Published in: May-June 2005 issue.

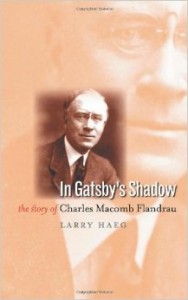

In Gatsby’s Shadow: The Story of Charles Macomb Flandrau

In Gatsby’s Shadow: The Story of Charles Macomb Flandrau

by Larry Haeg

University of Iowa Press

273 pages, $29.95

THIS IS the first published biography of Charles Flandrau, a novelist, critic, and short story writer for the Saturday Evening Post, called “the best essayist in America” by New Yorker drama critic Alexander Woollcott in 1935. Yet Flandrau is virtually forgotten today. He was born in St. Paul, Minnesota, in 1871, and the shadow to which the author alludes in the book’s title is that of fellow Minnesotan F. Scott Fitzgerald. Other than a minor guest appearance in The Beautiful and the Damned, there is little, other than geography, to tie the two together.