war.

Mann grew up in solemn, mercantile Lübeck, Germany, “where people lived as if winter were always approaching.” His father was a prominent businessman and a senator. His mother Julia was from Brazil, and she was artistically inclined. The senator died when Thomas was a teenager. He and his four siblings had been more-or-less written out of his father’s will, and the family business, which Thomas had been expected to inherit and run, was ordered to be sold. This prompted Julia to move to the more bohemian city of Munich, leaving Thomas behind to finish high school in Lübeck.

While there, in Tóibín’s reconstruction, “when Thomas wrote a poem about wanting to rest his head on his lover’s breast … the figure he imagined, the object of his desire, was Armin Martens,” a blond classmate. Like most of his crushes, it was unrequited. Mann’s same-sex attractions continued, flowering while in his twenties in a relationship with art and music student Paul Ehrenberg, described by Mann in his posthumously published diaries as the “central experience of my heart.” It’s a curious statement from someone who ended up having six children with his wife of fifty years.

Married with Children

Mann married Katia Pringsheim, from a wealthy Munich family of assimilated Jews, in 1905. She emerges as a fascinating figure in The Magician—resolute where Mann is indecisive, practical when he’s dreamy, supportive and protective of her husband but also independent, always aware of her husband’s attraction to young men.

A person of deep convictions, Katia goes ballistic at a high-powered dinner party in Washington, D.C., in 1942, asserting that nothing should be done to help rebuild Germany in the wake of an Allied victory. “It is not simply that there is a group of barbarians at the top,” she says. “The whole country, and Austria too, is barbarous. And the barbarity is not new. The anti-Semitism is not new. It is part of Germany.”

By this time Thomas Mann had joined his older brother Heinrich as an anti-fascist activist. In 1941 he launched a seventeen-city tour of the U.S. in which he extolled freedom and democracy and decried “the ruthless dictatorship” in Germany that had banned his books and forced his entire family into exile. In a series of recorded messages beamed into Germany during the war, Mann condemned the Nazi regime and sought to reassure Germans who opposed Hitler.

Family life—in Germany, Switzerland, France, and the U.S.—occupies much of Tóibín’s novel, and with good reason. Bourgeois and buttoned-down on the surface, the Mann clan was rife with turmoil—boundless creativity mixed with competition, suicide, national politics, exile, and famous friends (including the hilarious Alma Mahler, two husbands post-Gustav). Besides providing Tóibín with a steady stream of dramatic incidents to write about, the extended family weaves in and out of Mann’s fiction and gets involved in the affairs of Europe and America through the turbulent, war-torn decades of the first half of the 20th century.

Erika, Thomas and Katia’s oldest child, is depicted as strong-willed and outspoken. Radical, mostly lesbian, sharp-tongued, and funny, Erika secured a British passport by marrying gay poet W. H. Auden. She remained close to her parents, even living with them in the spacious house they built in Los Angeles; she was working as Thomas’ secretary when he was in his seventies.

The next oldest of the Mann children, Klaus, became a well-known writer in his own right as well as an anti-fascist crusader. Klaus was openly gay at a time when Germany had recriminalized homosexuality. Though emotionally distant, Thomas Mann often supported Klaus and his other adult children financially. He was devastated when Klaus died of a drug overdose in 1949; Klaus had been using morphine and other drugs for years.

Entertaining Evil

Whatever calamities befell the Manns, whatever shortcomings Thomas Mann had as a father and husband, his daily writing habit never varied. Some excellent episodes in The Magician endeavor to plumb the hard-to-explain process of formulating and writing a work of fiction, from Mann’s relatively early novella Death in Venice to his late novel Doctor Faustus (1947).

Mann was 66 when he and Katia moved into the sunny modern house they had built in Pacific Palisades. One evening, at his request, his musician son Michael brought his ensemble to the house to play Beethoven’s monumental late-career String Quartet No. 15 (Opus 132). In the novel, the music by the immortal German-born composer evokes for Thomas “the old world from which they have been forced to flee.” In Tóibín’s imagining, it also sparks grave self-doubt. Thomas “had made the great compromise. As he sat, perfectly washed and shaved, in his grand house, in his suit and tie, his family all around, his books all arranged on the shelves in his study with the same respect for order as his thoughts and his response to life, he could have been a businessman.”

With his homeland riven by war and barbarism, Thomas Mann resolves to move away from the “dry humor and social settings” of his earlier novels and summon the courage “to entertain evil in a book.” His version of Germany’s national legend in Doctor Faustus is about a modern composer who forms a pact with the devil after deliberately contracting syphilis, which he believed would bring both madness and musical greatness. That Mann made his composer homosexual and gave him syphilis did not endear the author to fellow German émigré Arnold Schoenberg, on whom the character was based. This section of The Magician, with its intersecting themes, biographical insight, and keen observations on music and literature, shows Tóibín at the peak of his literary power.

Having written about Henry James, Tóibín knows a thing or two about famous writers who were repressed homosexuals. Mann was unafraid to explicitly recount his furtive gay encounters in his journals. Writes Tóibín: “Not to have registered in his diary the message sent by the secret energy in a gaze would have been unthinkable. He wanted that which had been so fleeting to become solid.” Though he destroyed some diaries, others survived, went undiscovered by the Nazis, and began to be published in the 1970s, giving rise to new studies of Mann and his work. What’s interesting in Mann’s case is how freely he included gay and bisexual characters even in his published books—perhaps because of Germany’s relative openness to sexual variation when he was younger—and that he did so without creating much backlash.

Mann’s “dreams about sex had made their way into stories and novels, but in fiction they could easily be interpreted as literary games,” Tóibín writes. “Since he was the father of six children, no one had ever openly accused him of private perversions. If published, however, the diaries would make clear who he was and what he dreamed about. They would show that his distant, bookish tone, his personal stiffness, his interest in being honored and attended to, were masks designed to disguise base sexual desires.” Even a masked Mann, as Tóibín so brilliantly shows in The Magician, managed to write himself into the heart of 20th-century life and letters.

Claude Peck, editor of Doug Argue: Letters to the Future (2020) and a member of the National Book Critics Association, is based in Minneapolis, MN.