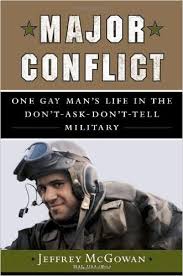

Major Conflict: One Gay Man’s Life in the Don’t-Ask-Don’t-Tell Military

Major Conflict: One Gay Man’s Life in the Don’t-Ask-Don’t-Tell Military

by Jeffrey McGowan, MAJ, USA (Ret.)

Broadway Books. 278 pages, $24.95

AT ONE TURNING POINT in this moving and romantic book, author Jeffrey McGowan, at the time a U.S. Army artillery lieutenant, hits bottom as he goes to war in Operation Desert Storm, knowing that he must hide the fact that he’s gay and in love with a fellow officer. He asks himself: “Why could I be a soldier, but not a man?” The story builds as McGowan tells us how he went from choosing to remain silent to deciding that he had to escape from the strictures imposed by the “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy when it was instituted in 1993.

Major McGowan frames his story compellingly by showing that, even after Stonewall in the 1970’s when he was growing up, there were few positive masculine role models for young men who perceived themselves as different. He didn’t feel feminine, and “being a man” was linked with aspiring to an occupation like the military. At the same time, he regarded “the role of soldier and homosexuality as mutually exclusive.”

McGowan joined the military to become a man, delaying his future conflict with being homosexual but finding himself amid possible objects of his desire. Steven Zeeland, who has authored studies and even erotica about men in several branches of the U.S. military, has determined that what excites gay men about the military is the opportunity for homosocial masculinity. In the Army, dozens if not hundreds of men often comingle in naked situations. McGowan doesn’t describe the physical abundance of these situations, but, more like a romance novelist, zeros in on “a glimpse of a soldier’s hairy legs; the clean-cut back of a neck; a strong, wide wrist banded with a watch.” McGowan does detail his consummated sexual encounters, often using military language, as when he “explodes” during an orgasm.

His main affair was with Paul, a fellow lieutenant whose “face gave the impression of a vague cruelty that was somehow pardoned, or perhaps enhanced, by his beauty and his youth.” He saw Paul before, during, and after Desert Storm, but only after the conflict did their affair become physical. The tension became unbearable when, coming out of a gay bar, Paul was seen by some men in his unit. He confronted McGowan to inform him that he wanted to remain in the military and to marry heterosexually. But he also wanted his physical relationship with McGowan, who, after this revelation, wished to end the affair. Things were even messier than that, in fact, and their story is a riveting one to follow.

The sexual explicitness and bombast of his fellow soldiers amused McGowan, and he found ways to participate and yet disguise the fact that he was gay. But the homophobic talk of his fellow officers was frightening and surprised even the veteran McGowan: “The sheer intensity of their animosity was truly astounding. Where did that come from?” Tension re-entered when a soldier under McGowan’s command after Desert Storm was hounded and detained for being “homosexual,” and McGowan’s own superior officer talked of ridding the Army of “faggots.”

McGowan did eventually come to terms with a fuller meaning of being a man: “I was also learning that it also meant having the integrity to accept who I was.” How this came about with a civilian lover in the next phase in his almost charmed life makes for a satisfying ending to his story, even though certain questions remain unresolved.

He’s careful to compliment himself for having been accepted and even popular—he was class president when at Fordham University, for example—but by “popular” he means fitting in with a group of men who are at times sexist and racist, and once even sadistic to McGowan during a now-banned Airborne hazing ritual. Why would a gay reader wish to be a part of this? How many gays will agree with McGowan that the “possibility of going to war was the most exciting thing I’d ever heard”?

The answer for some might lie in McGowan’s impassioned expressions of the spirit of men at war. From adolescence he had looked for a sense of belonging. In the military he found himself “becoming a part of a special community.” Even the physical surroundings of an Army post like Fort Sill, Oklahoma, provided that: “It had the feel of a very old, very prestigious and historic country club.” It was a club made up, not of older gentlemen playing golf, but of young men in uniform brimming with testosterone. McGowan reports without irony that “most of the time I truly enjoyed the company of the guys from the post; we’d bonded in a real way” by drinking and getting into brawls.

Fellow officers are described as “knuckleheads” until the orders for deployment, while enlisted men are called “sweet boys” until tested by war, which focuses them all on the professional task at hand: “My men needed my support and command. I had my job to do.” This leads to an almost mystical kind of love and sacrifice during combat: “I would do anything for these guys no matter what.” McGowan states that “I bonded with a group of men who, sexual orientation aside, seemed very like me.” His desire is that straight soldiers and U.S. citizens might one day be able to make this statement, as they do in other countries. For McGowan, the question of being a soldier and a gay man cannot yet be resolved in the U.S. military. The book ends with a plea to readers to help eliminate the “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy, something that will require backing from straight allies and a curtailment of the sort of animosity that McGowan felt during his time in the service.

Dan Luckenbill, a Los Angeles-based writer, was a U.S. Army artillery lieutenant in Vietnam.