FASHION has been called a communal art. Fashion of all kinds—clothing, jewelry, furniture, even architecture—can signal status in a social group and can be used to show off wealth. It can promote individuality, as in haute couture, or social homogeneity, as in teen clothing fads. The term is also often used as a synonym for glamour, beauty, and style. Couture, however, took a distinct “downtown” turn in the 1980’s with the emergence of Stephen Sprouse, who set the fashion world on fire as the first designer to successfully merge street culture, punk, and high fashion in edgy clothing designs incorporating graffiti, vibrant and at times even garish colors, plus a fine arts sensibility. By the time Sprouse died of heart failure at age fifty in 2004 (following a diagnosis of lung cancer the previous year), he had produced a body of work considered by many to be the most visionary of his time.

Sprouse’s career, designs, and influence are explored and celebrated in The Stephen Sprouse Book, by brothers Roger and Mauricio Padilha, recently released by Rizzoli. And a fine book it is, by two individuals who know their subject well. With backgrounds in fashion and public relations, the two Padilhas co-founded MAO Public Relations along with MAO SPACE, a series of runway shows that coincide with New York Fashion Week each year. They also co-edit MAO MAG, a popular semi-

annual fashion publication. Fans of Sprouse’s work for many years, they wrote their book with full access to the designer’s archives. When I interviewed Roger Padilha for this article, he confided that Sprouse’s work as been a lifelong fascination: “Mauricio and I were just huge fans of Stephen’s work from a very early age. It combined everything we loved—Warhol, Blondie, punk, color, nightlife, space age, etc. When we first saw his clothing on TV, we had to go out and buy it.”

Stephen Sprouse was born on September 12, 1953, in Dayton, Ohio, and from an early age was something of a fashion design prodigy. Lucky child that he was, he had his parents’ full support in his artistic proclivities. Through family connections, his father helped him to secure a summer internship with Bill Blass when Stephen was only fourteen. By age nineteen he was working full time with Halston, and a few years after that he moved out on his own to start making his personal imprint on the design world.

Like many fashion designers, Sprouse was gay. But neither his private life nor the ins and outs of his career are the focus of the Padilha brothers’ large-format volume. Instead, its 256 color-drenched pages submerge the reader in the creations of a visual imagination that clearly reveled in the human body and how it can be draped, bespangled, and shown off in an almost endless variety of fabrics, ornamentation, and poses. Here is Roger Padilha’s description of Sprouse’s first runway show in Spring 1984 in the book’s introductory essay:

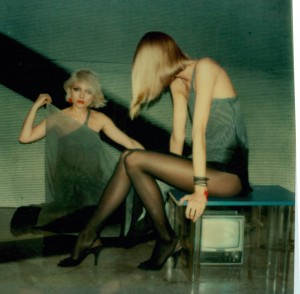

The show began with models clad entirely in black, then led to outfits in contrasting Day-Glo colors that caused the normally staid fashion audience to erupt in an ebullient cheer. Evening wear consisted of silk micro-minis with words such as “ROCK” and “LOVE” boldly spray painted across the models’ bodies and then covered with clear sequins. Stephen had designed every aspect of the collection, from the head wear … to the specially made “motorcycle” boots … to the sterling silver alphabet pins … mimicking his graffiti. … Also notable were the wrap skirts for men designed to be worn over trousers.

But it wasn’t just fashion audiences that went wild over Sprouse’s designs. It was also the larger downtown culture emerging at the time in New York’s East Village, where Sprouse sometimes lived and often clubbed with friends, notably photographer–illustrator Steven Meisel and transgender model Teri Toye. He dressed his close friend, novelist Tama Janowitz (Slaves of New York, 1986), and created the onstage look for another close friend, Debbie Harry, the lead singer of Blondie. He also dressed male celebrities such as Andy Warhol, Mick Jagger, Chris Stein (also of Blondie), Iggy Pop, Billy Idol, and the members of the band Duran Duran, among others.

As a popular fashion designer and a gay man, Sprouse worked and socialized largely in gay circles. Clad all in black (including black nail polish) and sporting a black wig, his handsome face with its dimpled chin was a familiar fixture in New York’s downtown clubs and gay bars. When I asked Roger Padilha for comments on the book and asked why virtually nothing of Sprouse’s gay life is mentioned in its pages, he answered:

We purposely left out Stephen’s personal life aside from the relevant childhood stories that led up to his becoming an artist. Stephen was a very private person, and that was one reason. But the main reason was that the book is about his art, and while some artists create work that is informed by their personal lives, we didn’t feel this to be the case with Stephen. His work was based on his fantasies and not really on what was going on in his life. That said, he was gay and had many different relationships throughout his time, and by all accounts led a very full, rich social life.

