Beneath the Skin: The Collected Essays of John Rechy

Beneath the Skin: The Collected Essays of John Rechy

by John Rechy

Carroll & Graf. 305 pages, $14.95

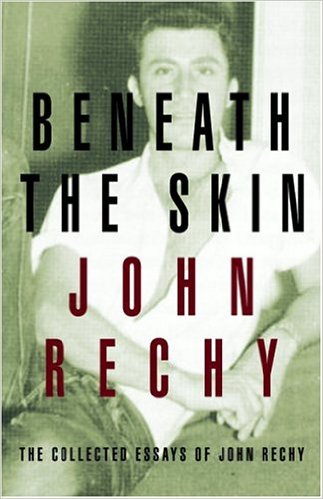

IN CHOOSING to show some of his own skin for the cover of his essays now collected as Beneath the Skin, John Rechy remains the consummate rebel. He appears shirtless and sexy with a cigarette dangling from the lips. The photo, by Lon of New York, who photographed mostly street-smart bodybuilders, evokes Rechy’s hustler creation in his classic 1963 novel City of Night. This persona now promotes his nonfiction as similar images of the French rebel intellectuals Jean Genet and Albert Camus promoted theirs. Rechy champions the works of these outlaw authors and others, such as Gore Vidal and Bret Easton Ellis, along with actors and even bodybuilders in these always provocative and often quite funny reviews, commentaries, lectures, and memoirs.

The rebel identity is not just a pose. Midway through this volume, in one of its most important essays, “The Outlaw Sensibility,” Rechy rejects the terms outcast and exile to assert with defiance that the outsider becomes an outlaw, and he proclaims himself one. In his earliest essays, Rechy stakes out the challenging territory of his nonfiction and critical works, beginning with his identity as a Chicano and a gay man. In a 1958 essay he admires the 1940’s pachucos of his native El Paso for their style: “[They] walked cool, long graceful bad strides rhythmic as hell, hands deep into pockets, shoulders hunched.” When Rechy assumes this style as a gay male hustler in 1950’s Los Angeles, it gets him into trouble with the notorious Los Angeles police, as he recounts in the 1959 essay, “The City of Lost Angels.” This essay, with its intriguing references to gay life in that period, including “a coffeehouse for teenage queers,” seems to be a rehearsal for City of Night in both style and subject matter.

Rechy states that choice is “an element shaping the outlaw sensibility.” And, since “intrinsic in the word ‘outlaw’ is the implication that the ‘laws’—the conventions—questioned are wrong, oppressive,” he has chosen to assume all the “dangers in asserting a proud, questioning alienation.” These essays assume a defiant stance toward anyone would put down Chicanos, gays, writers about Los Angeles, liberal thinkers on a variety of causes, and those who pursue widely derided preoccupations such as bodybuilding.

The book includes an enticing collection of memoirs, “Fragments from a Literary Life,” teasing in their brevity, but it is hoped that they will lead to further works of this kind. I heard many of these anecdotes firsthand, but now rather than table talk or talk from the writer’s study for a lucky few, they are published for everyone to enjoy. Full disclosure: I met John Rechy in the mid 1970’s through his now legendary teaching at UCLA. I had expected my stories of frank gay sexual encounters to be treated seriously in his class, and they were. Rechy conducted the classes on strict feminist principles. Everyone who wished to comment was given a turn around the table. Submissions were critiqued on the intent of the writer and not one’s own preconceived ideas of good writing. Harsh and potentially destructive back-and-forth dialogue was discouraged. When a student objected to the graphic content of my stories, it was he who quit the class, and not I.

Rechy’s sympathies lie with those who attempt and at times succeed in their own outlaw stances and difficult creations of the self. He extends these sympathies to actors like Marilyn Monroe and James Dean. He proclaims his admiration for a diverse and entertaining selection of writers, including the writers associated with Grove Press and “Beat”—Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William Burroughs—as well as for Kathleen Winsor, who receives a warm tribute in praise of her story-telling magic.

Rechy admires Jonathan Swift for the way in which “he wove suspense into the very syntax of a sentence, sculpting a precise, clear, yet complex prose.” He comments that Carson McCullers began her novel Reflections in a Golden Eye with “an impeccable paragraph of sculpted prose.” He lets Burroughs gently off the hook with the disclaimer that Burroughs “is perhaps in too much of a rush to reach his structural ends to bother always with handsome syntax.” In contrast, Rechy prides himself on being a stylist and a grammarian, qualities not always associated with the image of a street tough.

It is Rechy’s habit to pull no punches when exposing those he thinks are undermining or disvaluing his personhood as a gay man. He skewers homophobic and pompous politicians, heterosexual directors who demean gay and lesbian life, and actors like Tom Cruise who enforce their heterosexuality through court rulings.

He doesn’t let Joyce Carol Oates off the hook when he reviews her novel, Blonde, about his cherished Marilyn Monroe. His cunningly argued review shows Oates’s deficiencies through hilarious quotes of her sloppy writing. He decries her indefensible slurring of Los Angeles and her self-proclaimed assumption of Monroe’s persona. Oates has so offended Rechy that a student of his concocted a tea for him, presented in a glass jar with the palliative, even exorcising, label: “Soothing Joyce Carol Oates Begone Tea.”

The essays as compiled bring back early gay struggles now usually forgotten, from protests by Vietnam veterans against the war to the relentless drive within the GLBT community to present positive (primarily gay male) images. Some critiques are more dated than nostalgic. Rechy didn’t like early “heterosexual films in drag,” such as Birds of a Feather [La Cage aux folles], and on his website he critiques the similar pandering of Queer Eye for the Straight Guy. He notes that the long development of the GLBT movement in Los Angeles, beginning at least as early as the late 1940’s, is slighted in favor of endless analysis of a few nights in 1969 at the Stonewall Inn in New York.

At the time of celebration of the Lawrence v. Texas decision, in an essay first published in this journal (“Lawrence Brings It All Back Home,” Nov.-Dec. 2003), Rechy uses the occasion to recall the long history of abuse against gays and lesbians that one court act can’t sweep aside. The piece recalls an earlier commentary in which he excoriated the 1986 decision in Bowers v. Hardwick: “In a cold, almost mocking tone, the decision reads at times like a biased tract.”

But Rechy also locates prejudice within the gay and lesbian community, where things often came down to very fine distinctions. The emergence of the new macho gays in the mid-1970’s led to the virtual ostracism of their drag queen forbears. He proposes representing “a homosexual reality that doesn’t apologize for its rich sexuality or splendid variety—from musclemen to transvestites.”

Rechy’s nonfiction succeeds through his ability to engage the critical topics of the time, along with the unflinching moral stance he adopts. From his early prose poems in a 1950’s rock-n-roll style to a more classical yet original and always finely honed writing style, his nonfiction works predate and then develop along with the modern gay liberation movement. And all the while Rechy was producing in his novels, from City of Night to the recent The Life and Adventures of Lyle Clemens, a literary record of a subculture and a society in transition.

Dan Luckenbill, a writer and activist, works at the UCLA library.