IN HER 1993 BOOK on Jared French (1905-1988), the first devoted entirely to this painter, Nancy Grimes remarks on the interpretive difficulties that spring from the painter’s private symbolism, difficulties compounded by our inadequate knowledge of his life: “Jared French’s life is nearly as obscure as his paintings. Two of the people closest to him, his wife Margaret, and Paul Cadmus, share a reticence that was also natural to French. Public records establish a rough biographical outline, but no diaries, letters or memoirs by intimate friends have emerged to fill the gaps.” Inadequate though it may be, I propose to use that “rough biographical outline” (and the triangular liaison it so clearly embodies) as a key to the mysterious figures that populate the artist’s work.

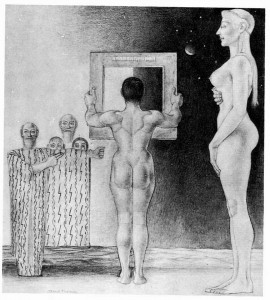

There is a pointed, choreographic disposition of male and female figures in a good many of French’s pictures, and this spatial presentation of gender and sexual orientation offers a promising entrée into what seems to be a cryptic system of symbols. Let’s start with the pencil drawing Examination and Interpretation (1943), which presents a kore-like woman in the right-hand

Pencil on paper. 10-1/4” x 9-1/8”. Private collection.

foreground against a night sky and a smaller male figure in the sunlit left-hand zone of the composition. Behind the sleeve that falls from his hieratically raised left hand is a triad of faces, his own again and that of a male (on his left) and a woman (on his right). Since the male is bald and white-bearded, and wearing a robe inscribed with a quasi-runic pattern (traditional features of a magician), and since he is placed in the luminous zone of the composition, he would seem to represent the principle of wisdom, forming a stable triangular pattern with male and female, and sanctifying that stability with his right hand poised in benediction. The idealism of this resolution is hinted at by the fact that none of the three faces appears to be attached to a trunk: no feet are visible in the gap between the sleeve and the ground. Between these antithetical spaces of light and dark there is an androgynous figure with the musculature of a male but the hips and buttocks of a woman. He/she holds up a frame in which the light (male) and dark (female) zones of the background are differentiated by a sharp vertical line. Art, so the allegory implies, affords clarity by simplifying complex surfaces into patterns (its resource of stylization), and mirrors the androgyny of the central figure in its diagrammatic bisection of dark and light.

In the undated tempera panel entitled The Strange Man, there’s also a stable triad of figures—in this case two dark males and a pale female, triangulated across a pale manikin whose rigid posture suggests his reluctance to be presented to the woman. She is dressed in an androgynous garment, half trouser-suit, half Cretan dress, a detail that connects her to the Minoan figurines of the Snake Goddess. Even though those phallic creatures do not figure in French’s design, one remains half conscious of their absence—a sort of intellectual pentimento. R. W. Hutchinson (1962) has pointed out, moreover, that the snakes in question were probably emblems of domesticity: “It was the house snake that was fed and revered as the genius, the guardian angel of the house, according to a very widespread superstition.” More to the point, the woman’s Cretan décolletage displays a breast that she seems to be gathering up for the mouth of a reluctant subject, who (one assumes) will stand upright once nurtured by her milk of domesticity.

In Two Standing Nudes (pencil on paper, 1945), the manikin occurs in a vertical position, its doll-like incapacity registered by the tilt of the head—a detail that French might well have taken from the ballet Coppélia, where it is used to identify the mechanical nature of the doll. (We shouldn’t forget the artist’s connections, through the brother-in-law of Paul Cadmus, with Ballet Caravan, who designed the décor for Billy the Kid in 1938.) Indeed Cadmus would later incorporate manikins into one of his compositions: in Manikins (1951), two marionettes (presumably male) “copulate” on a copy of Corydon, André Gide’s famous apologia for homosexuality. The advantage of this displacement of human by artificial figures is that of metonymy: it can hint at controversial relations without depicting them explicitly. That there would have been a major scandal in 1951 if Cadmus had painted coupling men instead of manikins can be gathered from E. M. Forster’s comment upon it and The Bath (1951), a genre scene in which two males are shown sharing a bathroom: “Enjoyed your two wooden puppets and still more your two human ones. Rather wish the two compositions could have been reversed—the wooden puppets showing … and the … But it wouldn’t have done.” [Ellipses present in Forster’s text.]