Sprouse’s designs may not have been based on what was occurring in his personal life, but his work nevertheless intersected the gay world, and his experience as a gay man, in a number of ways. Certainly his status as an outsider who was violating social norms to have sexual relationships with other men must have contributed to his willingness to break traditional molds in his fashion designs. Then there were his friendships with gay artists such as Andy Warhol and Keith Haring, both of whom were breaking quite a few rules in the creation of their work. The influences there remain to be determined.

There are also hints of a queer political consciousness. For example, the book quotes transgender model Teri Toye on the presentation of Sprouse’s Spring 1984 collection at the Ritz nightclub in New York’s East Village: “Many of the looks were androgynous and we knew that having boys in skirts and a transgendered fashion model [Teri Toye herself] as the star of the show might be considered scandalous, but it was really all about the æsthetic and attitude. And perhaps a little in the back of our minds, we wanted to do that because we felt it was important to move society forward.”

One further intersection, this time with gay history, should be noted: in September 1987, Sprouse and his financial backers opened the Stephen Sprouse Store at 99 Wooster Street in New York’s SoHo section, devoted to selling clothing and accessories designed by Sprouse. The Stephen Sprouse Book notes that the 5,600-square-foot tri-level space was a former firehouse. What it fails to mention is that in the early 1970’s New York’s Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) had used the same space to run a “danceteria,” an early effort by the organized gay community to wrest control of gay public spaces from the mafia, which controlled both bars and dance clubs. But was Sprouse himself aware of this? Two years earlier when he moved his design studio to 860 Broadway, he was certainly aware that the space was a former site of Andy Warhol’s Factory.

In 1984, the Council of Fashion Designers of America gave Sprouse its Best New Designer Award, the fashion world’s equivalent of an Oscar. But despite this recognition, and despite the popularity of his work with the downtown crowd both gay and straight, he had little commercial success for many years. The stores he opened (including the one at 99 Wooster) were short-lived, and his company had to declare bankruptcy. Then, in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, he was brought on board by labels and retailers like Louis Vuitton, Diesel, and Target, and his designs finally hit a mainstream nerve. He was on a roll, with many other projects in the offing, when his untimely death in 2004 brought a halt to everything.

Or did it? According to Roger Padilha: “We see Stephen’s work in so many different media outside of fashion. The most memorable are the iPod campaigns with silhouettes and neon backdrops—those are so Sprouse! And of course his graffiti is reappropriated for advertisements all the time.”

There are also the Sprouse fans who continue to treasure and wear the clothes he designed. The book quotes Debbie Harry, who’s often known as “Blondie” because of her role in the group: “I still have his stuff. I guard it with my life.” It also quotes Paige Powell, Warhol insider and former assistant publisher of Warhol’s Interview magazine: “At one point I was going to donate some of my Stephen Sprouse clothes to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I called Harold Koda and he said he would be interested in taking some of them when I was finished wearing them, but then I thought, ‘I’m still wearing them.’ They are so timeless and still look as amazing today as they did twenty years ago.”

Another Sprouse legacy is the fine art he produced over the years. According to Roger Padilha: “I think his art and his fashion designs were one and the same. At the beginning of his career, Stephen would make canvases, then make clothes to photograph in front of the canvases. So the fashion and fine art were really processes that went hand in hand. It just so happened that his fashion work took off first. I do think, however, he was leaning more toward fine art and less toward fashion by the end of his life.”

Perhaps Sprouse’s most notorious fine art image was of Iggy Pop crucified. The book quotes supermodel Kate Moss: “One night, he phoned up and said, ‘I’ve got a present for you. Can I drop it over?’ And he came over with an ‘Iggy on the Cross’ painting. It was fantastic. I lined the painting in black lights so it would glow and my neighbors from across the street started complaining that it was blasphemous. I was like, ‘Whatever.’ And I just kept the curtains drawn from then on.”

It’s clear from the paintings reproduced in the book—which includes images not only of Iggy Pop but also of Sid Vicious, unnamed “Rock Boys,” “Hardcore Boys,” “Guitar Boys,” skinheads, and even electronic amps—that, like Andy Warhol, Sprouse was obsessed with the hard rock music world. Equally obvious is that his art was heavily influenced by the Pop Art movement, although his images went Warhol one better in the intensity of their Day-Glo colors. It’s hard to know where he would have gone with his art had he lived longer, but the work is so closely related to his fashion designs that it’s hard to imagine him straying far from that approach.

It’s also hard, when looking at The Stephen Sprouse Book, not to feel that Sprouse’s art and designs speak not just to the 1980’s but to something still alive in our culture today. From the glitziness of the Beijing Olympics to the extravaganzas of contemporary rock and country music concerts, we live in a Day-Glo world. The book is in some ways a historical document visiting our pop culture past. In other ways, it’s a mirror reflecting something about ourselves and where we are now. Either way, Roger and Mauricio Padilha have put together a remarkable book about a remarkable individual who broke the mold with a visual style that looks like it isn’t about to disappear any time soon.

Lester Strong is a special projects editor for A&U magazine and a regular contributor to OUT magazine.