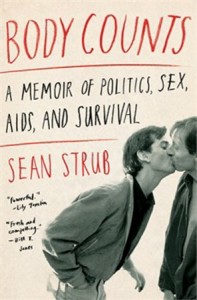

Body Counts: A Memoir of Politics,

Body Counts: A Memoir of Politics,

Sex, AIDS, and Survival

by Sean Strub

Scribner. 420 pages, $30.

IN 1976, at age seventeen, Sean Strub got a job operating an elevator on the Senate side of the U.S. Capitol. He scarcely believed his luck. What could be better than daily contact with the most distinguished statesmen in the country? “There wasn’t much room in my elevator, but I loved how large the world became for me within its walls.”

Other boys went girl-crazy; Strub found his passion in politics. Soon enough he learned that it didn’t have to be chaste. Washington was a very gay town. Passengers in the elevator included men who spoke a certain way, dressed with particular flair. Strub noticed them, and they noticed him. He discovered the existence of a sexual subculture that communicated with secret codes, a demimonde at play in niche restaurants and bars. A bright and ambitious young man could make friends in that kind of environment. Strub forged alliances useful for a public-service career. But there was a problem. His sexual side had to remain hidden.

This memoir reminds us how taboo it was back then to be gay. Paradoxically, however, gay men ran some of the country’s sharpest political organizations. Why did they choose a profession that could ruin them? Strub’s motivation, which applied to a number of notable gays in politics—Bayard Rustin, Allard Lowenstein, Gerry Studds, and Barney Frank come to mind—perhaps can be summed up with one word: idealism. It was a way to serve the country. Strub doesn’t theorize about connections between homosexuality and working for the public good, maybe because it’s a question for the sociobiologists. He does discuss the irony that he entered secret service, so to speak, on the eve of gay liberation’s national eruption.

He had heard of Harvey Milk, a San Francisco city supervisor and one of first openly gay elected officials in the U.S. When a deranged colleague murdered Milk in November 1978, most media covered it with an “only in San Francisco” angle. Washington’s scruffy gay press saw it differently, as the martyrdom of a new kind of hero. Strub started to think about the viability of gay politics. In October of the following year, massive numbers of lesbians and gay men converged on D.C. for the first national gay rights march. It was a festive event, huge, confident, inescapable. By this time Strub was leading two very busy lives, one closeted, the other devoted to electioneering. They didn’t intersect publicly because he wanted to make his mark in big-time politics, where homosexuality remained anathema. He had gay friends in the same predicament. Most of them didn’t dwell on it and tended to make themselves scarce when he brought up sexual liberation. It didn’t seem to Strub that he could combine the two sides of his life.

AIDS intervened. The decade preceding the plague had seen a rapid expansion of gay entertainment culture. Liberation meant a party, and why not? Homophobia still ruled the land, but that provided all the more reason to flaunt newfound self-confidence. For the first time gays celebrated themselves as belles of the ball. Strub notes that it helped to dispel a sense of woundedness that many gay men, including him, had harbored since their bullied boyhoods. Erstwhile wimps suddenly ruled a new world, from the dance floor no less. Strub found the D.C. political closet increasingly restrictive. He moved to New York, where doormen at Studio 54 waved him in. And then, kaboom! AIDS crashed into gay life like a giant asteroid—like an extinction-level event.

Surprisingly little history has been written about the community’s response to the early plague years. Of course, everybody knows that it was a harrowing time. Or maybe not; how many are old enough to remember wraith-like men with purplish skin barely able to hobble down the sidewalk? Strub tells his stories calmly, and he deploys a gentle sense of humor. At first this comes across as a polite effort to help the reader through the rough spots. Then you realize he’s describing experiences so horrifying that just the facts will do. Here’s an example: A friend of Strub’s collected exotic curiosities, mummy fragments, taxidermy, and the like. This man’s lover was desperately ill; patches of his body had turned “nearly black with thick, waxy, foul-smelling lesions and dead skin.” One day they were preparing to leave for the hospital. In the bed they found “a piece of dark organic matter about the size of a flattened walnut.” Apparently the lover had molted a lesion. Strub’s friend took it to the hospital for the doctor’s inspection. Later, back home, “he looked up at the stuffed deer head hanging on the wall above their bed and saw that it was missing its nose.”

Strub covers a lot of highly personal ground in Body Counts. Gay men his age lost staggering numbers of friends, on a scale otherwise known only to wartime soldiers. It was the kind of loss that soldiers famously find hard to discuss; maybe this is a reason that relatively few AIDS memoirs have been published so far. But AIDS wasn’t, of course, just a personal ordeal. I recall a widespread fear in the 1980s that authorities would put gays in concentration camps. Strub didn’t feel that degree of panic, but very early on, before AIDS had even been named, he worried about the fate of gay liberation. If the disease became known as a buttfuck curse, would hopes for acceptance vanish?

That fear turned out to be naïve. But does it tell us something? I think so. It was only on reading Strub that I understood how fragile and experimental gay legitimacy was 35 years ago. The grand fanfare of the 1970s hadn’t really been all that successful. To put it another way, if gay pride had been secure by 1980—if it had reflected a genuine self-confidence—then AIDS wouldn’t have so easily called up visions of banishment, of liberation tumbling down.

The crisis led to what came next, namely, gay fury and organization. AIDS decimated the community, and the community, much to everyone’s surprise, got up and fought back. This chapter of AIDS history, of Larry Kramer and ACT UP, is the most familiar. By 1987 Strub had established a successful direct-mail business that raised money for nonprofit corporations. ACT UP recruited him to lead its fundraising efforts. Pushing thirty, he felt a little “old” compared to many of the organization’s activists. Also, he still entertained ambitions to run for office. But he had a pressing personal reason to join: he’d been showing AIDS symptoms for some time, and was starting to get sick. Strub had found a way to fuse his private life with a public-service calling. He pursued it with impressive determination, founding POZ magazine in 1994 [the same year in which this magazine began], a glossy periodical for people living with HIV. Today he runs the Sero Project, which combats AIDS stigma and criminalization.

Body Counts contains a number of celebrity cameos, including Tennessee Williams, Gore Vidal, and Yoko Ono. It also includes some very interesting photographs. The Vidal anecdote is especially fun, an instance of Strub’s amusing deadpan humor. This book is downright uplifting; reading it will do you good.

Lewis Gannett, an associate editor of this magazine, has contributed several articles on Abraham Lincoln’s same-sex relationships.