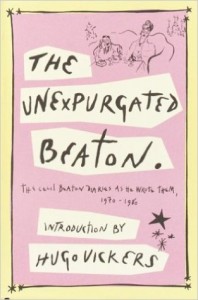

The Unexpurgated Beaton: The Cecil Beaton

The Unexpurgated Beaton: The Cecil Beaton

Diaries as He Wrote Them, 1970-1980

Introduction by Hugo Vickers

Alfred A. Knopf. 489 pages, $35.

Cecil Beaton was many things: photographer, writer, artist, designer. His stage sets and costumes won him two Academy Awards. He was also an incorrigible talker and an arbiter of style. As a personality and artist, he was in demand all over the world as a companion; and many, including the Queen Mother, referred to him as “the best company.” His charmed but disciplined life included his job as the official photographer to the royal family of England, a title that he abhorred.

Beaton’s international access was the perfect foundation for a 145-volume diary that he kept in longhand in exercise books or in outrageously expensive marbled books from Venice. His diaries began in 1922 and were clearly not intended for a reading audience. In 1932, for instance, he wrote: “If I knew anyone had read this I’d almost go mad and yet I feel I have to write it. It’s so much myself—the real self that not a single person alive knows.” Later, he added: “I don’t want people to know me as I really am but as I’m trying to be.”

While letting his opinions rip when discussing famous friends and acquaintances of his time, Beaton was discreet to a fault when discussing his private love life. In fact, there’s nothing overtly sexual in the diaries. The one affair he did record is so Victorian in its description that one thinks of the tiny skirts arranged around chair legs in that era. The closest he ever got to the penis was his fearful entry about prostate surgery in 1971: “Due to the female hormones I have to take daily, my breasts have enlarged and the nipples are quite painfully delicate. I don’t mind this much, as I have no desire left. I have had three unexpected wet dreams but I have no lascivious thoughts and to add to my feeling of éloignement I am utterly mortified that my cock has shriveled.”

When it came to famous people, however, Cecil held nothing back. This volume of unexpurgated entries begins in 1969 with a scathing entry on Katherine Hepburn, whom Beaton calls “the egomaniac of all time”:

That beautiful bone structure of cheekbone, nose and chin goes for nothing in its surrounding flesh of the New England shopkeeper. Her skin is revolting and since she does not apply enough make-up even from the front she appears pockmarked. In life her appearance is appalling, a raddled, rash-ridden, freckled, burnt, mottled, bleached and wizened piece of decaying matter. It is unbelievable, incredible that she can still be exhibited in public.

Of all the famous people that Beaton wrote about, Hepburn received his most extreme wrath. He found her lacking in feminine grace and manners and accused her of being miserly and a bully.

Other celebrities fare better but there are still plenty of wasp-like stings. Mae West’s apartment in Hollywood, for instance, had “dust covering everything not on view”: “In a nearby toilet a discarded massage table was caked with gray, and when I put my finger on it, I discovered the dark red artificial leather beneath. Everything was grimy. The rushing on the lamps quite black with grime.” West herself was, according to Beaton, rigged up in the highest possible fantasy of taste. She could hardly be considered human. The costume of black with white fur was designed to camouflage every silhouette except the armour that constricted her waist and contained her bust. The neck, cheeks and shoulders, were hidden beneath a peroxide wig. The muzzle, which was about all one could see of the face, with the pretty capped teeth, was like that of a nice little ape.

In those days actor Tom Selleck was one of Mae West’s bodyguards, and Beaton describes him as a “beautiful, young, spare, clean, honest specimen of US manhood.” That’s all he says about Selleck.

Beaton called Virginia Woolf’s refusal to pose for him “swinish,” and added that the famous writer was, in many ways, a swine. Coco Chanel was no beauty, he opined, but by her allure “she put all other women in the shade.” He loved the fashions of Yves St. Laurent, calling them “remarkable,” noting how he “has gone his own way and created something without any mind to the public’s reaction.”

Rose Kennedy, he wrote, was “publicity mad” and an “old toughie.” Leonard Bernstein he found “disgusting and repellent and too much the charlatan show off.” Salvador Dalí had “appalling bad breath” which made it impossible to regard the things the artist wanted to show him in close quarters. Queen Elizabeth, he observed after receiving his knighthood, “wore low sensible shoes … she’d make an extremely good hospital nurse or nanny.” And Marlene Dietrich he described as Jean Cocteau’s “sacred monster in person.”

The diaries contain some anti-Jewish slurs. For example, while photographing Nureyev in London, he wrote about an editor of Vogue: “[Nureyev] gave me a look of boredom at the way the Jewess Vogue Editor carried on. He rolled his eyes in disgust at some satin outfit costing many hundreds of pounds.” Earlier references to Leonard Bernstein “tossing his gray Jewish locks” conjure up curious images.

Next to Hepburn, Beaton reserved his greatest contempt for Liz Taylor. “I have always loathed the Burtons for their vulgarity, commonness and crass bad taste, she combining the worst of US and English taste, he as butch and coarse as only a Welshman can be,” he wrote. Taylor got his writing hand into a special fury:

Her breasts, hanging and huge, were like those of a peasant woman suckling her young in Peru. They were seen in their full shape, blotched and mauve, plum. Round her neck was a velvet ribbon with the biggest diamond in the world pinned on it. On her fat, coarse hands more of the biggest diamonds and emeralds, her head a ridiculous mass of diamond necklaces sewn together, a snood of blue and black pompons and black osprey aigrettes.

Between exciting excursions to Venice, Paris, and London, as well as photo sessions with the Queen Mother, Beaton was very much aware of his aging body and the effect this was having on his general mood. Old age, he wrote, meant suffering one indignation after another. “I woke up to find I had a low comedian’s red nose. With age, all sorts of awful things appear. My forehead, chest, and shoulders have broken out in huge freckled spots, and one toad-like mark appears under one eye with very bad results.” Obsessed with the ravages of age on himself and his friends, he recorded every set of false teeth, every enlarged mouth, every shrunken body among old friends who were once beautiful. When he caught a glimpse of himself in the mirror he saw his stomach “bulging out of a tight pair of trousers, my hormone’s breasts enlarged with full nipples—God, what a creature!” But the next day he combs his few strips of wispy head hair and begins the social whirl all over again.

Thom Nickels, a Philadelphia-based writer, journalist, and poet, is the author of Tropic of Libra, a novel.