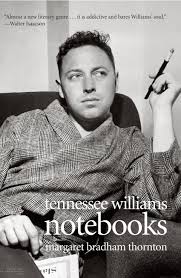

Notebooks

Notebooks

by Tennessee Williams

Margaret Bradham Thornton, editor

Yale University Press, 828 pages, $40

ON AUGUST 2, 1936, at the age of 25, Thomas Lanier Williams confided to his notebook: “I wish I loved somebody very dearly besides myself—.” Thus, early on, Tennessee Williams set the tone of this remarkable, disturbing, often repellent and unsavory record of his life. What strikes a reader here is the extraordinary self-absorption as well as the self-awareness of the remark. There’s nothing I can say about the character of Williams that emerges from the 45 years covered in the Notebooks that isn’t already admitted by the author himself: “I am certainly a damned pessimist or a nervous wreck or something”; “spirits still low but no crisis”; “tired old maid”; “[I am] my only ardent lover (though a spiteful and cruel one)”; “I am not exactly the world’s most tranquil person.”

He was less likely to accept the label of hypochondriac, though that characteristic is omnipresent. It became a sort of badge of rebellion to refuse to accept each single doctor’s verdict—that there was nothing ever substantially wrong with his physical health. Bathetically, notwithstanding the strain on his heart from all his worrying about his heart, Williams would die by choking on the cap of an eye-drop bottle. The body throughout was as likely to dominate as the mind in Williams’ self-evaluation—and it is rarely comfortable or pretty: “(Just spat up some bloody mucous).”

The close relationship between aspects of Williams’ life, the short stories he wrote, and the slow, ceaseless process of turning these first into short plays, then full-length ones, has long been understood. What the Notebooks show is how bizarrely Williams moved between conscious and unconscious acceptance of the particularity of his dramatic themes. In his last decades, he becomes increasingly prone to quoting his own characters, rather than other writers or philosophers, to support his world view.

There are infrequent appearances by Williams’ favorite authors—perhaps surprisingly, D. H. Lawrence, James Joyce (“probably the greatest writer since Shakespeare”), and Hemingway. Few dramatists figure, except for three: Strindberg, whose symbolist dramas are a favorite; Chekhov, who’s an inspiration; and O’Neill, of whom Williams is strongly aware rather than in awe. He was remarkably uninterested, though, in the breadth of literary culture in general, and rather unperceptive about authors whose values he rejected, or thought he did, such as Proust. Williams managed only the first sentence of A la recherche, only to break off and note smugly: “How we might have ‘dished’ the world in that cork-lined room of yours.” It was all about him. He was prone to “discoveries” that must have been important for him but nobody else: Shakespeare was “no damn sissy.”

Williams, in fact, wasn’t too interested in culture per se. Carmen is the one opera he could bear, El Greco one of few artists he engaged with, and then only following Hemingway’s description of the mannerist as “king of the queers.” Despite great travels, Williams scarcely glanced at the world. Arriving in Basel, he wonders briefly if he’s in Switzerland or Germany (the former, of course, though Basel effectively borders France too), resolving the question with: “The people look like Krauts to me.” The only place he ever really warmed to was Barcelona (lots of everything available). Athens was a mistake, leavened only by the subsequent discovery that Istanbul was far worse.

Once fame arrived after World War II, there were fellow travelers of note, such as Christopher Isherwood, Gore Vidal, Truman Capote, and Carson McCullers. Williams, though, either through drink (frequent), drugs (constant), or simple self-absorption, did not generally bother in these private journals to sketch the characters of those he encountered; often, a single line would sum up an appearance. There is more on offer in his notoriously unreliable Memoirs (1975), just republished from New Directions (see Andrew Holleran’s review in the March-April 2007 issue of this journal).

The case of Isherwood is instructive, since the appearance of his diaries between 1997 and 2000, themselves informing Peter Parker’s rather acrid take on the transplanted English author, did much to revise our view of his character. Fairly or not, Isherwood struck this reader and others as petulant, self-interested, at times manipulative, and, most shockingly, rather boring on the (private) page. It is interesting that Williams wrote that Isherwood “seems strangely like me … only clearer, quieter, firmer. A better integrated man.” In his case, the Diaries have appeared with the consent of Isherwood’s executor and life partner, Don Bachardy. Williams’ estate likewise has sanctioned these Notebooks, and the effect upon the playwright’s personal reputation is likely to be detrimental. Williams often reflected in these pages upon their possible publication, finding great merit in them one minute and ridiculing their monotonous tantrums the next.

The first-class efforts undertaken by editor Margaret Bradham Thornton as literary sleuth certainly render the book of great interest to scholars and lay readers who want to know more about Williams. Yale has become pre-eminent in the publication of handsome, affordable books of authority. Here, Williams’ entries fall on the right-hand page, opposite Thornton’s myriad references to associated correspondence (some, but far from all, drawn from the two volumes of collected letters published by Norton in 2001 and 2004), biographical details of everyone cited (barring the most occasional hustlers), hundreds of photographs, reproductions of Williams’ theatrical drafts, poems, daubs, scribbles. You think: it is all here. Except: a great chunk of his career is unaccountably missing—1958 to ’79, the years of the most serious decline in his reputation as a dramatist. It’s not known whether Williams ceased keeping notebooks, or whether he lost or destroyed them. Rather than simply lose the serial flow, Thornton glosses those years appropriately until she and we are ready to face 1979 and the saddest last years.

