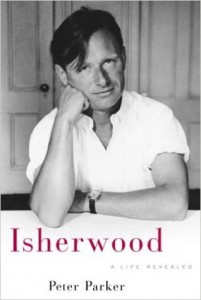

Isherwood: A Life Revealed

Isherwood: A Life Revealed

by Peter Parker

Random House. 815 pages, $39.95

DIARIES ARE curious things. They are private records, but when they document the lives of public figures, those divisions become murky. In the case of Anglo-American writer Christopher Isherwood (1904–86), whose diaries exceed a million words—hundreds of thousands of which have already been published—they can be downright damning. And so they often are in a new biography that will, for better or worse, be the definitive biography of one of the most important literary chroniclers of the 20th century.

Chris Freeman is co-editor, with James Berg, of The Isherwood Century (2000) and Conversations with Christopher Isherwood (2001).