The possibility that Abraham Lincoln had sexual relations with other men has been broached in the past, and new research is tending to corroborate the thesis that he did. As one might expect, many Lincoln scholars are bitterly opposed to this view, so it is perhaps not surprising that there’s been a recent flurry of interest in Lincoln’s relations with women. Beneath this renewed preoccupation with Abe’s heterosexual dalliances, then, there lurks a subtext that has everything to do with his homosexual ones. — The Editor

OVER THE LAST DECADE of the 20th century, a curious development unfolded within the Abraham Lincoln industry. Ann Rutledge: Remember her? According to legend she was the great love of Lincoln’s life. But she died tragically young, and poor Abe, himself only in his mid-twenties, never fully recovered; hence his famous melancholy. The tale’s theme of doomed high romance riveted the public. Many Lincoln biographers writing in the decades after his death accordingly featured it. By the late 1920’s, however, some scholars began to take a dim view of what they saw as a maudlin distortion of Lincoln’s life.1 J. G. Randall, the pre-eminent Lincolnist of his time, in 1945 delivered the final blows. With a brilliant and celebrated essay, “Sifting the Ann Rutledge Evidence,” he genteelly hacked the legend to death.2 Ann lived on in the popular imagination. But from Randall’s verdict forward, the legend was banished from the academy.

Then came the curious development. In 1990, Ann started to make a comeback.3 As the 90’s progressed the romance appeared in increasing numbers of serious articles and books on Lincoln’s early life, not as a “legend,” but as a major event for which there is “overwhelming evidence.”4 Today, the legend throbs on at full throttle in academia, to the point where one can go to a bookstore, check the index pages of almost any current Lincoln book, and there find Ann: reinstated as the girl whose death drove Abe to the brink of madness.

What happened? The discovery of compelling new evidence? No, the evidence concerning Lincoln and Ann Rutledge has been available to scholars for a very long time.5 Did J. G. Randall and other legend skeptics misinterpret that evidence? The opinion here is, No. They did not. So what’s going on in Lincoln scholarship? Short answer: a scandal.

Some Background to the Scandal

In 2000, the late C. A. Tripp6—psychologist, sex researcher, close associate of Alfred Kinsey, and author of the groundbreaking The Homosexual Matrix (1975)—enlisted me to help him complete a study of Lincoln’s personality and sexuality.7 One of the first things Dr. Tripp asked me to research was the material behind his draft chapter on Ann Rutledge. I rummaged through Dr. Tripp’s vast Lincoln computer database (the largest in the world). The more I looked into the legend, the more peculiar its revival seemed to become. Some months later, Dr. Thomas F. Schwartz, Illinois State Historian and an editor of The Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association (JALA), the premier Lincoln journal, expressed interest in publishing an adaptation of Dr. Tripp’s Rutledge chapter. At our request, Dr. Schwartz generously sent stacks of obscure material relating to New Salem, Illinois, the tiny village where the alleged romance took place. We also received abundant material on the Rutledge family.

No smoking gun lay within the documents. But they did shed light on a small mystery concerning Rutledge family reminiscence about Lincoln and Ann, the fine points of which, as far as I know, never until now have been discussed in print. Nor are they discussed in Dr. Tripp’s forthcoming Lincoln book. The main focus there is not on Rutledge memories, but on the question of Lincoln’s “grief” following Ann’s death, and on the one seemingly definitive item of testimony affirming a Lincoln-Ann romance. The latter came from a New Salem-era (1830’s) friend of Lincoln’s named Isaac Cogdal. Cogdal claimed that shortly before President-elect Lincoln left Illinois for Washington, he talked with Lincoln about Ann Rutledge. The claim carried heft, because all other testimony about Lincoln and Ann came from people who called up memories from the mid-1830’s. These memories weren’t recorded until after Lincoln’s death and therefore were at least thirty years old, in some cases far older. Cogdal’s testimony also was recorded after Lincoln died, but his alleged conversation with Lincoln was only some four or five years old.8 Hence, there seemed to be freshness, and therefore credibility, in Cogdal’s claims compared to those of others. Indeed, all champions of the legend point to Cogdal as the clincher proving that Abe and Ann were deeply in love.

