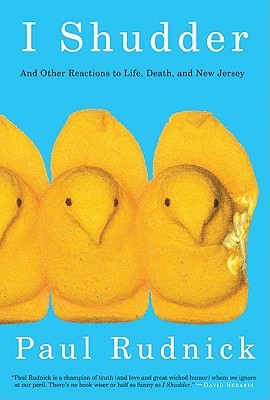

I Shudder: And Other Reactions to Life,

I Shudder: And Other Reactions to Life,

Death, and New Jersey

by Paul Rudnick

HarperCollins. 318 pages, $23.99

YEARS AGO, I was a subscriber to Premiere, a magazine that covered the film industry with glossy pictures of behind-the-scenes productions soon to be released and interviews with the stars. There was a regular column called “If You Ask Me,” written by Libby Gelman-Waxner, who presented herself as a Jewish soccer mom married to a dentist who had a son of bar mitzvah age. Libby had all sorts of opinions about the movies and the stars, and riffed on both with a zany mixture of Borscht Belt shtick and urbane wit. Innocent as I was, I read her as if she was, indeed, who she said she was, only to find out—through the gay grapevine, natch—that Ms. Gelman-Waxner was in fact the playwright Paul Rudnick.

Since then, Rudnick has gone on to greater fame, having had successful Broadway shows and written screenplays for Addams Family Values and In & Out. Libby’s gone, but Rudnick continues to sharpen his pen as a comic essayist and gay writer with the timing of a Catskills comedian and the sophistication of a well-connected New Yorker. The current collection, I Shudder, And Other Reactions to Life, Death, and New Jersey, finds Rudnick reviewing his life as a mild-mannered Jersey boy getting his first tiny studio apartment in Greenwich Village under the critical gaze of two aunts and a mother, who dish lines like Bette Midler doing Sophie Tucker. He becomes an assistant to the German émigré literary agent Helen Merrill, whose inability to pronounce the letter “r” makes her sound like Madeline Kahn doing Dietrich. He makes friends with such figure as the Hollywood producer Scott Rudin and Broadway costume designer William Ivey Long, a Southerner. In his portraits he reveals their particular eccentricities in a way that in a less deft hand would probably cost him their friendship. Rudnick is at his best when writing such character portraits, when his own contribution to the drama recedes and his players take center stage. However, the narrator’s voice is always unmistakably that of the wiseacre playwright sending up the foibles and manners of his subjects. The Scott Rudin piece is titled “Enter Trembling,” which gives us some idea of the fear and loathing the wunderkind gay producer inspired in those who didn’t know him. From the start, Rudnick declares that he himself is “often drawn to large-scale personalities, to people who refuse to behave themselves,” which might be his way of suggesting he has masochistic tendencies and likes being bullied. If so, Rudin is the man, describing his producer’s job as making “people do what they don’t want to do.” Rudnick illustrates this method when he’s told to produce a more comic rewrite of The First Wives Club. Turning the “WASPy matron” with a “retarded daughter” into one with a lesbian daughter instead, Rudnick then needs to justify why the three middle-aged women, played by Diane Keaton, Goldie Hawn, and Bette Midler, wind up going to a lesbian bar. Rudin tells him “Diane needs to talk to her daughter. … Write the scene.” Rudnick questions his producer with the logic of her sudden appearance there. Doesn’t she have a cell phone? “She left her phone at home,” Rudin continues. “Write the scene.” Rudnick persists: how does Diane know which lesbian bar will be the one where her daughter hangs out? And why would Diane bring along her two best friends? And why would Goldie and Bette’s characters agree to go with her? Rudin cuts the questions short: “Because they’re her friends, and because if you ask one more question I’m going to take you to a lesbian bar and ask all of the lesbians to kill you. Write the scene.” We suspect Rudnick has cleaned up Rudin’s language. All the same, Rudnick presents the producer as a mensch with a heart of gold, and the manners of a 1940’s Hollywood studio tyrant. Another tale in this collection is that of the alcoholic misbehavior of Nicole Williamson playing a John Barrymore send-up on Broadway in Rudnick’s play I Hate Hamlet (Rudnick’s essay is called “I Hit Hamlet”). Rudnick also details the making of the screenplay for In & Out, a satire about a middle-aged man, long engaged to be married, who’s suddenly “outed” by a former drama student winning an Oscar. Inspired by the actual incident of Tom Hanks’ first Oscar speech for the AIDS drama, Philadelphia, when the star indeed thanked an early mentor he identified as gay, Rudnick parlayed the idea into an unexpectedly successful cross-over hit. Part of the movie’s success was in its casting: Kevin Kline and Joan Cusack played the engaged couple, each rattled by the announcement of his homosexuality on national TV, while Tom Selleck, “taller and more absurdly handsome in person,” played a gay newscaster who awakens Kevin Kline to his sexual identity. Rudnick saves the best lines in this anecdote, however, for the perky Debbie Reynolds. After repeated takes of her tossing a bouquet to “a mob of eager female guests” in the wedding scene, Rudnick reports that the ever-lively 50’s star revived the bit players by shouting “All right, ladies! This time let’s really feel it! Let’s feel it in our vaginas!” Judging by the brevity with which Rudnick touches upon the more serious moments of his life—his involvement with act-up, the death of his father, and the cockroaches in that first apartment—it’s clear that he doesn’t do tragedy, surely a lapse in his Jewish genes. If you need a break from the current state of the union, I Shudder, as frothy as champagne, will lift your spirits without ever bursting your bubble.