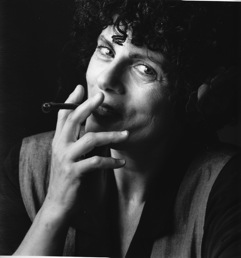

CRIME NOVELIST Patricia Highsmith is best known in the United States for two of her many tales, Strangers on a Train and The Talented Mr. Ripley, primarily because both were made into hit Hollywood movies. Born in Fort Worth, Texas, on February 21, 1921, and raised there and in New York City, she was far better known and acclaimed in Europe, where she lived a great deal of her professional life, and where she died in Locarno, Switzerland, on February 4, 1995, from cancer and aplastic anemia.

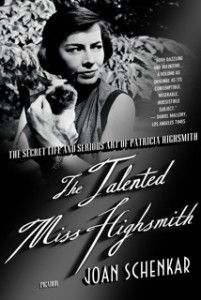

Recognition in the U.S. has been building, however, in large part because of The Talented Miss Highsmith, a remarkable biography written by New York- and Paris-based American writer Joan Schenkar and published in late 2009 by St. Martin’s Press (paperback edition published in January 2011 by Picador).

As any reader of Highsmith fiction knows, to enter her world is to receive a rather quick and thorough education in the psychology of criminal motives, twisted passions, and brutal mayhem. Highsmith is a master of suspense and violence, and for good reason: hers was an imagination steeped in criminal fantasies, which, fortunately for her and the people around her, were expressed in her work rather than in real life.

Highsmith was also lesbian, and she had a reputation for womanizing that encompassed a long list of failed romances in Europe and America, and one book with a lesbian theme, The Price of Salt. In writing The Talented Miss Highsmith, Joan Schenkar had unparalleled access to Highsmith’s literary and personal archives in Bern, Switzerland (the largest individual archive in the Swiss National Library), and carried out extensive interviews with friends, former lovers, professional colleagues, and members of her family both in the U.S. and Europe.

Joan Schenkar is an award-winning wrier and dramatist (see her website). In the following interview, conducted in person last October, she comments on the strange life and even stranger psychology of a novelist whose stories have enthralled millions of readers.

Lester Strong: Patricia Highsmith’s writing was for the most part about crimes and murder, and she certainly made her mark in the literary world, especially in Europe. To what part of our humanity do you think her stories speak?

Joan Schenkar: Humanity is not exactly a word I would use in relation to Patricia Highsmith. She always takes a walk on the dark side. Everything human was alien to her. She was born nine days after the dissolution of her parents’ marriage, which allowed her to say that she was legitimate but born out of wedlock. She came into a world that she didn’t care for, ever. From the age of twelve she detected that she was probably a boy in a girl’s body. Nothing about the way in which humans live their lives was easy for her. She was left-handed; they made her write with her right hand. The world didn’t fit any of her ideas about herself.

So, our humanity? I think she’s an inhumane writer in many respects. Her great, great virtue is her extremity. She went to the ends of her nerves to bring back the news, and it’s an extremely admirable thing. She’s a wonderful model for the way a writer should work. Her life is another matter. But life and art are usually incompatible. And she’s a marvelous paradigm for that.

LS: Highsmith, especially the older Highsmith, comes across as a very unsympathetic person in real life, yet I came away from your biography feeling compassion for her. Did you find anything sympathetic about her?

JS: It took me a long time to feel sympathetic towards Pat. Not because of her lifestyle, not because of the extremity of the dark feelings she examined. Because of her patent cruelty. I think life is very hard, and I think more than anything else the way in which she explored it and the way in which she behaved in life are very interesting things to think about. People love to speak about the humane virtues. I think she shows us a whole other wide world of the darker feelings, just as important as the lighter world of brighter feelings. She admitted to things in her diaries and journals that almost no one admits to. She was incredibly candid, and stood as both jury and judge on her own actions, many of which she felt extraordinary guilt for.

LS: Why do you think it’s important to explore our darker side?

JS: Look at the world we live in! One reason Highsmith is suddenly becoming more recognized in the country of her birth is that the world has finally caught up to Highsmith’s vision of it. She was an early detector of just about everything that’s wrong. In fact, she herself was a kind of museum of 20th-century American maladies.

LS: In the biography, you note Freud’s “sense of art as the locus of loss.” What was the locus of Highsmith’s loss that made her into an artist?

JS: The most important loss of her life, the one that sent her into mourning for life, was the loss of her mother [Mary Highsmith], for whom she retained to the end of her life deep feelings of hatred and love. Her mother—who was a career girl, really, a very early career girl—left her daughter with her own mother three weeks after she had her, with whom she had bad relations, in Fort Worth, Texas, and went off to Chicago to seek work as an illustrator. Although Highsmith’s happiest memories of her childhood were those of her strict, Puritan grandmother, it was the loss of her mother that she felt. She was raised more or less as a sister to her mother, and she grew up to court her, to light her cigarettes, to be sensitive to her moods.

Twenty years before she died, Highsmith cut off all connection with her mother, chiefly because her mother was in a nursing home, I think, and she just couldn’t bear the thought of an impotent Mary Highsmith. And when she cut off connections with her mother, her writing declined precipitously. The mother, whatever pain she caused, was an extraordinary inspiration for her. Sometimes your muse is the devil, and you’ve got to embrace it. And [Patricia Highsmith] did for a long time.

LS: What universe does a person inhabit, who states, as Highsmith did, that “life doesn’t make any sense without a crime in it?”

