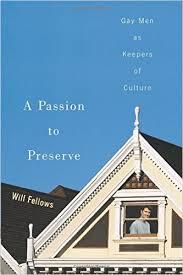

A Passion to Preserve: Gay Men as Keepers of Culture

A Passion to Preserve: Gay Men as Keepers of Culture

by Will Fellows

University of Wisconsin Press.

280 pages, $30.

Steve: We don’t have children.

Adam: We have taste.

— Paul Rudnick,

The Most Fabulous Story Ever Told

WILL FELLOWS’ A Passion to Preserve is really two books. One looks at living gay men who have devoted their lives to restoring and preserving old houses and other American antiquities. The other documents some similar men who did the same sort of work in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. Much of the contemporary material consists of oral histories in the manner of Fellows’ earlier book, Farm Boys (1996), and is fascinating to read.

Duncan Mitchel is a writer living in Bloomington, Indiana.