It is all here. Yet a reader may feel cheated, ultimately. Was Williams as awful and catty as he seems in these entries? He noted at one point that “this is where I wish to record my less exuberant moments.” Fair enough. Even in group pictures, he seems animated, partyish, winning, in ways that simply do not come across in the Notebooks. Under the influence or not, Williams seems somehow unalive, unaware of how to make prose sing, or people breathe. Take: “I have taken a sleeping tablet and will read Ibsen.” The one, of course, prevents Williams making any worthwhile comment on the other. On page after page, so many pills! He notches up a fair few centuries of sexual conquests, too. Early on, these are only glancingly referred to, as in “the nightingales sang last night” or “ashes hauled.” Williams in his maturity, however, was more than willing to document cock size, roles, frequency, agility or lack thereof, and even, on occasion, his own impotence.

Awkward as it is to admit, the unpleasant adage about the inverse relationship between sexual repression and literary creativity would seem to be borne out in Williams’ case. Not that his great works were written in a context of erotic famine, but they were distillations of grievances, longings, and frustrations long past. Williams had more in common with Proust than he knew. Likewise—and this is the best thing to emerge from the Notebooks—Williams’ relentless industriousness, very much in spite of his temperamental neediness, is clearly fueled by his loneliness and sexual lack early on. As a young man of 26—and Williams was young for a long time—he wrote a “silly” class paper, “Comments on the Nature of Artists with a Few Specific References to the Case of Edgar Allen Poe,” which makes the following claim: “The number of artists that survive out of the number of potential artists is probably comparable to the number of vitalized sperms in an act of sexual conjugation: millions are ejaculated: one out of that number achieves the fertilization which is its object.”

Utopian or dystopian? The yet unpublished author longed to be that acclaimed, cherished, enduring single sperm. Fifty years later, a part of him still wanted it, as off-off-Broadway failures follow one another. But the dominant mood in “old” Williams was to settle for the consolations of sperm in the much more literal sense (“getting my gun off,” “sinking my shaft”: Williams remained terrified of sissy behavior or language, and resorted to Hemingway-like idioms). The chase, at least, was often thrilling to Williams, but for him (and for us) its constant repetition was dulling: “Tried novel position in bed. OK till I came, then awfully tiresome.” This is a revealing summary of Williams’ limited capacity to empathize, or reciprocate at all, sexually or otherwise.

Some of Williams’ desperations were more deeply grounded and remain striking: the acknowledgment of lobotomized sister Rose as the “living presence of truth and faith in my life”; the too poignant first encouraging (and apparently approving) reference to the operation: the doctors had, he wrote, “accomplished something quite amazing.” I defy anyone not to be moved by Williams’ many references to starving, having to move on for lack of money, begging, and the “desperate squalor” in which Noël Coward found him in Rome. Williams paid his dues more, and more often than most, and his genius took a hell of a long time to be revealed—first to himself and then to others. The more one remembers the brutal, censorious age in which Williams dared to stage his bright, outré sexuality, the more there is, perversely, a sense of bravery at least, as he gets turned out of one hotel after another for “entertaining,” or gets beaten up for importuning on the street, finding the damage to his face “incredibly tender and sad.” Even his “little pets”—the crabs—are considerable antagonists over whom Williams must triumph, if and when he could afford the cream to treat them. And then there is his loneliness. As Kenneth Tynan would profile Williams after a single meeting: “he longs for intimacy, but shrinks from its responsibilities.”

Most moving, I thought, was critic Walter Kerr’s apt summary in 1953 of how Williams would—not to be unkind—squander, or rather misplace, his dramatic genius. Of Camino Real Kerr wrote simply: “You’re heading toward the cerebral—don’t do it!” Williams would continue writing for another 28 years, but never to the same effect as in the handful of masterpieces he had completed at this point. By now, the Notebooks pay less and less attention to questions of dramatic structure or technique and more and more to lamenting Williams’ own tragedies, like the experience of getting on a plane “without a full bottle on me!”

There’s the odd editorial glitch or perverse emphasis. Surely the footnote “Prior to 1946, Italy had been governed by a monarchy” seriously misrepresents the reality. Paul Cadmus’ paintings did rather more than “hint at homosexual themes.” These are tiny quibbles in relation to Thornton’s huge labors, however. For all the horrors in this volume, and my deep ambivalence about its appearance at all, she and Williams have both been dedicated in the pursuit of a kind of truth.

Truman Capote may have fairly captured late Williams in the character of Wallace in his own late, disastrous roman à clef, Answered Prayers: “Here’s a dumpy little guy with a dramatic mind who, like one of his adrift heroines, seeks attention and sympathy by serving up half-believed lies to total strangers. Strangers because he has no friends, and he has no friends because the only people he pities are his own characters and himself.” But then again, look who’s talking. These Notebooks are—like so many of Williams’ bright, captivating barbiturates—fun for a moment, but eventually unsatisfying. In terms of literary history, they are transient; in terms of humanizing succor, mirthless.