But the legend’s scholarly legitimacy is beginning to crack. One prime indicator is the recent conversion of Lincoln luminary David Donald to an anti-legend stance. In his superb first book, Lincoln’s Herndon (1948), Donald had ridiculed the legend. In 1995’s Lincoln he reversed himself and, following the trend among most major Lincoln scholars, supported the legend, albeit with the canny proviso, “if Cogdal’s memory can be trusted.”9 In 2003’s “We Are Lincoln Men”: Abraham Lincoln and His Friends—what a title!—Donald reversed himself yet again. His grounds? In part, he writes in the current book, because of Dr. Tripp’s JALA article.10

These Cogdal particulars merely provide context. Readers interested in more about them can look up the JALA piece or wait for the publication of Dr. Tripp’s book, which, if fate is kind, will come in late 2004. The focus here is on a small subset of reminiscence about Lincoln and Ann from New Salem-era people who personally knew both parties: the recorded memories of members of the Rutledge family. Legend revivalists accord great importance to their testimony. As Douglas L. Wilson, revivalist-in-chief, put it: the Rutledges had an “opportunity to know.”11 Indeed. Let’s take a look. What did the Rutledges know?

Herndon’s Informants—And What They Told

Credit for what is known about what the Rutledges knew goes to Lincoln’s longtime law partner, William H. Herndon, a key figure in Lincoln historiography. Following the assassination, Herndon zealously tracked down people with personal knowledge of Lincoln’s early life to get statements from them. He accumulated a

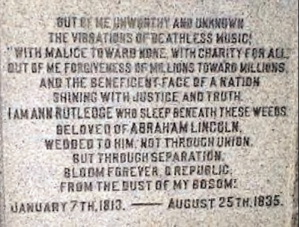

Ann’s remains were moved to Oakland Cemetery near New Salem, Illinois.

This tombsone was erected bearing an epitaph from the poet Edgar

Lee Masters. After some rhetorical flourishes, including a quote from Lincoln’s

Second Inaugural Address, it reads: “I am Ann Rutledge who sleep

beneath these weeds, Beloved of Abraham Lincoln, Wedded to him, not

through union, But through separation. Bloom forever, O Republic, From

the dust of my bosom! January 7th, 1813.—August 25th, 1835.”

huge mass of documents, now mostly housed at the Library of Congress in the Herndon-Weik Collection. Herndon’s research provides the main foundation for biography of the early Lincoln. But Herndon has another, more controversial, claim to fame, for it was he who launched the Rutledge legend.12 There is no need to describe here the histrionic and often hilarious way that he did it, except to say that he made waves, big ones, that did not quiet until Randall temporarily killed off the legend in 1945. The important thing is that Randall and others were also gunning for Herndon’s reputation, and with it, far bigger game: the entire tradition of amateur, reminiscence-based history. The “personal,” the “subjective” became suspect; respectable history required verifiability, which meant public, impersonal, documented facts. The treasure-trove that was Herndon was consigned to a vault.

A barely penetrable vault, at that, for only the most dogged scholars could decipher the fading documents. A microfilm record was made, but it too is hard to read. In 1998, however, the publication of Herndon’s Informants, a carefully prepared transcription of all the known statements, interviews, and letters about Lincoln that Herndon collected, made the collection easily accessible.13 Douglas L. Wilson, the aforementioned chief Rutledge-legend revivalist, and Rodney O. Davis edited Herndon’s Informants. A work of inestimable value, it has transformed scholarly studies of the pre-presidential Lincoln. Moreover, it is the major monument to a sea change in how Lincoln history is done: the rehabilitation of reminiscence-based evidence.14

An advocate of “oral history,” or history based on reminiscence, Wilson found in the Ann Rutledge controversy a way to make the case that personal memories, even of events very distant in time, offer perspectives that historians must take seriously. Wilson charged that J. G. Randall, with “Sifting the Ann Rutledge Evidence,” wrongly disparaged what Herndon’s informants remembered about Lincoln and Ann. “James G. Randall’s most pervasive contention,” Wilson wrote, “is that the testimony of Herndon’s informants is dubious because it is subject to the notorious fallibility of human memory.”15 A page later, Wilson cited comments from one “Aunt” Louisa Clary, who as a child had lived in New Salem. Much later in life Louisa impressed a Lincoln researcher, Thomas P. Reep, with her seemingly near-photographic memory of the layout of the village, which by then had nearly vanished due to economic failure, abandonment, and the ravages of nature. Reep asked Louisa, “How in the world is it you can remember these things and locate these places so closely?” Louisa replied, in part: “In all these years my mind has kept the picture fresh by frequently having it recalled to me.” She was referring to things she had heard from family and friends about the olden days in New Salem. Wilson noted: “For many of Herndon’s informants, and for much of their testimony about Lincoln as a young man, keeping the picture fresh by frequently having it recalled to them would seem a more apt characterization than Randall’s ‘dim and misty with the years.’”16