Returning to Two Standing Nudes, we can see that the slack, dependent posture of the smaller of the two men is offset by the natural stance of the larger, and it is the latter who supports (and by implication controls) his marionette-like partner. Similarly, in Washing the White Blood from Daniel Boone (1939), Boone is being held up by five Native American figures, whose skin tones recall those of the two dark men in The Strange Man. The mauve scarf wrapped around Boone’s left arm is held by the chief celebrant, and his hands rest lightly on the shoulders of two other acolytes. This stance recalls the posture of some crucifixes of the Eastern Orthodox tradition in which the corpus, far from hanging on the cross as a pendant of suffering, has its arms aligned with the transverse beam and reigns from its martyrdom as Christos Pantakrator. Although he is more self-possessed than the subsidiary figure in Two Standing Nudes, Boone is nevertheless in a position of dependence. French uses a swathe of fabric to attach him to one of his acolytes, an emblematic bondage that will recur in later pictures.

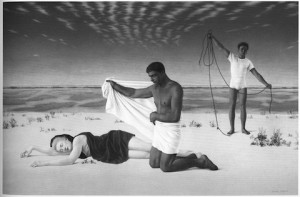

One of these is Figures on a Beach (1940), about which Nancy Grimes offers the following analysis:

Private collection. Courtesy D. C. Moore Gallery.

Even the sleeping woman … seems to exert a magical influence on the two young men who attend her. Her head covered by a purple hood, her pale body partially covered in a blue cloak, she seems to have come from the sea, exposed by the receding tide or perhaps fished out by the youth with the rope. Kneeling beside her, another young man solemnly covers his own nudity with a white towel, as though suddenly overcome by modesty in the woman’s presence. Here, French’s woman suggests both Mary, the Virgin Mother, and Artemis, the virginal goddess of the Greeks who tamed beasts and demanded chastity from her companions.

While this provides a plausible account of the composition, its components can sustain a very different interpretation if we cross-reference it with The Rope (tempera on gesso, 1954). This painting depicts a scene in a swimming pool with three naked young men attached through controlling ropes to older ones—an allegory, most likely, for one kind of homosexual relationship. The ropes might well be the allotropes of puppet strings, even if the dependent manikins in Two Standing Nudes and The Strange Man are stringless. Because we know that French deeply admired the work of D. H. Lawrence, we could explain this notion of bondage by invoking Women in Love:

Suddenly he saw himself confronted with another problem—the problem of love and eternal conjunction between two men. Of course this was necessary—it had been a necessity inside him all his life—to love a man purely and fully. Of course he had been loving Gerald all along, and all along denying it.

He lay in the bed and wondered, whilst his friend sat beside him, lost in brooding. Each man was gone into his own thoughts.

“You know how the old German knights used to swear a Blutbruderschaft,” he said to Gerald, with quite a new happy activity in his eyes.

“Make a little wound in their arms, and rub each other’s blood in the cut?” said Gerald.

“Yes—and swear to be true to each other, of one blood, all their lives. That is what we ought to do. No wounds, that is obsolete. But we ought to swear to love each other, you and I, implicitly, and perfectly, finally, without any possibility of going back on it.”

He looked at Gerald with clear, happy eyes of discovery. Gerald looked down at him, attracted, so deeply bondaged in fascinated attraction, that he was mistrustful, resenting the bondage, hating the attraction.

Birkin differentiates this homoerotic bond from heterosexual attraction, which he conceives as something that ideally is non-compulsory:

On the whole, he hated sex, it was such a limitation. It was sex that turned a man into a broken half of a couple, the woman into the other broken half. And he wanted to be single in himself, the woman single in herself. He wanted sex to revert to the level of the other appetites, to be regarded as a functional process, not as a fulfillment. He believed in sex marriage. But beyond this, he wanted a further conjunction, where man had being and woman had being, two pure beings, each constituting the freedom of the other, balancing each other like two poles of one force, like two angels, or two demons.

