Polaroids: Mapplethorpe

At the Whitney Museum, New York, in collaboration with the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

May 3 through Sept. 7, 2008

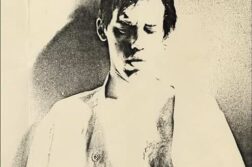

ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE’S Polaroid photographs are not a well-known part of his œuvre, but they contain virtually all of the basic themes and elements that blossomed and matured in his later work. Beginning in 1970 and for roughly five years when he was in his twenties, Mapplethorpe created a body of work that runs to roughly 1,500 Polaroid photos. The Whitney Museum of American Art in New York recently mounted an exhibit of about a hundred of these pictures entitled “Polaroids: Mapplethorpe” in its Sondra Gilman Gallery. The exhibit was curated by Sylvia Wolf, recently named Director of the Henry Art Gallery in Seattle, Washington, in collaboration with the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation in New York.