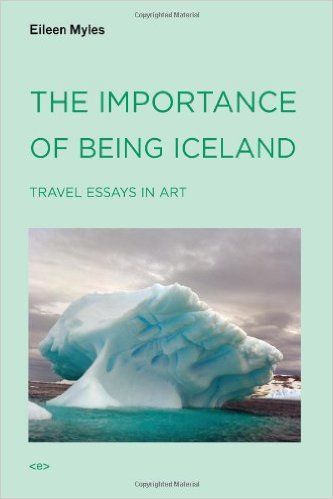

The Importance of Being Iceland: Travel Essays in Art

The Importance of Being Iceland: Travel Essays in Art

by Eileen Myles

Semiotext(e). 365 pages, $17.95

IN THE OPENING essay of The Importance of Being Iceland: Travel Essays in Art, Eileen Myles neatly summarizes her career as a writer: “I’m a poet and a novelist, one-time college professor, among other things. Generally as many things as possible.” It is that spirit of openness—the willingness to consider what’s surrounding her at any moment, and its potential for being absorbed into her own writing—that shapes Myles’ visceral explorations of other artists’ works in this book of art criticism. During an extraordinary interview with Daniel Day-Lewis, Myles comments in response to his question about her own artistic process: “I started writing poems in my twenties, and it got to be how I made a map of the world.” Myles’ reflections on the art that’s been produced by a wide array of international art scenes—from America to Iceland to Russia—also provide a kind of æsthetic map of her own creative writing. Like her poems, her critical essays often swerve from impulsive to insightful, from hilarious to moving.

The scope of Myles’ book is itself a formidable demonstration of her range of interests and her constantly shifting attention inside “the pinball machine of our time.” Covering 25 years of her criticism, from 1983 to 2008, her essays encompass painting, drawing, collage, sculpture, architecture, music, dance, photography, mainstream and experimental film, pornography, environmental art, found art, installations, performance pieces, journalism, literature, poetry readings, political events, social gatherings, celebrity culture, and the actual artist as a piece of “self-made” art. How does one begin to encapsulate such an exhaustive inventory? Naturally for Myles, the best approach to her essays is the poetic method of association: “Every artist, every writer, every movie star wants to enter reality deeper and bring everyone with them—have a teevee show, a magazine, or open a store. Everyone wants to start a club somehow, have a world, say come on in. You’re home. Inside my head.”

Once we’re inside Myles’ head, the wildest and most liberating connections begin to become clear. Her aerial views of Robert Smithson’s spiraling stone jetties, as described in her review of his selected writings, converge with the Fourth of July fireworks that she watches from an airplane on a cross-country flight, described in one of her many journal entries (“Teeny dots of light everywhere you could see … I saw it rise and open like a radiant flower”).

Throughout these essays, Myles possesses a direct engagement with each work at the level of emotion, a quality that many art critics today too often lack. It’s what the late critic Susan Sontag called an “an erotics of art.” Even in Myles’ interview with Daniel Day-Lewis (who’s the son of the celebrated English poet Cecil Day-Lewis), she finds enough emotional common ground with the actor to risk asking him point-blank: “Do you believe in god?” Her interview with African-American poet and playwright Ntozake Shange is noticeably less relaxed, but Myles still manages to dispel the tension skillfully enough to elicit a lucid description of the artist’s aim in society: “To keep our sensibilities alive so we aren’t numbed by our struggles to survive.”

Myles’ essays about traveling around the globe to meet with other artists are among her most effective pieces, mainly because of how freshly she grapples with the strangeness of these new and distant places and people. She visits St. Petersburg, Russia, for a personal tour of its gay bars and art galleries with the renowned writer–photographer Slava Mogutin, one of that country’s only openly gay journalists, who introduces her to an entire underground network of queer Russian artists. Myles writes of Mogutin: “He’s an excellent source on ‘a gay life,’ and especially the way in which a famous gay person is ultimately reduced to any gay person by a homophobic culture,” a fate that Myles claims a gay American icon like Allen Ginsberg avoided by being “more of a star than a homosexual,” one whose “great triumph was that you forgot he was gay.”

Myles becomes equally immersed when hiking through the rain-swept wilderness of Iceland, or when living for a week in a specially made cardboard box on the streets of New York City, or taking in a Björk concert at the Red Rocks amphitheater in Colorado, or marveling at the Perseid meteor shower among assorted desert-dwellers under the stars in Joshua Tree, or driving through the flat, rural mid-section of the U.S. with an itinerant band of lesbian writers and performance artists known collectively as Sister Spit. And Myles is at home, too, in various styles of writing, perhaps most of all in her recent blog posts that appear at the end of the book. Rarely more than a paragraph long, these prose poems allow her to keep up with the world at its own frenzied pace, while also freeing her writing to move at the speed of thought. She describes her arrival in Las Vegas as “like being inside a tattoo,” David Sedaris’ books as “touristy,” and the representation of light in an Edward Hopper painting as “not god, but simply our friend.”

“Part of the poet’s job when she steps up to the mike,” writes Myles, “is to make the unusual usual.” Likewise, her critical essays render the world and its art as “usual” and tangible, yet Myles always makes certain that her own perspective remains just unusual enough.

Jason Roush, author of After Hours, Breezeway

, and Crosstown

, teaches at Emerson College.