He wanted so much to be free, not under the compulsion of any need for unification, or tortured by unsatisfied desire. Desire and aspiration should find their object without all this torture, as now, in a world of plenty of water, simple thirst is inconsiderable, satisfied almost unconsciously.

The “broken half of a couple” might well have supplied French with his imagery of imperfect relationships—the fragile manikins in A Strange Man and Two Standing Nudes—as though he were hinting at an inherent imperfection or instability in same-sex relationships. Birkin develops the idea at some length:

And why? Why should we consider ourselves, men and women, as broken fragments of one whole? It is not true. We are not broken fragments of one whole. Rather we are the singling away into purity and clear being, of things that were mixed. Rather the sex is that which remains in us of the mixed, the unresolved. The passion is the further separating of this mixture, that which is manly being taken into the being of the man, that which is womanly passing to the woman, till the two are clear and whole as angels, the admixture of sex in the highest sense surpassed, leaving two single beings constellated together like two stars.

Each acknowledges the perfection of the polarized sex-circuit. Each admits the different nature in the other.

French’s pictures allegorize sexual options in images of irresolute transition in much the same way. Take, for example, the boy on the windlass in Woman and Boys, in which the artist seems to be saying that “the sex is that which remains in us of the mixed, the unresolved.”

Returning to Figures on a Beach, we can now read the rope-wielding youth in the background as the lure of homosexual attachment, which is based on coercive “bondage” as opposed to the comparatively “spontaneous” heterosexual desire embodied in the kneeling figure. Whereas Grimes assumes that he is clothing himself, one could just as plausibly conjecture that he is about to remove his loincloth—more plausibly, perhaps, when we recall that the composition is partly based on Piero di Cosimo’s Mythological Subject (National Gallery, London) and on Correggio’s Terrestrial Venus (Louvre). In both, the recumbent female figure is balanced by a vigilant satyr, tender in the first case, lustful in the second. His “natural” attraction to the woman is about to be countervailed by the coercive youth, who will rope him in for himself. The displacement of the satyr by a man becomes even more significant if we remember how both French and Cadmus associate goats with masculine sexuality.

French’s early Mallorcan Quarry (1932) surmounts its homoerotic grouping of laborers with two goats (Grimes reads them as donkeys), while Cadmus in Ruban Dénoué (1963) places Reynaldo Hahn between an aerial pixie and a lusty Pan. (The freedom of the ribbon that billows toward the moon might even be Cadmus’s pro-homosexual response to his lover’s constrictive use of rope.) The fact that the woman in Figures on a Beach bears a faint resemblance to Margaret French and the man to the homosexual photographer George Platt Lynes might reflect French’s limited pool of models, or it might constitute a deliberately autobiographical tableau à clef.

Four years later French would paint Woman and Boys, where the same woman in the same Marian cloak now stands in the foreground, left of center, while two youths romp on the right-hand side of the composition. One of these carries the leitmotif of the rope—homoerotic bondage by compulsion—and a net, the other a pronged stave. The presence of the net in the hand of the blond youth tempts us to read it as the trident of the Roman gladiator (the retiarius was equipped with trident and net), and thus to give a combative value to the interaction these two figures may be poised to undergo. A third youth on the left seems torn between the heterosexual and homosexual options, for his gaze traces a path between them, even though the windlass on which he is balancing suggests an affinity with the rope-carrying figure.

State Park (1946) may also dramatize an opposition between homosexual and heterosexual options. Here are depicted a lifesaver who carries a phallic baton and a markedly phallic whistle around his neck, and a pale-skinned boxer on the other side. The two male figures, shown in stiff contrary motion, are exposed to the midday sun. Their manifest discomfort is contrasted with the apparent contentment of a nuclear family, presented as a self-sufficient circle beneath the shade of an umbrella. It is no doubt significant that French has allowed the toes of the father’s right foot to stray beyond the boundary of shade, giving him a faint connection to the more abrasive potentiality of the relationship outside the shelter.