That is how Randall had characterized the Rutledge family’s Lincoln-Ann memories.17 He wasn’t talking about those of ex-New Salemites in general, although his argument makes it plain that “dim and misty” applies to a big chunk of that testimony as well. But it should be emphasized that Randall was referring specifically to Rutledge testimony, a fact that Wilson noted elsewhere.18 Thus Wilson suggested—unmistakably—that the Rutledges “kept the picture fresh” when it came to Lincoln and Ann. Wilson also argued that this picture suggests very strongly that Lincoln and Ann not only were in love, but were actually engaged to be married.

It must be acknowledged that Wilson’s comments about the retention of memory—via repeated reminiscence among family and friends over the years—point to something quite important. It gets to the heart of why Herndon’s inquiries are so valuable. Strewn throughout Herndon’s Informants are numerous vivid vignettes of life in New Salem and Springfield that, were it not for an oral tradition of conserving memories, would not have survived, greatly impoverishing our knowledge of the early Lincoln. And, in fact, one of the real gems of Lincoln testimony came from Robert B. Rutledge, Ann’s younger brother. There can be little doubt but that one reason Robert could summon up this testimony is that he had frequently told stories, and heard them, about Lincoln.

But with regard to Lincoln and Ann and romance, did the Rutledges keep the picture fresh?

Robert B. Rutledge served as the Rutledge family spokesman to Herndon on matters Lincoln. He consulted his mother, Mary, and his older brother, John M., before writing Herndon to report the family’s testimony. The consultation apparently yielded indirect testimony from another brother, David, who had died in 1842.19 In a follow-up letter Robert relayed to Herndon information he received from J. McGrady Rutledge (Ann’s first cousin). Herndon also exchanged letters with John M., and with Jasper Rutledge (another cousin). A Herndon investigator, G. U. Miles, interviewed Mrs. William Rutledge (Ann’s aunt by marriage and, due to an intermarriage, Ann’s first cousin as well). Very late in the game, in 1887, Herndon interviewed J. McGrady Rutledge.

None of the Rutledges—not one—offered a specific memory of Lincoln courting Ann. They all affirmed that a courtship took place, and with the exception of Mrs. William Rutledge, they all directly or indirectly affirmed that Lincoln and Ann were, in fact, engaged to be married.20 But none offered eyewitness images of them holding hands, exchanging tender glances, strolling through glades, or otherwise behaving like a couple in love. Thus from the outset one must wonder how the Rutledge family “kept the picture fresh.” There is no picture. The screen is blank!

Moreover, only three Rutledges claimed, or were said to have claimed, that they had personal knowledge of a romance. Jasper was born after Ann died, so in his case personal knowledge was not possible. But had a romance occurred, all of the others would presumably have had an “opportunity to know,” to use Wilson’s term, and therefore be able to claim to know. But the claims that were made, such as they are, came only from David (long since dead when Herndon was sniffing around), J. McGrady, and Mrs. William.

Wilson has asserted that Robert Rutledge learned about the romance and the engagement from Ann herself.21 If true, this would mean that Robert had personal knowledge of the romance. But if Ann ever once uttered the name “Abe” (or “Abraham” or “Lincoln”) to brother Robert, no trace of it is to be found in Herndon’s Informants, or anywhere else. Robert—the family spokesman—not only offered zero personal memories of lovebird action between Lincoln and Ann, he also did not report having had any conversation with Ann about it. This is easily verifiable. One simply needs to read the nine letters from Robert to Herndon in Herndon’s Informants. How Wilson got the notion that Ann discussed a romance with Robert is hard to fathom—particularly given the fact that Wilson co-edited Herndon’s Informants. This really is extremely puzzling.

What is there to the three Rutledges’ claims of personal knowledge of a romance?

