Published in: November-December 2005 issue.

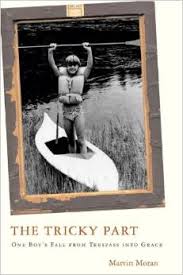

The Tricky Part: One Boy’s Fall from Trespass into Grace

The Tricky Part: One Boy’s Fall from Trespass into Grace

by Martin Moran

Beacon Press. 285 pages, $23.95

“A FRYING-PAN of shameful loves sizzled loudly all around me,” writes a brilliant, sensitive man in his early forties, remembering the uncontrollable lusts of earlier years, “and theatrical shows seized hold of me.” The writer is not Martin Moran but St. Augustine, recalling his student days in Carthage in the Confessions. Yet, although Moran’s life has taken a very different trajectory from that of the saint, his own memoir of “shameful loves” and “theatrical shows” burns with the same spiritual intensity as Augustine’s work.