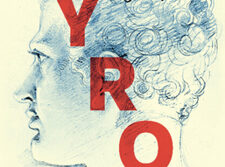

FROM ABOUT 1935 until his death in 1989, the Greek artist Yannis Tsarouchis painted and openly exhibited more studies of men in uniform and more male nudes than any artist outside what might now be called the world of erotica. He was a rough contemporary of two great artists of the male figure, Paul Cadmus, who didn’t paint genitals, and Tom of Finland, who painted little else. Tsarouchis’s unapologetic manner in presenting these nudes long predated that of David Hockney, who would come to admire him. In Greece Tsarouchis’s name is a household word, but outside his country he and his work have been little known except in some European art circles and certain gay ones. Also little known is that a large body of his work is accessible in one of the most charming ways for art to be displayed—in the artist’s former home, now a museum.

That body of work is of Greek subjects. Country village men wear their one good city suit awkwardly. Young men sit bored in tavernas, while others dance. Soldiers and sailors sit uncomfortably in their required uniforms as if they long to get rid of them—and do, lounging barefoot on flowered 19th-century couches, lying nude on the brass beds of cheap hotels. While these bodies seem earthy and are even made available to us as viewers, other male figures are more ethereal, a perfect desired form made light with the addition of the traditional—if improbable—wings of an Eros.

Tsarouchis used techniques from artists of the Greek tradition for his first audience, his countrymen, to remind them that the glory of Greek art had not faded. It did not end when Rome conquered Greece.