The Rutledge Family Remembers (and Forgets)

Start with the deceased brother David, whose claim was reported secondhand by Robert. After Robert consulted his mother and brother, he wrote Herndon a long letter on or about November 1, 1866. It is here that he provided marvelously bright pictures of New Salem and Lincoln’s place in it: evocations of Lincoln laboring free of charge, addressing public audiences, telling jokes, performing acts of kindness, running for office, demonstrating strength, conducting himself honorably while acting as a second for a friend in a duel, wrestling, and other activities. Robert indicated that he personally witnessed at least some of these familiar Lincoln pastimes. He closed his letter, for example, with this: “I have seen him frequently take a barrel of whiskey by the chimes and lift it up to his face as if to drink out of the bung-hole. This feat he could accomplish with the greatest ease. I never saw him taste or drink a drop of any kind of spiritous liquors[.]”22 It is clear that Lincoln made quite a memorable impression on Robert Rutledge.

Fairly deep into the letter, Robert turned to the subject of Ann. He began with an account of Ann’s engagement to marry one John McNamar, a colorful sub-drama of Ann’s alleged relationship with Lincoln. McNamar was a prosperous New Salem merchant—and a friend of Lincoln’s—who had courted Ann, secured an engagement, and then went back East to tend to family matters. For a time he wrote Ann letters, then stopped. To all appearances he had left her in the lurch. Enter Lincoln, that well-known poacher of friends’ fiancées. According to Robert:

In the mean time Mr Lincoln paid his addresses to Ann, continued his visits and attentions regularly and those resulted in an engagement to marry, conditional to an honorable release from the contract with McNamar. There is no kind of doubt as to the existence of this engagement[.] David Rutledge urged Ann to consummate it, but she refused until such time as she could see McNamar—inform him of the change in her feelings, and seek an honorable release.

Mr Lincoln lived in the village, McNamar did not return and in August 1835 Ann sickened and died. The effect upon Mr Lincoln’s mind was terrible; he became plunged in despair, and many of his friends feared that reason would desert her throne. His extraordinary emotions were regarded as strong evidence of the existence of the tenderest relations between himself and the deceased.23

This is the totality of what Robert had to say to Herndon about Lincoln and Ann in this long and otherwise detail-packed letter. Note that the only cited witness is the dead David: no specific romance memories from Ann’s mother, none from brother John, and, as noted, none from Robert. Indeed, no specific memories from any living Rutledge. It’s peculiar, to say the least. If Lincoln had courted Ann during regular visits to the Rutledge home and eventually won her over, and if this had been a courtship conducted in the shadow of Ann’s missing fiancé, who, of all the living family members in 1866, would presumably have been most able to supply facts about this domestic drama? Ann’s mother, of course.24 An elder brother might also be supposed to have known something, not to mention Robert, who at the time of Ann’s death was seventeen. But instead of citing the living, Robert cited a brother who had died a whopping twenty-four years before Robert wrote to Herndon. The phrase “dim and misty” comes sharply to mind.

Note also that the only element of Robert’s romance account with any zing to it is the description of Lincoln’s reaction to Ann’s death: his “extraordinary emotions were regarded as strong evidence of the existence of the tenderest relations between himself and the deceased.” Regarded by whom as strong evidence? The record shows that Rutledge family recollections of Lincoln and Ann did not include personal knowledge of notable Lincoln grief. Nancy Rutledge Prewitt, Ann’s younger sister, told a newspaper correspondent in 1899:

It has been said that Mr. Lincoln was insane for a year after Annie’s death, with grief. I do not remember as to that… I have read that they did not dare to allow him to have a razor or knife at that time, but I never heard any of our family say so, and they were intimate friends with him as long as he was there. There are so many things in the papers that are not true.25

Indeed, in correspondence with Herndon shortly after the letter discussed above, Robert Rutledge twice specifically disavowed having witnessed Lincoln grief. The first disavowal: “[Do you] get the condition of Mr Lincoln’s mental Suffering and Condition [after Ann’s death]truthfully? I cannot answer this question from personal knowledge, but from what I have learned from others at the time, you are substantially correct.”26 The second disavowal: “I cannot say whether Mr Lincoln was radically a changed man, after the event [Ann’s death], of which you speak or not, as I saw little of him after the time…”27 In other words, Robert learned of Lincoln’s grief from hearsay. One scratches one’s head: If there had been romance, would not Lincoln have shared his grief with the family of the dead beloved?

