Published in: January-February 2006 issue.

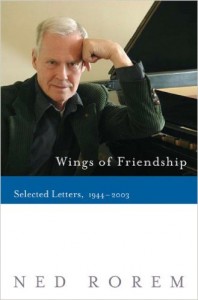

Wings of Friendship: Selected Letters, 1944-2003

Wings of Friendship: Selected Letters, 1944-2003

by Ned Rorem

Shoemaker & Hoard. 332 pages, $28.

LETTERS ARE both intimate and self-conscious. In them we describe our life as we would like at least one other person to know it. What kind of life does Ned Rorem describe in Wings of Friendship, a volume containing almost sixty years of his letters?

In part, it is the life of a gay celebrity. Rorem came of age in the years after World War II. He was a gifted composer, studying at Curtis and Juilliard and winning major prizes for his compositions before he was thirty.