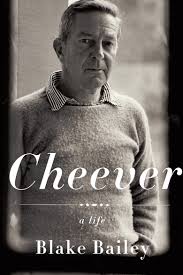

Cheever: A Life

Cheever: A Life

by Blake Bailey

Alfred A. Knopf. 770 pages, $35.

JOHN CHEEVER, who died in 1982, has a place in the American literary canon, primarily for the brilliant short stories he wrote from the 1940’s to the 1970’s. References to homosexuality appear sporadically throughout Cheever’s work, and a love affair between two men is at the core of his final major novel, 1977’s Falconer. Like many 20th-century writers whose lives have been thoroughly documented in journals, interviews, medical records, and reports by those who knew him, Cheever cannot escape his own biography. The publication of The Journals of John Cheever in 1991 revealed his homosexual propensities. Now Blake Bailey’s Cheever: A Life displays in painful detail how tormented Cheever was by his sexuality throughout his life.

The best literary biographies, such as Ted Morgan’s life of Somerset Maugham and P. N. Furbank’s treatment of E. M. Forster, handle their subjects with respect without ignoring their flaws, and examine their lives in the context of the world in which they lived. By this standard, Blake Bailey’s life of John Cheever falls short. It contains too much information on its subject without providing enough perspective. Bailey had access to Cheever’s private journals, which run to over 4,000 pages, and he quotes from them extensively. In these journals Cheever does not spare himself or others. We cringe when we read some passages, especially those about his sexual encounters. Bailey takes much of what he wrote at face value, whereas Cheever’s self-awareness was often clouded by sexual confusion, alcoholism, and depression. What emerges from the journals is a mean, boring, pathetic drunk, and this long book is no pleasure to read. Cheever often said that he wrote to make sense of life. Would that Blake Bailey had been able to make more sense of Cheever’s life. Cheever was born in 1912, the second of two sons. His older brother Fred was athletic and popular. John was short and sickly, a loner who had by his own admission an “effeminate wing.” He felt rejected by his father and brother, neither of whom would teach him how to be a man, and dominated by his strict Christian Scientist mother. He internalized the homophobia rampant in his family and the world around him, compensating for what he considered shameful impulses by adopting the gruff “red-blooded” manner of the men he admired and repressing for decades his sexual attraction to other men. Bailey clearly doesn’t like the persona Cheever created to make his way in the world, probably because he knows it will cause his subject and others so much pain in his later years. Still, this biography would have been stronger had he made a greater effort to understand what it must have been like for the young Cheever, born into a world of rigid social and sexual norms, to doubt the legitimacy of his manhood and go through life feeling like an impostor. Bailey is more successful in placing Cheever in the other formative context of his early life, the Great Depression. Cheever’s father, a shoe salesman, achieved some prosperity but lost his livelihood by 1930 and spent the rest of his life out of work, a disappointed man. Much to Cheever’s chagrin, his mother supported the family by opening a gift shop. Having a parent who had gone into shop-keeping shamed Cheever as much as did his secret sexual impulses. Cheever would later create a personal legend about his illustrious New England ancestors. Although there were many prominent Cheevers in early American history, they came from a family that was related to John Cheever only in his imagination. The family was able to send Fred to Dartmouth for two years before the money ran out. John never got further than Thayer Academy, a local day school where his grades were poor and he didn’t fit in with his more prosperous classmates. But at Thayer some kind of miracle occurred. Cheever read widely, mostly following his own impulses: Thackeray, Dickens, George Eliot, Proust, Joyce, Hemingway. And he began to write, publishing his first story at age eighteen in The New Republic. It is about a young boy’s expulsion from prep school, which indeed had happened to the author several months earlier. Cheever had no further formal education and would support himself for the rest of his life by his writing. Cheever’s stories and novels are about disappointment, loneliness, and a longing for connection with the natural or human world; he often finds it easier to connect with light and with water than with other people. To appreciate the genius of Cheever’s prose we have only to compare his writing to that of his brother. They came from the same milieu and Fred had the advantage of two years of college, but his writing as evidenced by passages from his letters is utterly prosaic. How did his self-taught brother become the master of such luminous words and cadences? Cheever lived a life of pretense—about his sexuality and his gentility. He discovered early on that words were the way to beguile readers, and maybe himself, into believing that his hoped-for world was possible. Blake Bailey’s biography demonstrates how close the connection was between Cheever’s life and his writing. It is a sad book, but if it sends readers back to this writer’s stories and novels, it will have done John Cheever a worthwhile service.