A larger question arises. If, in a lengthy, thoughtful, detail-packed letter the contents of which were assembled and vetted by Rutledge family members, the family spokesman did not cite a specific memory of even one living family member about a love affair, but did cite events that no one in the family seems to have witnessed, and moreover characterized those events as “strong evidence of the tenderest relations” between Lincoln and Ann, what does this say about the Rutledges as witnesses of a romance? Why did Robert Rutledge’s account rely on memories of people outside of the family for “strong evidence”? It appears that Robert Rutledge’s most compelling evidence for a romance depended on a deductive leap from Lincoln’s grief.28 Yet he himself did not witness grief. One begins to suspect that the Rutledges did not, in fact, witness a romance.

Enter J. McGrady Rutledge, the second of the three Rutledges who claimed to have personal knowledge of a romance. In a letter dated November 21, 1866, written shortly after the letter just discussed, Robert informed Herndon that he had received a letter from J. McGrady, “a cousin about her [Ann’s] age & who was in her confidence.” Robert then quoted McGrady: “Ann told me once in coming from a Camp Meeting on Rock creek, that engagements made too far a hed sometimes failed, that one had failed, (meaning her engagement with McNamar) Ann gave me to understand, that as soon as certain studies were completed she and Lincoln would be married[.]”29 Apart from a statement by Mrs. William Rutledge, soon to be discussed, this is the first personal recollection that Herndon obtained from a living Rutledge about Lincoln and Ann. It’s also the last, except for a Herndon interview with McGrady many years later, in March, 1887. Herndon asked McGrady: “Do You know any thing Concerning the Courtship and Engagement of Abraham Lincoln and Ann Rutledge[.] If so state fully Concerning the same[.]” This is McGrady’s reply in full:

Well I had an Oppertunity to Know and I do Know the facts. Abraham Lincoln and Ann Rutledge were engaged to be married. He came down and was with her during her last sickness and burial. Lincoln was Studying Law at Springfield Ill. Ann Rutledge Concented to wait a year for their Marriage after their Engagement until Abraham Lincoln was Admitted to the bar. and Ann Rutledge died within the year.30

McGrady’s command of the facts here is shaky on one obvious count: Lincoln didn’t move to Springfield to pursue a career in law until 1837, well after Ann died. But the most striking thing about this testimony is, once again, the lack of concrete detail.

On to the third and final Rutledge who claimed personal knowledge of a romance, and to the small Rutledge-memory mystery mentioned earlier. In March, 1866, G. U. Miles, Herndon’s father-in-law and surrogate investigator, interviewed three former residents of New Salem: Mrs. Bowling Green, Mrs. William Rutledge, and Mrs. Parthena Hill. Mrs. Green told Miles that Lincoln was a “regular suitor” of Ann for two or three years before she died, and that Lincoln took her death “verry hard,” so much so that some observers thought he would “become impared.” Miles then turned to Mrs. William Rutledge:

Mrs Wm Rutledge who resides in Petersburg and did reside in the neighbourhood at the time of Said courtship and who is an Aunt to Said Ann Rutledge & acquainted with the parties & all the circumstances of the prolonged courtship coroberates all the above [Mrs. Green’s testimony.] Except She thinks that Ann if She had lived would have married McNamer or rather She thinks Ann liked him a little the best though McNamer had ben absent in Ohio for Near two years at the time of her death though they corrospanded by letter.31

“Would have married McNamer…”—this is hardly an endorsement of an Abe-Ann romance. There’s no mention of an engagement, either. It’s worth noting that Mrs. Green also qualified her comments on courtship: “She [Ann] had a nother Bow by the name of John McNamer who She thought as much of as She did of Lincoln to appearances[.]”32

Now, the mystery: Who exactly was Mrs. William Rutledge?

Herndon’s Informants identifies her first name as “Elizabeth,” and she’s described simply as “Ann’s aunt.” One of the nice things about Herndon’s Informants is that it contains a “Register of Informants” with succinct biographical profiles that include noteworthy relationships between the informants. Mrs. William Rutledge, however, does not appear in the register. It is very unlikely that this was a deliberate exclusion. However, for reasons soon to be seen, it is a bit eerie.

