Gay Voices of the Harlem Renaissance

by A. B. Christa Schwarz

Indiana University Press

209 pages, $21.95 (paper)

The Splendid Drunken Twenties: Selections from the Daybooks, 1922–1930: Carl Van Vechten

Edited by Bruce Kellner

University of Illinois Press

328 pages, $34.95

The Collected Writings of Wallace Thurman:

A Harlem Renaissance Reader

Edited by Amritjit Singh and

Daniel M. Scott III

Rutgers University Press

509 pages, $30 (paper)

THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE began in the early 1920’s and ended some ten or fifteen years later, depending on whom you ask. That short time span saw the emergence of writers, artists, art collectors, and bon vivants of all colors, genders, and sexual orientations. There’s still a lot that we don’t know about the era’s gay writers, in part because they were so closeted or, at best, ambiguous about their sexual orientation.

The only openly gay (though married) writer, Richard Bruce Nugent, was not considered one of the major figures of the Harlem Renaissance, but he is renowned for his tale, “Smoke, Lillies and Jade,” the first gay short story by an African-American writer, which was published in the magazine Fire!! (edited by Wallace Thurman, author of the 1932 novel, Infants of the Spring). Nugent’s life and work were discussed by Thomas H. Wirth in his Gay Rebel of the Harlem Renaissance (2002), which I reviewed in this journal (Nov.–Dec. 2002). Little attention has been paid to date to the work of the lesbian, bisexual, or orientation-unknown women writers of the Renaissance, such as Nella Larsen and Angelina Weld Grimké. As Christa Schwarz writes in Gay Voices of the Harlem Renaissance, referencing sociologist bell hooks: “lesbians were viewed as particularly deviant” because they would not be participating in child-bearing. In the milieu of Harlem, Schwarz notes, gay men were slightly more acceptable than lesbians.

While the three books under review here are all published by university presses, Schwarz’s is the most scholarly, with fifty pages of notes and references. Much easier to browse than read straight through, she comes up with fascinating nuggets of information not found in other sources. She concentrates on four writers, Langston Hughes, Nugent, Countée Cullen, and Claude McKay, with chapters that describe Harlem both as a cultural center and as a “sexual pleasure center.”

Countée Cullen, who admired Keats and Tennyson, was regarded as the “poet laureate” of the Renaissance and was “apparently never

sexually involved with a woman,” though he was married twice, the first time to W. E. B. DuBois’ daughter, and on his honeymoon went abroad with Harold Jackman. Poet and novelist Claude McKay, who was bisexual, was born and raised in Jamaica and spent the latter half of the Renaissance years in Europe and North Africa. Schwarz notes that some scholars debate whether he was a true member of the Renaissance due to his absence, place of birth, and his “focus on the black working class.” His novels dismissed or disparaged lesbians, while he wrote in fairly tolerant terms about gay men.

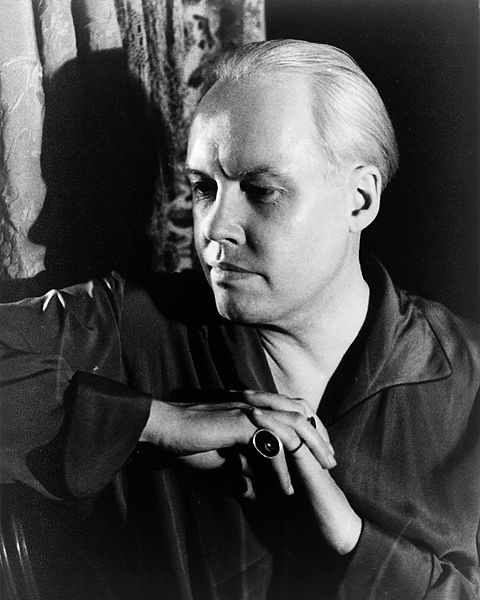

Bruce Kellner first met Iowa-bred Carl Van Vechten when Kellner was 21 and Van Vechten was fifty years older. He knew Van Vechten for thirteen years, and this deep knowledge has produced The Splendid Drunken Twenties, a beautifully illustrated book, full of photographs and caricatures by Miguel Covarrubias. The entries cover 1922 through 1930, during which time Van Vechten published seven novels. Before he became a novelist, he was a music critic and then a drama critic for New York newspapers, after which he wrote essays and articles. What emerges, finally, is a man of many contradictions. He promoted such writers as Gertrude Stein and Ronald Firbank as well as non-Renaissance African-American writers; his apartment was called “the downtown office of the naacp.” By late 1924, he had begun his “one-(white)-man campaign to spur what has come to be called the Harlem Renaissance,” and recommended Langston Hughes to his friend, publisher, and upstairs neighbor, Alfred Knopf.

