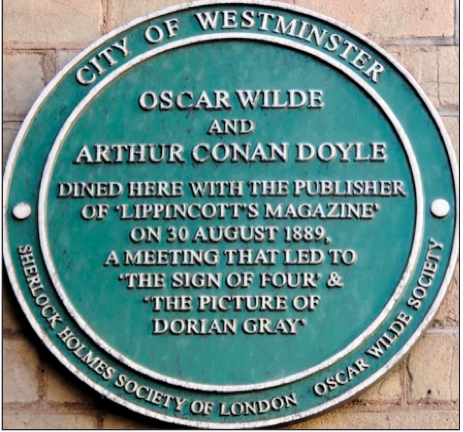

THE MOST consequential literary dinner of the English fin de siècle took place at the Langham Hotel in London in late August 1889, attended by Oscar Wilde and Arthur Conan Doyle and hosted by the editor of Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, Joseph Stoddart, who was in England to solicit contributions from British authors. The result was a commission from Stoddart to write two short novels: The Picture of Dorian Gray, which appeared in the February 1890 issue of Lippincott’s; and the second Sherlock Holmes novel, The Sign of Four (July 1890). The dinner was the first meeting of the two authors, and by all accounts each enjoyed the other’s company. Doyle called the occasion “a golden evening for me.”

At first glance, Wilde and Doyle seem the quintessential literary odd couple: the literary æsthete, trailing clouds of French décadence, and the stereotypical Victorian man: a hearty cricket-playing defender of the British Empire, opponent of women’s suffrage, and creator of the hyper-rationalist Sherlock Holmes. Other than sharing hansom cabs and impressionistic fog-shrouded streets dimly lit by gas lamps, the worlds of Dorian Gray and Sherlock Holmes could scarcely have been more different. And yet, the two writers’ works have more in common than one would suspect. Sherlock Holmes, especially in the early stories, exhibits many characteristics of the fin-de-siècle æsthete: addiction to cocaine (Dorian Gray develops an opium addiction) and an interest in the arts that includes playing the violin, attending concerts and the opera, and viewing an exhibition of Modern Belgian masters at a London art gallery. Doyle’s link to the age of The Yellow Book and the green carnation—which are associated with Wilde—are evident in the title of the first Holmes novella, A Study in Scarlet, which echoes the title of Wilde’s essay “Pen, Pencil, and Poison: A Study in Green,” featuring the artist and poisoner Thomas Griffiths Wainewright. These similarities have all been noticed before.

What has been overlooked is an early Doyle short story with an unmistakable queer subtext: “John Barrington Cowles.” Published three years before A Study in Scarlet, the story recounts the investigation into the suspicious death of the title character by his friend John Armitage, who is also the narrator. Armitage plays the role of a detective who finds he cannot satisfactorily explain his friend’s death, which comes about as a result of his liaison with a woman, Miss Northcott, who appears to have mesmeric powers, which she exploits to lead young men to their destruction (Cowles is not her only victim). The story, then, has a strong Gothic element and Armitage wavers between a supernatural and a natural explanation of his friend’s death: “It might seem rash of me to say that I ascribe the death of my poor friend … to any preternatural agency. I am aware that in the present state of public feeling a chain of evidence would require to be strong indeed before the possibility of such a conclusion could be admitted. I shall therefore merely state the circumstances which led up to this sad event as concisely and as plainly as I can, and leave every reader to draw his own deductions. Perhaps there may be someone who can throw light upon what is dark to me.”

The death of Cowles is not the only mystery in the story. There is another mystery, strongly hinted at but never explicitly stated, concerning the relationship between Armitage and Cowles. “John Barrington Cowles” can be read as a story about a repressed gay man in late-Victorian London who is unaware of his sexuality. What is “dark” to Armitage is his sexual attraction to Cowles. A suggestion of (suppressed) homoeroticism pervades the story, but it is an attraction of which Armitage is only dimly aware, if at all. Thus he is an unreliable narrator, not in the sense that he misleads the reader but that he lacks self-knowledge. However, to gay readers, both in the 1880s and today, his description of his relationship with Cowles hints unmistakably at strong sexual undercurrents: “[Cowles] came in time to concentrate all his affection upon me, and to confide in me in a manner which is rare among men. Even when a stronger and deeper passion came over him, it never infringed upon the old tenderness between us. Cowles was a tall, slim young fellow, with an olive, Velasquez-like face, and dark tender eyes. I have never seen a man who was more likely to excite a woman’s interest, or to captivate her imagination. His expression was, as a rule, dreamy, and even languid; but if in conversation a subject arose which interested him he would be all animation in a moment.” Cowles, who is coded as exotically (and hence erotically?) un-English, has certainly captivated Armitage’s imagination, and thus his interest in solving the mystery of his friend’s death may be motivated by more than intellectual curiosity.

Moreover, there is a doubleness in Cowles’ personality, a dreaminess and languidness that was typically a sign of sexual ambiguity in fin de siècle literature. This duality is paralleled by Cowles’ interest in both science and art. The narrator tells us that Cowles was “one of the foremost men of his year, taking the senior medal for anatomy, and the Neil Arnost prize for physics.” Yet we also learn that he was “passionately attached to art in every form, and a pleasing chord in music or a delicate effect upon canvas would give exquisite pleasure to his highly-strung nature.” (Both a passion for art and being “high strung” were also coded signals.) So it is hardly surprising that Cowles and Armitage first meet Miss Northcott, the story’s femme fatale, at the opening of the Royal Scottish Academy.

Northcott too is described as androgynous, blending masculine and feminine characteristics: “In my whole life I have never seen such a classically perfect countenance. It was the real Greek type—the forehead broad, very low, and as white as marble, with a cloudlet of delicate locks wreathing around it, the nose straight and clean cut, the lips inclined to thinness, the chin and lower jaw beautifully rounded off, and yet sufficiently developed to promise unusual strength of character. But those eyes—those wonderful eyes! If I could but give some faint idea of their varying moods, their steely hardiness, their feminine softness, their power of command, their penetrating intensity suddenly melting away into an expression of womanly weakness.” Miss Northcott is presented as a blend of male and female traits, and the particular description of her as a embodying a “Greek type” of beauty is based on the conventional fin-de-siècle image of Greek beauty as portrayed in classical and Renaissance statues of idealized bodies—especially male ones.

Thus it is possible to see the configuration of the three main characters in the story—Cowles, Miss Northcott, and the narrator—as a sexual triangle. Armitage’s hostility to Miss Northcott might then be interpreted as motivated, at least in part, by sexual jealously and by the suspicion that Cowles’ attraction to her is not a natural sexual attraction but the result of Miss Northcott’s supernatural powers. Significantly, at no point in the story does the narrator show any sexual interest in women, and Miss Northcott has no interest in him. Absent Northcott’s powers, would Cowles (or any of her other male victims) have succumbed naturally to her sexual attractions? The narrator certainly doesn’t. At first glance one might interpret Miss Northcott as a conventional femme fatal luring men like Cowles to a fatal sexual subordination, but her mesmeric powers are explicitly coded as masculine (her “steely hardness”), so what she seems to be exploiting is her male victims’ susceptibility to the sexual attractiveness of other men, which she uncannily detects—and then punishes. Miss Northcott’s power is thus an ability to exploit the secret weakness of her male victims and to impose her will on men who otherwise would not succumb to her. Miss Northcott can uncannily spot the love that dare not speak its name.

Nils Clausson, emeritus professor of English at the Univ. of Regina (Saskatchewan), is the author ofArthur Conan Doyle’s Art of Fiction: A Revaluation (2nd ed., 2019).