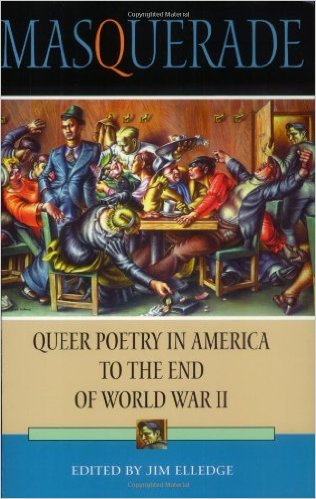

Masquerade: Queer Poetry in America

Masquerade: Queer Poetry in America

to the End of World War II

Edited by Jim Elledge

Indiana University Press

464 pages, $65.

EVEN the erudite student of gay writing will find previously unknown poets anthologized in Masquerade. I love the obscure, so I had heard of Charles Hanson Towne, George Sylvester Viereck, and Adah Isaacs Menken, although admittedly I had never actually read any of their poetry. But the names of Wilbur D. Nesbit, Persis M. Owen, and David and Rose O’Neill (no relation, although born in the same year, 1874) are absolutely new to me. Somewhere along the line I might have heard of Rose O’Neill, but as the “inventor of the Kewpie doll” (did such a thing need to be invented?) and not as a poet. Of course, from a literary standpoint, there’s no reason to have heard of Rose O’Neill, whose verse, at least the sampling Jim Elledge brings to our attention, is decidedly unexceptional. A contemporary of Gertrude Stein (who was also born in 1874), one of her poems to a woman writer ends:

She wrote it! She, my lyric you!

You beat of drum, you lull of lute!

You voice of cataract and dew,

You verse, you violin, you flute!

You roar! You sound of loves that sue!

Tongue of the world, who pierce and coo!