Van Vechten was a mean drunk, often beating up his wife, actress Fania Marinoff, and documenting that fact in his daybooks. At those times, she would take refuge at the Knopfs’s. He insulted his friends when he was drunk and didn’t understand that even apologies and flowers wouldn’t mend a long-term rift. He indulged in anti-Semitic slurs. He refused to change the incendiary title of his Nigger Heaven (1926), whose publication resulted in “a fierce backlash in the black press.” W.E.B. DuBois recommended that it be burned.

Kellner has done an extraordinary job with Van Vechten’s nearly illegible and often cryptic entries, furnishing background data whenever a new name or place is introduced. Van Vechten mentions what he’s reading, what he thinks of it, where he lunched and with whom, who came for dinner, and where he partied. Ben Neihart’s 2003 novel Rough Amusements: The True Story of A’Lelia Walker, Patroness of the Harlem Renaissance’s Down-Low Culture offers a remarkable portrait of the buffet flats, dives, clubs, and mansions where parties of all sorts ran all night long, and where Van Vechten was a frequent guest. The Van Vechten marriage, Kellner notes, was “interrupted sporadically by homosexual liaisons.” Actor and designer Donald Angus was one of his lovers, from 1919 to 1929, and sporadically for many more years. By the end of the diary, Van Vechten has decided to try his luck in Hollywood; his brother dies, leaving him a millionaire.

Much more sober is the Collected Writings of Wallace Thurman, by English professors Amritjit Singh and Daniel M. Scott III. This book is obviously aimed at college students in literature courses, though the editors hope it will appeal to the general reader. It includes the texts of Thurman’s previously uncollected writings and unpublished manuscripts, essays, plays, and letters. This potpourri includes letters to Langston Hughes, among other writers. These are delightful and full of literary gossip. In 1929, he wrote: “Claude [McKay] I believe has shot his bolt. [Thurman found McKay’s Banjo (1929) “turgid and tiresome”] … Counteé [Cullen] should be castrated and taken to Persia as the Shah’s eunuch. … Bruce [Nugent] should be spanked, put in a monastery and made to concentrate on writing.” In a 1930 letter to Harold Jackman, he wrote of Carl Van Vechten’s seventh novel Parties that he “did not like Carl’s latest effusion. Frankly I believe it to be his worst novel to date. All of his limitations are relentlessly exposed.” (Parties was uniformly panned. Thurman had met Van Vechten in 1926, when Langston Hughes introduced them.) Unfortunately, unlike Kellner, editors Singh and Scott do not put Thurman’s dropped names in any sort of literary or historic context, nor do they give any historic context for Thurman’s book reviews.

A Midwesterner like Carl Van Vechten, Thurman began school in Idaho and as a child lived in Chicago, Nebraska, and Salt Lake City, where he finished high school. After a brief sojourn in California and as a pre-med student at the University of Utah, he arrived in Harlem in 1925. Thurman, who was a magazine editor, promoted and published the works of his friends. The editors state that “Thurman lived a self-described ‘erotic, bohemian’ lifestyle,” and “his close friends and roommates know him to be bisexual.” Although married, it was apparently a marriage of convenience, and divorce proceedings quickly ensued. His lover was a Canadian, Harald Jan Stefannson, who served as a model for characters in two novels. Thurman died of tuberculosis in 1934 at City Hospital on Welfare Island in New York, an institution of Dickensian squalor that he had disparaged in his 1932 novel The Interne, co-written with Abraham L. Furman, the publisher’s brother. Managing to squeeze as much life out of his few short years as he could, he spent a few of his later years in Hollywood writing screenplays for producer Bryan Foy, to whom he had been introduced by Furman.