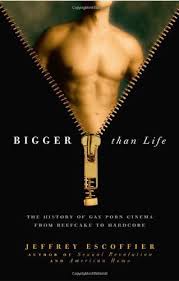

Bigger Than Life: The History of Gay Porn Cinema from Beefcake to Hardcore

Bigger Than Life: The History of Gay Porn Cinema from Beefcake to Hardcore

by Jeffrey Escoffier

Running Press Books

367 pages, $24.95

THIS BOOK is surprising in part because its author is Jeffrey Escoffier, a serious and reputable gay social theorist who is now venturing into a subject area that many people might consider frivolous, if not unworthy of sober analysis. In fact, as his history of gay pornography amply demonstrates, this genre is rather more serious than we probably like to admit. Bigger than Life reads like a work of journalism about the rise and development of a hugely successful industry that feeds the fantasies of gay men, whose growth spurts and mutations over time have aligned with social and technological forces.

The history of gay porn is sufficiently long and complex, and the personalities working on both sides of the camera sufficiently fascinating—as well as banal, and numerous—that Escoffier had the daunting task of corralling and taming an enormous amount of information. His extensive research encompasses assiduous academic scholarship along with interviews with porn producers and actors that he conducted himself, plus others that appeared in magazines like Manshots, HX, Frontiers, and Blueboy.

Escoffier guides us from the beefcake magazines of the 1950’s, which in their time, as one observer noted, “virtually were gay culture,” to that brief historical moment in the 60’s when Jack Smith, Kenneth Anger, and Andy Warhol created cult gay films—Flaming Creatures, Scorpio Rising, and  Blow Job, respectively—which took underground gay and camp sensibilities into hip bohemia’s independent art cinema. As official censorship began to crumble, gay and straight pornographic films found their way into foundering movie theaters that raked in cold cash by showing such fare as Wakefield Poole’s Boys in the Sand (1971) on the gay side and Deep Throat (1972) on the straight.

Blow Job, respectively—which took underground gay and camp sensibilities into hip bohemia’s independent art cinema. As official censorship began to crumble, gay and straight pornographic films found their way into foundering movie theaters that raked in cold cash by showing such fare as Wakefield Poole’s Boys in the Sand (1971) on the gay side and Deep Throat (1972) on the straight.

Bigger than Life tracks early pioneers like Fred Halsted, whose L.A. Plays Itself, which Halsted considered autobiographical, would eventually make it into the permanent film collection of the Museum of Modern Art. But the art cinema aspect of such early homoerotica moved relatively quickly into a more commercial mode as producers like Monroe Beehler formed Jaguar Productions “to produce gay pornographic feature films for theatrical release.” Beehler’s story lines would provide the “alibi” for hardcore porn to “escape being classified as obscene” in accord with the Supreme Court’s Miller v. California decision of 1973, which applied this label to works that lacked any “serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.”

Jaguar would nurture a number of aspiring hardcore filmmakers, among them Scott Masters (a.k.a. Robert Walters), John Travis, John Summers, and William Higgins. Travis and Masters would eventually found Studio 2000. Travis would also make the career of a young man from Illinois named Charles Casper Peyton who had an impressive dick and had worked on an oil rig in Texas and stripped at a Chippendale’s soon after turning nineteen. We know him as Jeff Stryker. From Travis’ image–building campaign, including photos and interviews in a new generation of beefcake magazines such as Inches, Torso, and Stallion, Stryker would emerge as one of the rare long-lasting porn careers that made the crossover between gay and straight, and exceeded the renown of such earlier stars as Casey Donovan and Al Parker.

As the book’s chronological narrative proceeds, the numerous personalities on the producing and directing side of the industry, and the wealth of film titles, grow increasingly difficult to keep straight, no pun intended, but Escoffier does a yeoman’s job of organizing his material. Notable careers that he follows are those of John Rutherford, Steven Scarborough, and Chi Chi LaRue. Only the latter emerges as a distinct personality, no doubt because she/he is truly bigger than life. Notable for being the most prolific of gay porn directors, Larry Paciotti goes by the name of his large drag queen persona and has also directed straight porn; he does not do his work en travestie. More than once, Escoffier emphasizes LaRue’s silent–screen directing approach, which includes shouting out instructions to his performers like “Go down on him!” or supplying loud, encouraging commentary like “Yeah, that’s fucking hot! Harder, harder.” As Escoffier explains, “Although some performers are uncomfortable with LaRue’s method, most find it valuable. The biggest problems … occur in post-production when the sound editor must … meticulously strip LaRue’s voice from the recorded sound track.”

The ability of gay porn to help men get in touch with their fantasy life and, in a more practical sense, to function as a how-to guide became acutely important as AIDS ravaged the community. The politics of safer sex played out differently in the gay and straight porn industries, although viewing porn as a means of safe sex was far more reliable than making it. This is a particularly bracing story within the larger story of Bigger than Life. A good many gay porn performers in the early days were whistling in the dark before condoms became de rigueur, while the straight industry ultimately regulated itself through HIV testing without condom use. Escoffier remains a remarkably neutral voice in chronicling this period of the industry’s expansion, but his reserved testimony on the individual losses in the industry—directors like Christopher Rage, performers like Al Parker and Joe Simmons, one of the first black stars—speaks for itself.

In the mid and late stages of the book, we’re introduced to the increasingly normalized character of pornography in our lives as “gay-for-pay” becomes just another career option. Of course, Jeff Stryker’s porn image was built around hyper-masculinity, which confirms how much the fantasy life of gay men has always been hung up on stereotypical tropes of manliness. But why settle for “actors”? Dirk Yates has been remarkably successful with his amateur interviews of clueless young Marines, some of whom prove surprisingly willing to engage in anal sex.

I do wish Bigger than Life had slowed down for long enough to address several equally fraught topics, such as the radical feminist critique of pornography by women like Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon, and the relative racial segregation of gay pornography, despite the success of a 1990’s figure like Matthew Rush. But Escoffier seems to have had more than enough to handle, as it were, to make him run the very kinds of theoretical minefields that we have come to expect him to navigate.

Allen Ellenzweig is the author of The Homoerotic Photograph(1992) and a frequent contributor to this journal.