“I don’t know if I will live to finish this. … I’ve watched too many sicken in a month and die by Christmas, so that a fatal sort of realism comforts me more than magic. All I know is this: The virus ticks in me.”

WITH these challenging words, which would soon become famous, Paul Monette began his 1988 work, Borrowed Time: An AIDS Memoir. In the same year he had published his poems, Love Alone: 18 Elegies for Rog. The two works together serve several purposes: they prove Monette’s love for Roger Horwitz, who died of AIDS in 1986; and they leave an indispensable record of the times. They prepare for Monette’s own death from AIDS in 1995.

Monette was born in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1945 and was educated in the east. His memoir, Becoming a Man: Half a Life Story, whose title anticipated that he would live only “half a life” before dying of AIDS, won the National Book Award for 1992. Younger writers such as Noel Alumit, Eric Gutierrez, Brian Leung, and Christopher Rice have noted the book’s huge influence on their work. It was reprinted in 2004 with a foreword by Kathryn Harrison. It was in Boston in 1974 that Monette met Horwitz, whom he termed “the greatest man I have ever known.” In 1977 they moved to Los Angeles, where Horwitz worked as a lawyer and Monette wrote teleplays, screenplays, and novelizations of movies, as well as less commercial works, including poems, novels, and nonfiction.

To mark the tenth anniversary of Monette’s death and what would have been his sixtieth birthday, the UCLA Library has mounted a major exhibit this fall from the Monette papers, titled “One Person’s Truth: The Life and Work of Paul Monette.” The quotation is from an interview Monette gave to his friend Malcolm Boyd, the gay writer and Episcopal priest: “One person’s truth, if told well, does not leave anybody out.” In 1993 Monette was the first to give his papers as an openly gay man to UCLA, and this gift has been supplemented with additions from his surviving lover, Winston Wilde.

The collection contains over 10,000 items, including manuscripts, publication materials, photographs, and audio- and videotapes. There are letters from notables both straight and gay in the literary and activist worlds: from Carol Muske Dukes and Judith Light, from Betty Berzon, Eloise Klein Healy, Richard Howard, J. D. McClatchy, Torie Osborn, Lev Raphael, and Terry Wolverton, among many. Particularly poignant are hundreds of fan letters, written even upon publication of his book of elegies, but particularly for Borrowed Time. They came from men and women who were caregivers or ill themselves, and who at the time saw nothing in literature that reflected their concerns. Letters after Becoming a Man often share the reader’s own coming out experiences, an invaluable compendium of gay life at that time.

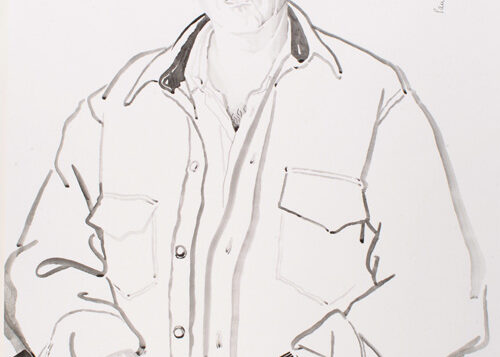

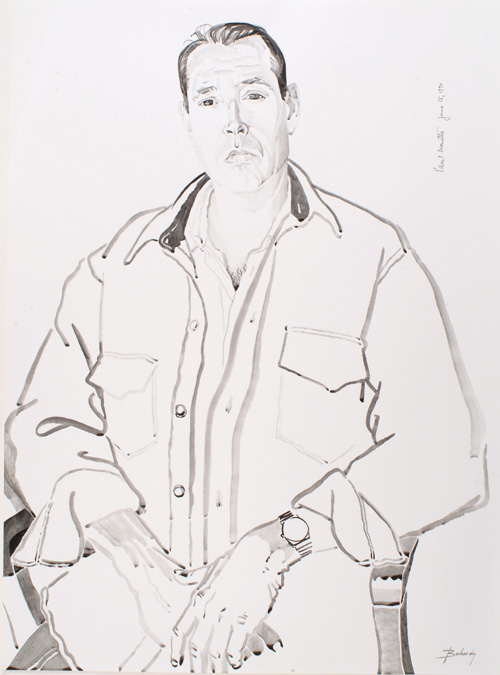

The exhibit’s 200-plus items reveal Monette striving to develop and communicate his feelings and ideas. The exhibit also features portraits donated by LA artist Don Bachardy and by photographers Tom Bianchi and Mark Thompson. The influence of Monette’s work was spread through musical compositions, too, such as those by Ned Rorem and Roger Bourland, which were premiered by gay men’s choruses in New York and LA. Monette considered himself a “child of Hollywood” and did all of his mature work in that city. Before the two AIDS works, he wrote poetry and then comic novels inspired by or set in LA. Critic David Román located these novels in the tradition of Shakespearean comedy, where plot complications are all resolved in the end. They are also in the tradition of Hollywood movies and especially its screwball comedy era of the 1930’s and 40’s.

He stopped writing poetry until after Horwitz’s death, at which point he began an entirely new style of confrontational poems. He would start writing them in his journals and later type them out and make additions in longhand. These manuscripts are a fascinating look into the creative process. The two novels written after the AIDS books were inspired by his new lover, Stephen Kolzak. Mixed with early manuscript leaves of what is perhaps his best novel, Afterlife (1990), about AIDS widowers in LA, is a draft of “Stephen at the FDA.” This celebrated later poem commemorates the anger and rage of protesters, including Kolzak, at the fact that the FDA was slow in releasing new and experimental drugs that might save their lives.

After Kolzak’s death, also from AIDS, Monette met Winston Wilde, and the works through the years with Wilde are among his best. He produced Becoming a Man without printed manuscripts, writing it with dispatch on a computer. He selected poems from his body of work for the collection West of Yesterday, East of Summer, and compiled his recent personal essays for Last Watch of the Night (both in 1994). He wrote more spiritually about his life in “My Priests,” which focused on his Buddhist, Catholic, and Episcopal friends.

Also on exhibit are the final notes for works he didn’t finish. He previewed a short fable, published posthumously as Sanctuary (1997), by reading from it himself at a GLAAD benefit in his honor. Monette characterized himself and Horwitz as “warriors together” in their struggle against AIDS. He returned to this image in his final fable with two female animals, a fox and a rabbit, whose same-sex love goes across species. At one point the two “embraced with the fervor of a couple of soldiers set to do battle the next day.”

Monette did not give up his battle until the end. He was an eloquent and handsome man, and while he didn’t want to be an AIDS poster boy, he passionately delivered his needed protest for the GLBT community in the early 1990’s, speaking in such disparate venues as The Geraldo Show, the Library of Congress, and St. Thomas Episcopal Church, Hollywood. He established the Monette-Horwitz trust to reward those making significant contributions toward eradicating homophobia. The Trust, which is administered by his brother Robert Monette and an advisory committee, has given 26 monetary awards since 1998 to both individuals and organizations.

Dan Luckenbill, who works in technical processing at UCLA’s Young Research Library, curated the exhibit under discussion. “One Man’s Truth: The Life and Work of Paul Monette” runs to Nov. 19 in Los Angeles. (Visit: www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/monette.htm.)