Mrs. William was the wife of the brother of Ann’s father, James Rutledge. Primary-source evidence shows that, in fact, she actually was named Susannah Cameron Rutledge.33 By virtue of the fact that her mother and Ann’s mother were sisters, Susannah was Ann’s—and Robert Rutledge’s—first cousin as well as aunt by marriage.34 None of this signifies much, except that it raises the question of why Robert apparently did not include Susannah in his family consultations, for she clearly had known Ann very well all of Ann’s life.

What is significant: Susannah Cameron Rutledge was the mother of J. McGrady Rutledge.35 This fact is nowhere mentioned in Herndon’s Informants.

It will be recalled that Susannah and J. McGrady were the only living Rutledges who told Herndon that they had personal knowledge of Ann’s relationship with Lincoln. Yet this mother-son duo had very different things to say about that relationship. J. McGrady affirmed, albeit with remarkable terseness, that Ann and Lincoln were engaged to be married. Susannah thought that Ann, had she lived, would have married McNamar. This in a nutshell is the grand total of what Herndon got from the two living Rutledges who actually “claimed to know.”

Did J. McGrady and his mother discuss or perhaps even argue about which one of them had the correct version of Lincoln and Ann? This will almost certainly never be known. But one thing is very clear indeed: J. McGrady and Susannah Rutledge did not keep “the picture fresh by frequently having it recalled to” them. Neither did their kinfolk. The only “pictures” the Rutledge family gave Herndon about Lincoln and Ann—David’s, J. McGrady’s, and Susannah’s—surely cannot be characterized as “fresh.” From what Herndon has passed down to us in Herndon’s Informants, it is hard to imagine that the Rutledge family—prior to Herndon’s Rutledge lecture, which made the legend a nationally famous melodrama—sat around fireplaces late into the night recalling to each other the nuances of Lincoln’s love for Ann.

Conclusion

The foregoing addresses only a portion of the case made by legend revivalists for the Ann-Lincoln romance and engagement. Douglas L. Wilson, John E. Walsh, and others also cite the testimony of many non-Rutledge New Salem residents who either knew both parties or had heard about them. Suffice it to say that, under close scrutiny, the non-Rutledge testimony stands up little better than does the Rutledge testimony. David Donald, after noting that 1998’s Herndon’s Informants “has made it possible more easily and systematically to examine all the testimony that Herndon collected” on the legend, writes in his new book, “We Are Lincoln Men”:

Looked at anew, it [the testimony]is impressive for its contradictions. Members of the Rutledge family were certain that there had been a firm engagement between Lincoln and their sister; Mrs. Abell, who may have been Lincoln’s closest confidant in New Salem, professed to know nothing about a love affair, though she testified to Lincoln’s genuine grief at Ann’s death.36

Donald is tactful in the pages he devotes to explaining why he no longer accepts the legend. But it’s clear that he is backing away from a major embarrassment. Nearly sixty years after J. G. Randall delivered a seeming coup de grâce to the Ann Rutledge legend, the legend’s revival may be nearing its own sudden death. This raises two final questions. How did Douglas L. Wilson and other hard-core legend revivalists persuade themselves that there is “overwhelming evidence” for an Abe-Ann romance? And why did the Lincoln establishment—composed as it largely is of very smart people—so credulously swallow the revival when the evidence behind it can so easily be shown to be far from “overwhelming”?

Perhaps it would require a cultural anthropologist to explain the curious ways of the Lincoln tribe. Or perhaps an expert on collective hallucination. The only explanation I can think of is that even smart people, when confronted with an argument they want to believe, will sometimes believe the argument despite poor evidence.37 Well, then. Why would the Lincoln establishment want to believe the Rutledge legend? Perhaps because it sexes up the Lincoln story and sells books. Perhaps because Lincolnists feel a need to find evidence that Lincoln was sexually attracted to women, which is absent in reliable accounts of his life until he married at the age of 33.38 If, as seems to be the case, these reasons or variants of them do in fact help to explain how the Ann Rutledge legend re-hornswoggled Lincoln country, there is only one word that fits the situation. This is a scandal.

Notes

1. Paul M. Angle delivered the first thorough scholarly debunking of the Rutledge legend with “Lincoln’s First Love?”, Bulletin No. 9, Lincoln Centennial Association, Dec. 1, 1927.

