Published in: September-October 2014 issue.

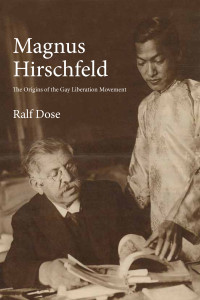

Magnus Hirschfeld: The Origins of the Gay Liberation Movement

Magnus Hirschfeld: The Origins of the Gay Liberation Movement

by Ralf Dose

Translated by Edward H. Willis

Monthly Review Press. 128 pages, $23.

THIS SHORT BIOGRAPHY of Magnus Hirschfeld—about 100 pages, minus the extensive bibliography and notes—first appeared in a German series of “Jewish Miniatures.” Its author, Ralf Dose, seems to assume a familiarity with the basic facts about its subject, and he organizes the life thematically instead of chronologically. This can be disorienting for readers who don’t come prepared with the necessary context. It’s worth persevering, because this is a good biography of someone who matters to us.