The contrasting skin tones of the lifeguard and the pugilist are recapitulated (or anticipated) in Help, painted on ivory in the same year. Here a pale man has rescued a bronzed one from the sea and is bearing his stiff, manikin’s body out of the water. While tanned skin usually represents athleticism, here French makes pallor the attribute of the savior. Perhaps it encodes an autobiographical reference, for in all Paul Cadmus’s paintings of French and himself, Cadmus is shown to take the sun well, while French’s body is typically presented in pink tones. We see this, for example, in Cadmus’s The Shower (1943), where a female figure (unquestionably Margaret French) is placed at a distance from two men, the sun-browned one slouched against the shower wall, the pink one in the process of lathering himself. The lather, which has the spattered consistency of semen, has escaped beneath the partition and is traveling toward the buttocks cleft of the tanned figure—almost certainly a reference to the sexual bond between the two figures. Even though their faces are not shown, they can be identified as Cadmus and French by the presence of the latter’s wife as she looks on non-judgmentally in her Marian drape of blue and white. The Fire Island “Pajama” photographs that the members of this trio took of each other in the 1940’s supply external evidence for that identification, as does Cadmus’s What I Believe (1948). Here a very pink French (with his face fully visible) has his hand around a yellow-brown Cadmus (also clearly identifiable), while Margaret French, standing behind them, includes both in her benedictory embrace.

The complementarity of pale and dark skin might suggest a temperamental balance between two men. (Cadmus was almost certainly a Kinsey 6, French a 3 or 4.) It can also be related back to the presence of the Native Americans grouped around the cruciform figure in Washing the White Blood from Daniel Boone, as well as to the African-American figure that French has placed in The Double (ca. 1950).

Nancy Grimes has provided a most impressive and authoritative reading of this mysterious picture:

The narrative is ambiguous. The central figure, a handsome, pallid youth, completely naked, is either about to rise from or sink into a shallow grave. He is watched by his double, a rather fussily dressed figure in turtleneck and hat, who kneels with his thighs pressed tightly together and one palm upturned, as though urging his twin to rise. Sitting on a fence at a slightly higher level (here again, French uses different physical levels or heights to indicate varying states of physical growth), a young black man, half-dressed, relaxed and uninhibited, sits with hands cupped between open thighs. Behind this group, to the left, lurks a funereal specter, a woman in dark Victorian dress and a phallically feathered hat. This ominous figure, compositionally linked to the pillars of industry on the horizon, stands ready to place a blood-red leather wreath on the grave, but, smaller and placed at a distance from the others, she seems to belong to the past.

Certainly the painting alludes to the conflict between Victorian values, in retreat yet still influential, and a younger, more open generation. But the three young men also represent varying states of spiritual and sexual freedom, with the unclothed youth, monumental and erect, representing the naked or unrepressed self arrested midway in its upward passage from the unconscious to consciousness.

This construction takes on additional subtlety in the context of other paintings by French. Just as Blake offered two contrasting points of view in Songs of Innocence and Experience, French now offers an entirely different take on the homo/hetero dialectic from that of Figures on a Beach. Two thirds of the later painting are devoted to male images of freedom and invitation, while in the remaining third, and on the “dark” side of the profiled nude, a woman is now carrying the coercive “lasso.” This masquerades as a life-buoy (hence its unnatural red), but is actually a funeral wreath. Likewise her protective umbrella, unlike the one that shelters the heterosexual family in State Park, has been given a gothic, bat-like formation. Its blackness, furthermore, is the traditional color of a rain umbrella, not a parasol. Like the jays in Richard Wilbur’s “From the Lookout Rock,” she thus “makes a patch of storm.” A feather—regarded by Grimes as “phallic”—assumes the sinister formation of a hooded cobra. In like manner, among the semi-abstract works of French’s last phase is a picture entitled Animus Anima (1968-69). Here the phallic animus (an erect penis with a facial glans) is colored white and blue, enwreathed with a sepia buttocks and arm, and approaches an anima similarly differentiated by terracotta and white zones, its vaginal opening created from two interlocking male figures (a distant recollection, perhaps, of the wrestling scene in Women in Love).