JS: To answer that you really have to go back to the books and to the notes she took for the books and to the many versions she wrote of each book. In every book except one, and that was the book she wrote about two women falling in love with each other [The Price of Salt], there is a murder. As I shuffled through her immense archives—if you measure them, they’d be 150 linear feet long, which was an awful lot of pages, every one of which I had to look at—she doesn’t feel right unless she’s committed a murder [in her writing]. It almost doesn’t matter who commits the murder and who the victim is. Often, through various versions of each novel, the victims and the murderers change. But once the murder is committed, she feels the novel is sufficient. The murder has satisfied her.

A Freudian explanation would be: “What a good release for all that rage.” And it was. She was physically not courageous in life. Her mother said she couldn’t bear the sight of a wound. She fainted at the sight of blood. She complained bitterly if [she didn’t feel well]. She was both a hypochondriac and someone who had many, many diseases, and she dreamed of murder all her life. So she used the work to do things that she could not do in life, which is a very good deployment of your artistic abilities.

LS: Aside from The Price of Salt, what part do you think her lesbianism played in her writing?

JS: She used every single important lover in her life as a kind of muse, each one a kind of inspired stand-in for her mother. And when she was in a happy, settled relationship—which occurred rarely, but it did occur—her writing dropped; she wrote her worst works. So these connections, which were as important to her as drugs are to any addict, were absolutely integral to her work.

Now it has to be said that she was horribly ashamed of being a lesbian. She felt immense guilt. And the one book she published about two women, The Price of Salt, she felt she had to publish under a pseudonym [Claire Morgan]. And when finally, in 1990, she was persuaded—the book was first published in 1952—to republish it under her own name, the title was changed [to Carol]. So it was as though some part of that book had to be disguised to make her happy. But it’s an extraordinary book, one of her five or six best, really. She didn’t commit a murder in it, but every single metaphor in that book carries murder with it. The love connections carry enormous hostility.

LS: You mentioned that she felt like a boy in a girl’s body. But in the biography, you also note: “The term ‘transgender’ hadn’t yet been invented. If it had, Pat wouldn’t have used it.” Why not?

JS: She didn’t like terms like that. It doesn’t suggest to me—and remember, I’m interpreting her now—the two distinct sides of her personality. “Transgender” means to cross genders. Highsmith stayed with two [genders], really, the boy within as well as the woman she was.

LS: Why did she find it more congenial to write about male heroes than about female heroes?

JS: Because she had what the French call “le mec dans la tête.” There was really a “guy” up in her head. In her reactions to women, and her scorn of the feminist movement, she was more chauvinist than most males were at that particular time, say in the 1970’s, which is when her revulsion for the feminist movement was at its height.

LS: There’s her misogyny. But considering the homoerotic attraction that exists between so many of her male hero-criminals and victims, it seems to me a good case could also be made for homophobia, since her stories don’t paint a very positive picture of male-male relationships.

JS: There’s only one book I can think of in which she actually portrayed men as lovers, the posthumously published Small g. And that is like a comic book collection of all her themes, not a very good book. She’s much better with the implied attraction. I think you could say that Highsmith was pretty much against everything. But if you set those works of hers in their time, they’re extraordinary. Strangers on a Train is amazing, and much more powerful for its implied homosexuality. Same thing for the first—which is the best—Ripley book [The Talented Mr. Ripley]. She never thought of Ripley as homosexual. He was weakly inclined that way, she thought. What Kenneth Burke, the great literary philosopher, would have called the “implicative character” of her work is much more interesting for being buried, subterranean.

LS: But terrible things happen between these couples, even if it’s just implied homosexuality.

JS: To whom don’t terrible things happen in a Highsmith book? She saw the world as hostile, love as a terrible trap, murder as a fairly natural instinct that doesn’t exactly bring release. The worlds she created are awful; they’re dreadful; they’re extreme. They’re certainly like nothing else in American literature. That’s why I find her so interesting. A year ago Norton published a collection of Highsmith works, two novels—Strangers on a Train and The Price of Salt—and thirteen short stories, which I edited and introduced. Also, I was just asked to do a chapter in The Cambridge Companion to American Literature about Highsmith, which means her exceptionally maverick work is now being admitted into the American canon. Her vision of the world is really like no other, and it’s a peculiarly American vision. It includes all the wayward feelings. She’s as American as rattlesnake venom, as I keep saying.

LS: Despite, or because of, her misogyny and homophobia, do her life and art have something of value to say to lesbians and gay men specifically in terms of being outside the mainstream?

JS: I would say she speaks directly to anyone who feels apart, alienated, not integrated into society. Let’s face it, she wrote maybe the most important lesbian novel—and she’d hate the use of the adjective “lesbian” here—written in America, which is The Price of Salt. She did it under great personal stress. If you read my book, you’ll see the extreme personal acts that drove her to [write it]. Nonetheless, she persevered, finished it, allowed herself to create a happy ending—and it’s tremendously convincing. I don’t think that lesbians and gays have to be separated from the artistic populace to understand that. [But] I would say that her works would speak to them more than perhaps anyone else because of the extreme states of feeling she explored. That’s very important for anyone who has been marginalized.

LS: Anything you’d like to comment on that I haven’t asked about?

JS: There is one thing I’d like to say about the fine art of biography. Because Highsmith was such an unusual character and lived her life in such a chaotic and nonchronological way—even though she obsessively notated her life chronologically—I had to invent a whole new form in biography to cradle her life and encompass her work. And so I’ve written a book organized according to her obsessions (though I included a forty-page chronology in one of the appendices for those who are made nervous by a nonchronological biography). I think she really put me on my mettle. She made me be as creative as I could be. So hats off to Highsmith.

Lester Strong is special projects editor of A&u magazine and a frequent contributor to The GLReview.