West Side Story

Directed by Arthur Laurents

Palace Theatre, New York

IN THE 1950’s, four gay men of genius got together and created what is arguably the greatest Broadway show ever. The brainchild of choreographer Jerome Robbins, West Side Story was  initially going to be called “East Side Story” and focus on Jewish–Catholic tensions. But once the more dramatic gang war idea took hold, pitting white Americans against Puerto Ricans on rough turf on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, the team’s imagination was fired up. West Side Story was Stephen Sondheim’s first Broadway show as a lyricist and Leonard Bernstein’s fourth Broadway score (after On the Town, Wonderful Town, and the Broadway operetta Candide). Arthur Laurents, later famous for Gypsy, wrote the book.

initially going to be called “East Side Story” and focus on Jewish–Catholic tensions. But once the more dramatic gang war idea took hold, pitting white Americans against Puerto Ricans on rough turf on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, the team’s imagination was fired up. West Side Story was Stephen Sondheim’s first Broadway show as a lyricist and Leonard Bernstein’s fourth Broadway score (after On the Town, Wonderful Town, and the Broadway operetta Candide). Arthur Laurents, later famous for Gypsy, wrote the book.

West Side Story was a groundbreaking musical tragedy with two corpses on stage at the end of Act I. The dance-driven vehicle featured a stunning score with operatic and symphonic sophistication, an eclectic mix of memorable tunes unified through the use of the “tritone”—an interval of three dissonant whole notes that produced a feeling of tension or dread (you can hear it clearly at the beginning of “Maria”). The ever-resourceful Bernstein even included a jazzy 12-tone fugue in his number, “Cool.”

The show opened in 1957 and had a successful run of 732 performances. However, it lost the Tony for Best Musical to the more upbeat The Music Man. In 1961, a movie version starring Natalie Wood was released, nabbing ten Oscars. The LP of the movie soundtrack sold like hotcakes.

The Broadway revival of West Side Story that opened at the Palace Theatre earlier this year was supposed to arrive in time for the show’s fiftieth anniversary at the end of 2007, but didn’t quite make it. Yet it was worth the wait. Nonagenarian Arthur Laurents, coming off of a successful revival of Gypsy with Patty Lufone, directed this revival and threw in a few new twists. For the sake of realism and to heighten racial tensions, for example, some dialogue and two numbers—“I Feel Pretty” and “A Boy Like That / I Have a Love”—are performed in Spanish without translation. In interviews, Laurents had promised a more violent, sexier production, but there’s really no more blood, flesh, or tears than what you see in the movie. As director, Laurents does a capable job but adds nothing all that novel or dynamic.

But perhaps Laurents’ fidelity to the original is just as well: the work was already done by Bernstein and Robbins. The stunning music and dance only need to be executed competently, and then you have a show that flies—and this one does for the most part. Jerome Robbins’ protégé, Joey McKneely, did a meticulous job reproducing Robbins’ jazzy and balletic steps; and, unlike recent revivals of Sondheim musicals in which the original orchestration has been drastically scaled down, this West Side Story features a full Broadway orchestra with all the special percussion that Bernstein called for, conducted by Patrick Vaccariello.

The excitement begins with the iconic opening chords as the Puerto Rican gang, the Sharks, and the white gang, the Jets, face off in an Upper West Side lot between the fire escapes and tenement façades. For an uneducated, pugnacious bunch, they sure know how to dance up a storm with style. I just wish the stage had been a bit wider and deeper, but this constriction perhaps added to the mounting claustrophobia. For “The Rumble,” where everything goes wrong, the highway looms dynamically overhead as a big fence comes down like a curtain, or rather, a cage—the only time when the set snaps into action, a welcome change. Tony, who is supposed to stop the violence, gets caught up in it after his best friend Riff is stabbed by Bernardo, Maria’s brother. He retaliates by killing Bernardo, and all hell breaks loose. Maria loses her innocence, and her touching monologue at the end over the dead body of her lover still elicits tears.

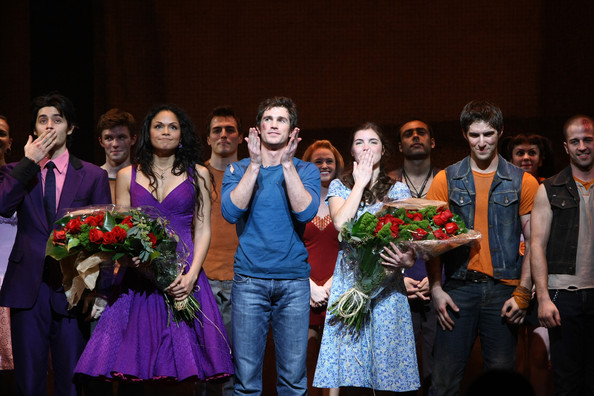

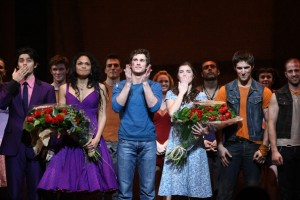

Bernstein’s masterpiece is a notoriously difficult show to cast—everyone in it seems to need both Metropolitan Opera and New York City Ballet credentials! I wish Matt Cavenaugh, who can certainly hit the high notes in “Maria,” were a bit more quirky and charismatic—he’s simply too much of a pretty, all-American boy. Similarly, George Akram’s Bernardo doesn’t register as strongly as Cody Green’s riveting Riff. The standouts in the show were Argentinean Josefina Scaglione and Karen Olivo (who starred in the Latino-fueled hit, “In the Heights”). And the ensemble work was excellent.

Given that all four of the original show’s creators—Bernstein, Robbins, Laurents, and Sondheim—were gay, West Side Story is remarkable for its unqualified heterosexuality and the near absence of sexual ambiguity in its characters. This tradition is maintained in the new production by Laurents, who had written the gay killer characters in Hitchcock’s Rope but shows no inclination to “gay up” this revival for contemporary audiences. This production is so straight that it doesn’t even allow for the subtextual readings that the movie version permitted. After all, who are these guys who dance in the streets with colored sneakers? Are Bernardo and Riff, who’d rather spend time with the boys than with their girlfriends, secretly attracted to each other? Laurents could certainly have explored these questions if he’d wanted to; what we have is a fine revival that does justice to the original play’s tale of social, if not sexual, rebellion.

Robert Hilferty passed away in late July, while this issue was still current. He was a New York-based writer and filmmaker who was completing a film called Babbitt: Portrait of a Serial Composer.