2. J. G. Randall, “Sifting the Ann Rutledge Evidence,” appendix to Lincoln the President: Springfield to Gettysburg, Vol. 2, pp. 321-342. (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1945.)

3. Two highly influential articles appeared in 1990 that set the stage for the Rutledge-legend revival: John Y. Simon’s “Abraham Lincoln and Ann Rutledge,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, II, 1990, and Douglas L. Wilson’s “Abraham Lincoln, Ann Rutledge, and the Evidence of Herndon’s Informants,” originally in Civil War History, 36, Dec., 1990, reprinted in Lincoln Before Washington: New Perspectives on the Illinois Years (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1997).

4. In Lincoln Before Washington alone, Wilson used the word “overwhelming” or “overwhelmingly” five times to describe the pro-legend evidence he discerned, on pages 83, 88, 89, 137, and even in the index on page 189, under “Rutledge, Ann”: “informant’s [sic]agreement about love affair with AL overwhelming, 83[.]”

5. The Library of Congress made the Herndon-Weik Collection available to scholars in 1945.

6. Dr. Tripp died peacefully at home in Nyack, New York, May 17, 2003, a scant two weeks after putting the finishing touches on the Lincoln ms.

7. William A. Percy, a mutual friend who has contributed to the G&LR, introduced me to Dr. Tripp.

8. Herndon’s Isaac Cogdal interview was dated 1865-66, thus the ambiguity as to whether four or five years had elapsed.

9. David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), p. 58.

10. David Herbert Donald, “We Are Lincoln Men”: Abraham Lincoln and His Friends (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), pp. 23, 224. C. A. Tripp, “The Strange Case of Isaac Cogdal,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 23, Winter, 2002, pp. 69-77.

11. Wilson, Lincoln Before Washington, p. 88.

12. Herndon launched the Rutledge legend with a lecture delivered at Springfield, Ill., November 16, 1866: “Abraham Lincoln, Miss Ann Rutledge, New Salem, Pioneering, & the Poem.” Courtesy of Dr. Thomas F. Schwartz and the Illinois State Historical Society, Dr. Tripp obtained a photostat of the lecture’s original broadsheet (the entire text of the lecture), which Herndon printed and distributed. The broadsheet was what made a sensation in newspapers and journals; the audience of the lecture itself was not large.

13. Douglas L. Wilson and Rodney O. Davis, eds., Herndon’s Informants: Letters, Interviews, and Statements about Abraham Lincoln (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1998. Hereafter cited as HI.

14. Scholarly interest in the “inner” Lincoln has soared in recent years, which in part accounts for the rehabilitation of Lincoln reminiscence: without anecdotal evidence it’s hard to get very far on the subject of Lincoln’s personality.

15. Wilson, Lincoln Before Washington, p. 31.

16. Ibid., p. 33. In a highly informative review essay on Wilson’s work, “Telling Lincoln’s Story,” dated 12/10/98 in manuscript form, Dr. Richard S. Taylor of the Illinois State Preservation Agency on page 14 quotes Wilson: “Aunt Louisa’s ‘experience,’ says Wilson, seems to have been like that of ‘most.’ Well, if that is true, ‘most’ old settlers may have gotten it wrong, since it is now believed that she mislocated several buildings and part of the road.” Taylor’s essay courtesy of Thomas F. Schwartz.

17. Randall, “Sifting the Ann Rutledge Evidence,” p. 330.

18. Wilson, Lincoln Before Washington, p. 86.

19. The date of David’s death is significant for reasons to be seen. James Rutledge Saunders, compiler, “The Rutledge Family of New Salem, Illinois,” p. 2. Photocopy of the original courtesy of Thomas F. Schwartz.

20. Since Robert did not quote his mother, Mary, or his brother, John M., we cannot know with certainty that either one actually affirmed an engagement, or indeed whether either had anything at all to say about a romance. However, Robert told Herndon that he would have to consult both Mary and John to give an accurate account. If Mary or John had not affirmed an engagement, presumably Robert would have reported it to Herndon. Thus one assumes that they backed the engagement story. However, in his three letters to Herndon, John did not mention an Ann romance with or engagement to Lincoln. He also did not mention

Lewis Gannett, a freelance writer based in Boston, is a literary editor of this journal.