Evasion (1947) also seems to place the notion of the Doppelgänger in a context of sexual allegory. The one double is nude (and painted twice over), the other clothed from neck to ankle in blue. All three figures are in postures of shame and supplication as if apologizing for their homosexuality. In the background, they diverge up separate staircases, duplicated in the distance in what might be an infinite series of evasions. A mirror is placed quite out of reach of the kneeling figure, who perhaps represents religious conformity, but close at hand to the nude man, who nevertheless prefers to avoid it.

It seems safe to conclude that Jared French used his paintings in part to resolve his feelings about his sexual orientation. We must remember the moral climate of the 1940’s and 50’s and the pariah status generally accorded to homosexuals. One character in Mary Renault’s The Charioteer (1953) remarks on the discrepancy between the homosexuality exemplified by the likes of Michelangelo and its debased approximations in the contemporary scene. And even Paul Cadmus, who seems never to have agonized over his sexual orientation, nonetheless “paints out” (in the sense that an author might cathartically “write out”) aspects of the community of which he forms a part, but about which he feels misgivings. In his Y.M.C.A. Locker Room, for example—an oil on canvas executed in 1933—he incorporates exploitative couplings of youth and age that anticipate comparable alignments in French’s Rope, and even twenty years later, in Bar Italia, he depicts what he has called “a group of rather outrageous gays in the left-hand corner.” It is clear from the gestures that the men in question are discussing penis size, and yet—a wryly honest gesture—Cadmus shows himself leering at the crotch of the Italian youth who lolls on the parapet (noting later that “I appear in it myself in a not very flattering way”). These social tensions would no doubt have been exacerbated for a man like French, whose orientation was not wholly homosexual.

There are many literary instances of liaisons in which the bisexuality of one partner has a disruptive effect on the bond. In Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man (1964), the narrator observes, “Woman could only be fought by yielding, by letting Jim go away with her on that trip to Mexico. By urging him to satisfy all his curiosity and flattered vanity and lust (vanity, mostly) on the gamble that he would return again (as he did).” A parallel event occurs in Joseph Hansen’s A Smile in His Lifetime (1981), which is set, like Isherwood’s novel, in the 60’s: “Brown, naked Kenny and a pale little girl, fucking on a blanket. Kenny is reaffirming his manhood. He overheard someone at Kate’s party say he was a faggot. He had to be, didn’t he—living with Whit Miller.” In the absence of any specific biographical information to the contrary, we can assume that French’s decision to marry in 1937 was prompted by a similar division within himself, a division like that in D. H. Lawrence and externalized in Birkin’s stress on loving a man “purely and fully”—loving a man, that is, not as depicted in paintings like YMCA Locker Room or Bar Italia, but in a way that made this love ancillary to the traditional structure of heterosexual marriage.

There is prima facie evidence that the dialectic shifts, and adjustments in his iconology were part of this effort, especially if we recall the serene triad of Margaret French, the artist and the browned Paul Cadmus in Music (1943). Here the ropes of coercion have been harmonized into musical strings, and the anima and animus affirmed and incorporated by the plumb lines that indicate the oppositional poles of the design, hanging in unprotesting acknowledgement of their mutuality and interdependence.

References

Grimes, Nancy. Jared French’s Myths. Pomegranate Artbooks, 1993.

Hansen, Joseph. A Smile in His Lifetime. New American Library, 1981.

Hutchinson, R. W. Prehistoric Crete. Penguin, 1962.

Kirstein, Lincoln. Paul Cadmus. Pomegranate Artbooks, 1992.

Lawrence, D. H. Women in Love. Viking Press, 1922.

Rodney Edgecombe, associate professor of English at the University of Cape Town, has written ten books on topics in music, art, and history.