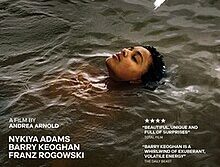

Capote

Directed by Bennett Miller

United Artists & Sony Pictures Classics

IN HIS 1965 “non-fiction novel” In Cold Blood, Truman Capote tried to see the world through a grain of sand. But he never considered whether the grain of sand in question—a 31-year-old loner who murdered four innocent people—might resent the writer’s efforts. On the whole, we’re no better: we scrutinize small-town killers, looking for sickness in ourselves; we devour famous writers, searching for our lives in their texts. In Capote, Philip Seymour Hoffman’s masterful portrayal of author Truman Capote vividly conveys the weight of those burdens as part of director Bennett Miller’s cautionary tale of the pleasures and dangers of storytelling.

Capote starts in the middle, on a night train in December 1959, with the author on his way to western Kansas to chronicle the murders of a small-town farm family. Not a subject one might immediately imagine for the 35-year-old gadfly of postwar literary New York, but who better to tackle the underbelly of America than the mid-century’s prophet of otherness? Capote’s fiction was populated by characters who were startlingly “queer”—which is to say, in the language of the 1950’s, not merely the gender-bending adolescents of Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948), but a congeries of ghosts, dwarves, funny uncles, and an eccentric New Yorker by the name of Holly Golightly. Nor was he alone. Joining Capote in this literary festival of Southern sexual dissidence were Tennessee Williams, Carson McCullers, and Truman’s own childhood friend, Harper Lee, played here with touching understatement by Catherine Keener.

At the heart of Capote stands the writer’s relationship with Perry Smith (Clifton Collins Jr.), one of the two Kansas killers, and the one who told the stories that became In Cold Blood. Capote forged a bond of vulnerability with Smith by sharing tales of his own difficult childhood—although the film erases Capote’s honest answer when Smith asked him in 1963 about his sexuality. (“Not that the answer isn’t obvious!” Capote would later quip to Smith in a letter.) But we watch Capote use Perry Smith for his own ends, turning his tragic life into a metaphor for the violence and disorder that roiled under the placid surface of the 1950’s. Hoffman’s Capote calls the killings a “goldmine” of a story and blurts, “when I think how good my book will be, I can hardly breathe.” It’s an accurate depiction. In a 1962 letter to Cecil Beaton, recently published in Gerald Clarke’s Too Brief a Treat: The Letters of Truman Capote (2004), Capote describes a visit to Smith in prison as “extraordinary and terrible,” then moves on, discussing plans for renting a summer villa in Corsica. As he lurched between seriousness and frivolity, Capote always wanted people to think he was trapped in the desperate predicament of the modern writer: “that part of me is always standing in a darkened hallway, mocking tragedy and death. That’s why I love champagne and stay at the Ritz,” he told an interviewer in the early 1980’s. But the film’s damning portrayal gets Capote more right than Capote did.

It’s not all damnation: Capote sympathetically conveys the burdens that the Kansas killings placed on their chronicler. In one scene, Capote reads an early draft of In Cold Blood to a rapt Manhattan audience; after the final sentence, the house explodes in cheers. As the camera pans across the audience, we share with Capote the sweet slaking of his thirst for adulation, but also see the hunger on the faces watching Truman—the suppressed longings for self-expression, many of them directed toward this queer prophet in an age of conformity. Capote once told an interviewer that “the great accomplishment of In Cold Blood is that I never appear once. There’s never an I in it at all.” But the I was in it all the more for never being spoken. The crowd was there that night to watch Capote live, not to hear whether Perry Smith and Dick Hickock might die. As the applause continues, the scene’s mood shifts from adoration to torment, and we understand why Truman Capote never completed another book in his remaining twenty years.

But we needn’t entirely mourn the fact that Capote never wrote another book: he continued to write shorter works—always his form of choice—and he devoted ever more energy to the cultivation of his life as a tragic work of art. If there was anguish in that, there was also champagne, and rooms at the Ritz, all paid for by the story of a cold-blooded drifter who left untouched his final meal of fried shrimp and garlic bread on the night that he was hanged.

Christopher Capozzola teaches American history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.