The History Boys

The History Boys

Written by Alan Bennett, from his play

Directed by Nicholas Hytner

WHEN AMERICAN Film-makers include gay characters in their films, they tend to focus on them as problematic—the problems of coming out; the heady, tragic problems of finding a boyfriend; family problems; and on and on. For films that incorporate well-rounded gay characters but aren’t about the supposed problems posed by gayness, it’s usually necessary to look to the U.K. or the Continent. Nicholas Hytner’s The History Boys, the film adaptation of Alan Bennett’s Olivier- and Tony-Award winning play, is the latest of these, and while it’s far from perfect, it offers a great deal of pleasure.

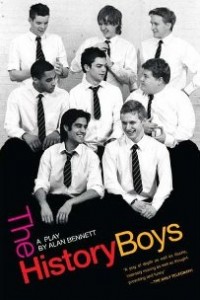

Hytner, who also directed both the West End (National Theatre) and Broadway productions, has retained his entire stage cast for the movie, with mixed results. Many of the intimate scenes are quite effective. Most of the ensemble set-pieces, on the other hand, have a dull, over-rehearsed feel; it’s not easy to escape the feeling that the actors are reciting rather than acting. This gives the film a wildly uneven texture.

Richard Griffiths, one of the most delectable character actors around, plays Hector, a teacher at a boys’ school in Sheffield. Hector prides himself on giving his boys a genuine love of literature, art, and music. His teaching style is eclectic and exhilarating, ranging from discussions of A. E. Housman to a re-creation of Now, Voyager and a Rodgers and Hart recital. He also gives the boys the occasional grope, something they put up with in a resigned way. (Hector has, we are told, an “unexpected wife” who doesn’t know what to make of him.)

Richard Griffiths, one of the most delectable character actors around, plays Hector, a teacher at a boys’ school in Sheffield. Hector prides himself on giving his boys a genuine love of literature, art, and music. His teaching style is eclectic and exhilarating, ranging from discussions of A. E. Housman to a re-creation of Now, Voyager and a Rodgers and Hart recital. He also gives the boys the occasional grope, something they put up with in a resigned way. (Hector has, we are told, an “unexpected wife” who doesn’t know what to make of him.)

When eight of the school’s boys earn test scores high enough to qualify them for admission to Oxford or Cambridge, Hector gets the job of preparing them for the interviews they’ll have to pass. Helping him are Mr. Irwin (Stephen Campbell Moore), a cynical young teacher who sees education as a game to be played and won, and the school’s only female teacher (Frances de la Tour), who harbors a resentment at male dominance. Clashes are inevitable.

The boys themselves are a by-the-numbers diverse group that includes a gay kid, a black kid, a jock, a Muslim, and an irresistibly handsome straight white boy. And they react to their teachers in expectably varied ways. Among them, the standout performers are Dominic Cooper as Dakin, the not-quite-straight hunk nearly everyone is in love with (including Mr. Irwin), and Sam Barnett as Posner, the gay boy who has a big crush on him.

This mixture produces a narrative that’s sometimes stagy and even leaden, at other times perfectly exciting. There’s a wonderful scene between Hector and young Posner, for instance, that is nominally a discussion of Thomas Hardy’s “Drummer Hodge” but is pretty clearly about something else. These two gay men, one middle-aged and closeted, one young and yearning, have something on their minds besides poetry, yet neither quite knows how to say so. It’s an extraordinary sequence, a triumph of sharp, perceptive writing and excellent acting with a carefully controlled subtext. In other hands it could easily have proved embarrassing. (Both Hytner and Bennett are openly gay, which could help explain the authenticity of the scene.)

But for every moment like that—and there are quite a few of them—there are those static, stagebound, over-rehearsed ensemble scenes. It’s difficult to fault either the script, the cast, or the direction in any specific way, yet it seems inescapable that someone not connected to the stage production should have been brought in to help release it from its theatrical roots.

This is definitely a film worth seeing, despite its shortcomings. How often do we get a movie that’s not “about being gay” in which most of the principal characters are gay? Where the gay figures have more on their minds than sex and/or romance? Where they display lively minds and deep intellectual passion? That alone makes this a worthwhile film. Add wonderfully intelligent writing and some of the best acting in recent memory, and The History Boys is a movie not to be missed.

John Michael Curlovich is the author of The Blood of Kings (2004) and Blood Prophet (2006), both published by Alyson.